|

THEIR KINGDOM COME -- INSIDE THE SECRET WORLD OF OPUS DEI |

|

3. Enemies of the Cross

JOSE MARIA JULIAN MARIANO ESCRIVA Y ALBAS MADE HIS FIRST Communion on 23 April 1912, in the tiny church of San Bartolome. He had celebrated his tenth birthday three months before and since the age of seven had been attending the Piarist College, Barbastro's only secondary school. An old Piarist father, whom he later described as 'a good, simple and devout man', had prepared him for his Christian confirmation and taught him the formula for spiritual communion:

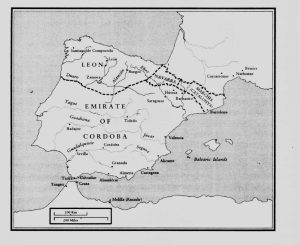

The words 'spirit and fervour of the Saints' held special meaning for him, for he and the other children of his class were being filled with the fervour of the great Spanish saints like Dominic Guzman and Ignatius of Loyola. All of us in varying degrees are creatures of the cultures into which we are born. Jose Maria Escriva particularly was marked as a son of Aragon. Raised in a deeply Catholic environment, the joys and prejudices of his traditionalist upbringing shone through in everything he did. The ancient trauma of Aragon's Moorish occupation helped shape his everyday perceptions. Moreover, the Crusading movement, so important in understanding certain of his motivations, was in a sense born at Barbastro. Aragon's early warriors were hard mountain men but their souls were softened by an intense admiration of Our Lady, whose cult was widespread on the south side of the Pyrenees. Escriva's often brusque temperament was also moderated by the extravagant regard he paid the Virgin Mary. Above all, Renaissance Spain's concerns for purity of blood and religion were stamped upon his heart. This did not mean that he was closed to other races or religions. But he placed his faith in the Holy Trinity and he believed that there was only one key to the gates of salvation. In exploring the world of Jose Maria Escriva's childhood, the Piarist College where he received his early schooling deserves special attention. Staffed by a dozen priests, it was not particularly large, with less than forty students, but it enjoyed considerable prestige. Jose Maria excelled at mathematics. Juventud, a magazine for and about the region's youth, reported that Master Escriva shared the first-year Bachillerato prize for arithmetic and geometry, and the following year he received special mention for religion and geography. [1] He developed an avid hunger for the legends of Spain's heroic past, a hunger which if anything grew stronger as he grew older. But young Escriva's appreciation of Spanish culture would remain selective. Though in the circumstances that might seem natural, one nevertheless is left to wonder what the Piarist Fathers taught their charges about Spain's early history. Did they explain, for example, that in 1064 Barbastro had been the site of a Muslim massacre despite a solemn papal promise of safe passage, all for the sake of greed? That would seem unlikely. Before the Moors came to Aragon, the Visigoths had been in the Iberian peninsula for 300 years, with their capital at Toledo. They ruled through a military aristocracy that became increasingly irrelevant as amongst themselves the Visigoth nobles could never agree about anything. To the south of the Visigoth kingdom, in North Africa, lay the westernmost outpost of the Byzantine Empire, the County of Ceuta and Tangier. In the early eighth century it was administered by Count Julian of Ceuta. He was nominally allied with Roderick, the Visigoth king of Spain. As Julian was cut off from Constantinople by the Moorish wave that spread across North Africa, he sent his daughter to be educated at Roderick's court. Roderick was struck by her beauty and attempted to court her. She rejected him. One night after a palace feast, Roderick raped her. When informed of his daughter's deflowering, Julian went to Musa, the Emir of Qairwan, capital of the Maghreb, as the Arabs called northernmost Africa, and proposed an alliance to invade the Visigoth kingdom. Musa wanted Julian to demonstrate the enterprise's viability by leading a preliminary incursion himself, which Julian did, enlisting a small Berber force to assist him. He ferried the Berbers across the straits to Tarifa. When they returned to Tangier at the end of the summer, their galleys were loaded to the gunwales with loot. A year later Musa followed up Julian's initial success by sending a 12,000-man expedition across the straits. The Moors landed this time farther to the east, in the lee of a rock they called Gebel Tariq -- Mountain of Tariq (and later known as Gibraltar) in honour of their general. The arrival of the Moors caught Roderick off guard and he hastened south with an army said to number 100,000. In 711, Tariq's outnumbered troops defeated Roderick in a battle along the Barbate River, and the Visigoth nation departed from history's stage. A 100,000 Moors now settled in Spain and the teaching of Islam spread. Within three years, Muslim armies had marched into France, and by 732 they had reached the banks of the Loire, where Charles Martel finally dealt them a shattering defeat. Though expelled from France, Muslim control of all but northernmost Spain remained intact. They established their capital at Cordoba. They set standards for tolerance unmatched by any society in Europe, except perhaps the eastern empire of Byzantium. Under the Emirate of Cordoba, Moorish Spain grew strong, and the cities of Cordoba, Seville, Malaga and Toledo were said to outshine any in western Europe. Towards the middle of the tenth century the emir of Cordoba invaded the last remaining Christian lands in northern Spain -- the Marches (Catalunya), Navarra and Leon -- and forced them to pay an annual tribute. But after his death in 961 the Christian princes stopped paying and in retaliation the emir's successor, Mohammed ibn Abi-Amir, surnamed Almanzor the Victorious, sacked the capital of Leon. A year later Almanzor plundered Santiago de Compostela -- an unpardonable outrage as Santiago, said to be the burial place of the Apostle James, was one of Christendom's most revered sites. At that time it ranked third as a place of pilgrimage, after Jerusalem and Rome. IBERIAN PENINSULA IN THE TENTH CENTURY As communications broke down during the Dark Ages, the Western Church became increasingly localized. Distant dioceses, remote from papal control, led their own existence, often submerging themselves in corruption and petty politics. According to Gibbon, by the tenth century the Church of Rome had reached her lowest ebb. [2] Reform, when it came, was through the monastic movement, of which the father was St. Benedict (c.480-c.550). He became the first to bring into popular use the phrase opus Dei. Benedict believed that personal sanctity could only be achieved by promoting God's work -- opus Dei -- while observing the monastic vows of obedience, celibacy and poverty, which he largely defined as the complete absence of personal possessions. [3] In the Middle Ages, the Benedictine Rule transformed monasteries that had become dens of narrow-mindedness into centres of learning and hospitality. It placed heavy responsibility on the abbot. He was selected through democratic process. Once installed in office, however, he was vested with near totalitarian authority. Abbots were not elected for life but for fixed terms. The danger that they might abuse their power was guarded against by making them accountable after their retirement from office. With Benedict's reforms, the monastic movement provided the impetus for renovation within the Church. Four hundred years after Benedict's death, the monks at Cluny, in central France, began to develop the pilgrimage as a political instrument. They noted that mass travel to the holy places -- what Opus Dei today calls 'religious tourism' -- could be used to reinforce Christian faith in lands threatened by Muslim domination. Thus the monks of Cluny began to promote pilgrimage as a Christianizing force. By the beginning of the eleventh century Cluny maintained the roads that led across Europe to the great Spanish shrines of Saragossa (still in Moorish hands) and Santiago de Compostela, and began to popularize organized pilgrimages to Jerusalem. Cluny now assumed a direct role in defending Spanish Christendom and preserving Christian access to the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. But transforming peaceful pilgrimage into a platform for launching military expeditions against Islam presented theological problems. Encouraging Christian princes to follow the Cross in a warlike enterprise infringed upon fundamental concepts of ethics and morality. But was a Christian not entitled to fight for his Creed? In 1063, Ramiro I of Aragon decided most definitely yes and began marshalling Christian forces at Graus, not far from Barbastro, for an attack on Emir Ahmed of Saragossa. Ramiro's first objective was Barbastro, held by a small garrison of Moorish troops. However, before the attack could be launched Ramiro was stabbed to death by a Muslim who had infiltrated the Christian camp. Europe was enraged. Pope Alexander II (1061-73) promised indulgence for all who fought for the Cross in Spain and set about raising an army to carry on Ramiro's work. The campaign against the emir of Saragossa preceded the First Crusade to the East by more than thirty years. The army of Sancho Ramirez, son of the murdered Ramiro I, was joined by knights from Aquitaine, Burgundy, Lombardy, Normandy and Tuscany. The campaign began and ended in 1064 with the siege of Barbastro, which lasted forty days. It would have gone on longer but was lifted in August when Alexander II promised that everyone in the town would be spared if they laid down their arms. Upon receiving a papal guarantee of safe passage, the outnumbered garrison surrendered. The Muslims were told to assemble outside the town gates with their possessions so that they could be escorted towards Saragossa. But when the Christian troops saw the extent of the wealth passing through their hands they slaughtered every man, woman and child, and made off with the booty. The butchery committed at Barbastro moved the Muslim princes throughout the rest of Spain to take revenge. Retaliation brought counter-retaliation. Intolerance bred counter-intolerance in a spiral of fundamentalist fury. By entrusting Aragon to Pope Alexander II's feudal care, Sancho Ramirez acquired the necessary military backing to broaden his attacks against the princes of Islam. The military expeditions of his brother, Alfonso VI of Castile, received the full-hearted approval of Pope Gregory VII, who became preoccupied with the idea of mounting a military Crusade to the East, but died before he had time to launch it. Gregory had been edging towards a doctrine that would encourage European knights to journey to the frontiers of Christendom to fight against Islam. As reward for taking the Cross they were allowed to keep whatever lands they seized by force of arms, which became an excuse for holy larceny on a grand scale, and they were promised spiritual benefits as well. But more significant, the papacy now took over direction of the Holy Wars, launching them as an extension of Vatican foreign policy, naming their commanders and placing a papal legate at their head. Five years after the massacre at Barbastro, almost 4,000 kilometres to the east the Seljuk Turks appeared on the fringes of Armenia and routed the Byzantine emperor Romanus IV at Manzikert. Asia Minor -- Christendom's most prosperous province -- fell to the invaders. The scale of the disaster at Manzikert was scarcely imaginable at the time. The Christian empire in the East was vastly more powerful than any other state. Its capital, Constantinople, sat astride the richest trade routes, making it the unrivalled financial and commercial metropolis of the world. It controlled the Mediterranean with an unmatched navy. And it possessed a dedicated and efficient civil service which administered territories from Calabria to the Caucasus. The source of Byzantium's wealth was in Asia Minor. It was rich in natural resources and its peasants were both free and hard-working. Its cities were populated by merchants and artisans who exported their goods to Constantinople, from where they were sold to the world at large. Asia Minor was where the bulk of the empire's taxes and the largest levies for its armies were raised. Separated from its economic backbone, Byzantium was doomed. But death would be another 400 years in coming. The Seljuks had embraced Islam before their appearance at Manzikert. They were followed by a horde of Turkoman nomads, travelling lightly armed, with their families and livestock, making for the upland prairies of which Asia Minor is well supplied. The Christians abandoned their villages and farms to be burnt by the invaders. Realizing no force opposed them, the Seljuks imposed their own laws and customs. They quickly overran the coastal cities of Smyrna and Ephesus and the more northerly centre of Nicaea. The sword of Islam severed Asia Minor from the Christian way. The change was abrupt. Only a few years before, the Christian Mediterranean had seemed a secure place, poised for years of peace. In spite of the wars against the infidel in Spain, Muslim and Christian in the eastern Mediterranean had learned to co-exist and trade with each other. At the same time the monks of Cluny had ushered in the great age of pilgrimage, sending thousands of European Christians to the Holy Land each year. But with the Seljuk eruption into Asia Minor, this religious traffic virtually dried up. More than anything else, the Seljuk victory at Manzikert hastened the coming of the Crusades. The Cluniacs had fired a Christian longing to visit the eastern holy places, and now debated ways of re-establishing the pilgrim traffic. They finally decided that a Crusader movement would be a just and moral means for countering Islam's rise and they explained their doctrine to Pope Urban II, himself a former Grand Prior of Cluny. [4] In 1095 Urban II was about to journey to France when he received a delegation from Alexius I, the new Byzantine emperor. Alexius was losing ground to the Seljuks and beseeched Urban to send him a force of Western knights. Urban did not reply immediately. As he travelled north to Clermont in France, where he had convened a Church council for that autumn, he struggled with the idea of calling a Holy War to open the way to Jerusalem. Finally, when the council assembled in November he proclaimed the First Crusade, which he portrayed as an armed pilgrimage to restore the Holy sites to Christendom's control. Urban died in 1099, two weeks after the investiture of Jerusalem by the Crusaders. Almost eight centuries later, in 1881, he was beatified. But Urban might not have been pleased had he lived long enough to learn how the Christian armies had sacked the Holy City. After breaching the walls, the Crusaders rushed through the streets, into houses and mosques, killing men, women and children alike. All through the first night the massacre continued. Those who sought sanctuary in the al-Aqsa Mosque on Temple Mount were slaughtered like sheep. When not a single Muslim or Jew was left to be slain the Crusaders offered thanks to God in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Some years later the Christian military orders were founded. The idea for a brotherhood that was both religious and military came from a penniless Burgundian knight who in 1118 decided to devote his life to protecting pilgrims. He and a friend took vows of celibacy and set out to win recruits. The same year that Alfonso I of Aragon reconquered Saragossa they persuaded King Baldwin of Jerusalem to give them a wing of the royal palace on Temple Mount as their headquarters. The Poor Knights of the Temple, as they became known, were backed by St. Bernard of Clairvaux, a Cistercian who preached the Second Crusade. [5] The Templars grew into a cohesive military force and won great fame through their exploits. They had their own clergy, exempt from the jurisdiction of diocesan bishops, owing obedience only to the Templar Grand Master, who in turn reported to the Pope. The Templars participated in most of the great Crusader battles. But their rashness led to a disastrous defeat. In 1187 a Christian army under King Guy de Lusignan and Grand Master Gerard de Ridford was trapped by the Muslim leader Salah al-Din (Saladin) in Galilee. The King and Grand Master were spared, but all Templar knights who survived the battle were beheaded. Three months later, after only eighty-eight years in Christian hands, Jerusalem fell to Saladin. Not a building was looted, not a person harmed. Upon payment of an exit tax, the city's Christian inhabitants were permitted to leave. They streamed slowly to the coast with their possessions, unmolested, in remarkable contrast to the fate of the Muslims at Barbastro. Opus Dei historians do not tell us what the young Escriva thought of these events. We do know, however, that he was an admirer of the Knights Templar. Several of their practices would be incorporated into Opus Dei's norms and customs when, later, they came to be set to paper. That the Templars almost took over as rulers of Aragon was undoubtedly known to him, since the Templar headquarters in Spain were situated at Monzon, a small town not far from Barbastro. The near cession of Aragon to the Templars came about in the twelfth century when Alfonso I died without issue and bequeathed the kingdom to the Knights Templar. Rather than accept the Templars as their masters, the nobles persuaded Alfonso's brother, Ramiro the Monk, to take the crown. As Ramiro III, the new king's first duty was to marry, which he did, and within the year he sired a daughter, Petronella. Having thus performed his national service in the matrimonial bed, the pious Ramiro wanted to return to monastic life. But the nobles insisted he wait at least until his infant daughter had reached an age when she could be respectably married. This occurred shortly after her second birthday; Petronella was given in marriage to Raymond Berengar IV of Barcelona, a warrior count in his forties. The nuptials were celebrated in Barbastro. Only then did Ramiro return to monastic life. Shortly afterwards, Catalunya was attached to the Kingdom of Aragon. As the new king of Aragon, Raymond Berengar compensated the Knights Templar by giving them the town of Monzon. There they turned a former Moorish fort into one of the most extensive military works in Spain. Master Escriva knew the fortifications well, having explored them on visits to his grandmother at nearby Fonz. The concept of celibate Christian warriors sworn to obedience and secrecy fired his imagination. After the fall of Jerusalem, only seven more Crusader campaigns were dignified with a numeric prefix, signifying that they enjoyed papal approbation. The Third Crusade (1189-92) was led by Richard I of England, Philip II of France and Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa. It resulted in a military fiasco but produced a five-year truce permitting unarmed pilgrims free access to the Holy Places. The Fourth Crusade (1202-04) was diverted to attack Byzantium for the benefit of Venice and was the most wicked. The Crusaders' looting, arson and murder that followed their capture of Constantinople horrified the world and once the rape was completed, they forgot about Jerusalem and proceeded to divide the Eastern empire among themselves. The disaster of the Fourth Crusade weakened the defences of Christendom. The land route from Europe to the Holy Land became totally impassable and no armed expedition from the West would ever again attempt the journey across Asia Minor. Three years later King Andrew of Hungary obtained Papal approval to redress the situation by leading a Fifth Crusade. The objective was Egypt, regarded as the brawn and bowels of Muslim strength. However King Andrew achieved little and returned home with his army in 1218, transferring command of the remaining forces to Cardinal Pelagius of Spain. Pelagius took Damietta in November 1219, but after an abortive attack on Cairo he was forced to negotiate a truce and withdrew. The Sixth Crusade (1228-29), led by Emperor Frederick II, produced the Treaty of Jaffa, which again gave the Christians access to Jerusalem. The Seventh Crusade (1248-54) resulted in Louis IX of France capturing Damietta for a second time, but another attempt to seize Cairo failed and the French monarch was taken prisoner. He was released after the French treasury paid a ransom of 800,000 gold pieces to the Sultan. Louis IX returned to North Africa in August 1270 at the head of the Eighth Crusade. But the endeavour was cut short when he died of the plague under the walls of Tunis. The Ninth and last true Crusade was led by Prince Edward of England. He landed at Acre on the Palestinian coast in May 1271 with a mere one thousand men. While drafting plans for a march into Galilee he was stabbed by a fanatical Muslim of the sect known as the Assassins and lay ill for several months before returning to England to become king. The Crusade as a militant Christian concept was by then debased. Once reserved for the fight against Islam, it had been co-opted for other papal designs. Spiritual rewards were promised to anyone willing to fight for Rome against whomever opposed papal policy, whether Greek, Albigensian or Turk. After the fall of Acre in 1291, the Templars moved to Cyprus. There they devoted themselves to finance, becoming the West's chief money-lenders. As bankers, the Templars were scrupulously honest. They understood the value of capital gains and were shrewd evaluators of risk. As with Opus Dei seven centuries later, they became a major financial corporation within a remarkably short time, amassing more wealth and influence than many states and any other Christian enterprise of its day. However, Philip IV of France plotted to bring the Templars under his control and to confiscate their assets. He waited until the Grand Master Jacques de Molay came to France on an official visit. During the night of 13 October 1307 he had de Molay and sixty of his knights arrested on trumped-up charges of treason, sexual perversion and devil worship. Pope Clement V acceded to French pressure and dissolved the Order. Philip had the Grand Master burnt at the stake, the traditional punishment for heretics. As the flames rose around him, de Molay damned King and Pope for betraying God's trust and he called upon them to meet him within the year before God to answer for their crime. Clement V died within the month. Philip followed seven months later. His disbanding of the Knights Templar proved another serious blow to Christendom's defences. In little more than a decade the Turks made their first appearance in Europe, while Jerusalem became totally closed to pilgrim traffic. After capturing Thrace and moving into the Balkans, in 1453 the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet reverted his attention to Constantinople and launched a final attack. During the night of 28 May, his Janissaries breached the Theodosian Walls and within hours the city was in Ottoman hands. After assuring that his troops committed no atrocities, nor desecrated a single monument, Mehmet converted Christendom's largest church, the Hagia Sofia, into a mosque and he changed the city's name to 'Stambool -- Istanbul. With the disbanding of the Templars, the only Christian thorn remaining in the Ottoman flank was the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, also known as the Knights Hospitaller. As a Military Order like the Templars, they were bound by vows of poverty, celibacy and obedience. The eight-pointed cross on their scarlet tunics was symbolic of the eight beatitudes. Its four arms represented the four virtues -- Prudence, Temperance, Fortitude and Justice. Like the Templars, they had escaped from Acre, going first to Cyprus before establishing their headquarters on Rhodes. More than two centuries later, Sultan Suliman the Magnificent drove them from the island. As compensation, King Charles I of Spain (later Emperor Charles V) gave them the island of Malta as their ultimate retreat. But there too they would be threatened by Suliman who wanted Malta as a stepping stone for his planned attack on Rome. Ottoman forces were by then at the gates of Vienna; the Sultan's beys ruled in Budapest and Belgrade, and in 1570 a Turkish force seized Cyprus. Pope Pius V requested Spain's help in forming a Holy League to defend Rome. The League raised a fleet under the command of Don John of Austria, illegitimate son of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Don John's previous assignment for the 'vice-regent of God', as his father was sometimes called, had been eliminating the Moors from the countryside around Granada, which he carried out with a guerra a fuego y a sangre (war by fire and blood), a sixteenth-century euphemism for ethnic purification. Now he went on to win the famous naval victory of Lepanto over the Turks. Had the Ottomans won the Battle of Lepanto they would have ruled supreme in the Mediterranean. The Christian victory saved Rome. Spain was then at the height of her power. A Spanish king was Holy Roman emperor and his armies were the Pope's enforcers. At home Spain was on the way to achieving purity of blood and faith. The process had begun well before Lepanto -- about the time Christopher Columbus set sail for the New World -- when Granada, Islam's last Andalusian stronghold, fell to the troops of Castile. Tomas de Torquemada, taking charge of the Inquisition, set in motion the machinery that would make Spain a uniquely Catholic country. First it was the turn of the Jews. The edict of expulsion gave them three months to convert or leave. A similar fate awaited the last of the Moors -- Don John, who had killed 60,000 Spanish Muslims at a cost to the state of 3 million ducats, had not done enough -- and in 1609, they too were forcibly expelled. Spain under Charles V counted a population of no more than 6 million. Even with treasure pouring in from the New World his subjects were over-burdened and over-taxed to pay for an imperial policy that made him the Pope's protector. Arming the Holy League for the Lepanto campaign had cost the Spanish treasury over 4 million ducats. By comparison, income from the South American mines was then estimated at only 2 million ducats a year. [6] Fortunately for the West, the Ottoman Empire now faltered; slowly its armies were rolled back, thanks in part to a split between the Shiite and Sunni branches of Islam that sapped the Muslim world of cohesion and strength. By then Spain had other enemies. Not only was she at war with France, but British freebooters were raiding her bullion fleets and disturbing overseas trade. Enforcing papal policy had exhausted the country. Charles V retired to a monastery, leaving his son, Philip II, a national debt of 20 million ducats and a war with France that was so costly it brought both countries to the edge of bankruptcy. In a final miscalculation, Philip moved the Invincible Armada against England. Its destruction raised the Spanish debt to 100 million ducats. Spain lost control of the seas and her long decline began. By the end of the sixteenth century, Spain's chronic inability to make ends meet -- servicing the national debt consumed two-thirds of the gross national product -- had ravaged her currency. Bullion imports from South America dried up. Deprived of fresh capital, agriculture and industry went into decline. Trade stagnated. With empty order books, shipyards closed and the merchant fleet, second to none at the time of Lepanto, shrank by three-quarters. By the time Jose Maria Escriva entered his final year at the Piarist College, social tensions in Spain were approaching breaking point. The origins of the unrest could be traced back to Charles V's reign. They had their roots in an imperial policy that had made the Spanish monarch God's vice-regent on earth, a policy that mortgaged the nation's wealth for generations thereafter. _______________ Notes: 1. Bernal, Op. cit., pp. 21-22. Also Vazquez de Prada, Op. cit., p. 55, citing Juventud Semanario Literario (Seccion de Gacetillas), ano 1, num. 4, del 13 de marzo de 1914. 2. Edward Gibbon, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Ch. 49. 3. Manin Scott, Medieval Europe, Longmans, 1964, p. 15. 4. Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades, Vol. 1, p. 84. 5. The Second Crusade, from 1147 to 1149, was led by King Louis VII of France and Emperor Conrad III. It was disbanded after an unsuccessful siege of Damascus. 6. Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, Fontana, London 1989, p. 59.

|