|

MOLEHUNT -- PICTURE GALLERY |

|

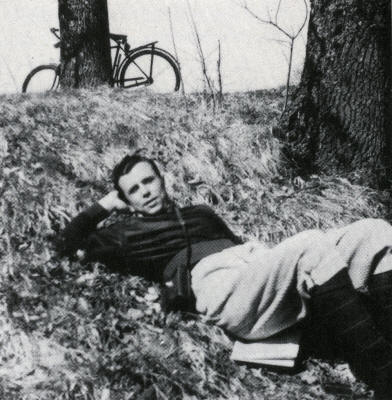

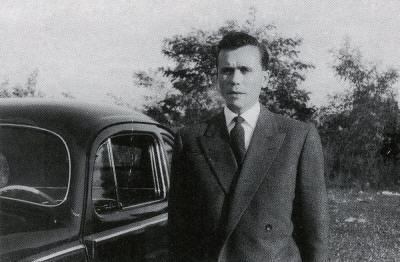

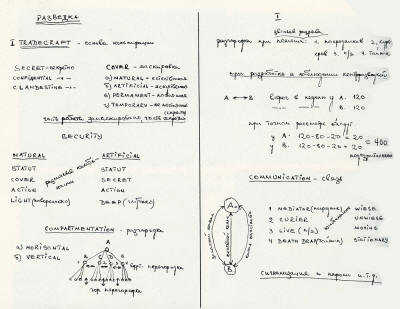

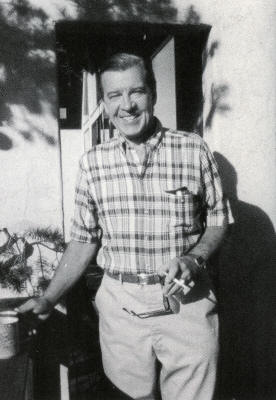

Orlov on an idyllic outing near Munich in 1947. He was already an agent of the CIA. Orlov in Berlin, 1953. The CIA trained Orlov in espionage tradecraft. Pictured are pages from notes in his handwriting in Russian and English. The CIA brought the Orlovs to America, where they opened an art gallery and picture-framing studio in Alexandria, Virginia. The FBI kept the gallery under surveillance for years, but never proved Orlov was a Soviet spy. After his death in 1982, his wife, Eleonore, continued to run the gallery.

George Goldberg became a suspect after Boris Belitsky, a top Radio Moscow correspondent whom he recruited for the CIA, turned out to be a double agent for the KGB. Innocent, but unaware that he had become a target of the mole hunters, Goldberg was puzzled that the CIA did not promote him. Goldberg, captured by the Nazis during World War II, was liberated by Soviet troops and pressed into service as their interpreter when the Russians and Americans linked up at the Elbe River in 1945. Goldberg, center, is the man in the wool cap.

|

|