|

THE MYTH OF SHANGRI-LA: TIBET, TRAVEL WRITING AND THE WESTERN CREATION OF SACRED LANDSCAPE |

|||||||

Chapter 6: Lost Horizons: From Sacred Place to Utopia (1904-59) Shortly after the end of World War II the famous Italian Tibetologist Giuseppe Tucci, and his party were invited to dinner by the Maharajah of Sikkim. At the reception, Maraini, the expedition's photographer, became fascinated by the Maharajah: I could not take my eyes off him as he tackled his peas; it was an exquisite, microscopic struggle; something between a game of chess and the infinite pains of the miniaturist; something between a secret rite, and a piece of court ceremonial. But now the struggle was over. The last pea, defeated and impaled on the fork, was raised to the royal lips, which opened delicately to receive it, as if about to give, or receive a kiss. [1] Without a doubt we are standing on the edge of a very different Tibet to the earlier ones of desperate landscapes, sweeping vistas or heroic struggles. Maraini was concerned with the small, intimate details, the poetic glance into corners of everyday life in Tibet. Not since Manning's mid-nineteenth-century account had so much careful attention been given to seemingly irrelevant details of Tibetan and Himalayan life. How the Maharajah of Sikkim ate his peas would have been of no interest whatsoever to Victorian travelers, concerned as they were with science, politics and adventure. Like Manning's obsession with Tibetan hats, Maraini's peas would have been deemed irrelevant and facile to an age thirsty for facts and overviews. But whereas Manning's perspective on Tibet was an exception in its time, Maraini's was typical of the new Tibet taking shape in the imagination of twentieth-century Westerners. The Tibet that emerged from the trauma of the 1904 expedition was indeed radically different to any that had existed previously. In 1918, with Britain victorious in the world war, the Dalai Lama telegraphed his congratulations to the king in London. Earlier in 1914, the Dalai Lama had offered a thousand soldiers to fight on the side of the Allies. He also ordered special religious services to be held for Britain's success in the war. These services continued throughout the conflict that raged thousands of miles away from Tibet. [2] The telegraph line to Gyantse that had been established in 1904 against the wishes of the Tibetan government was extended to Lhasa in 1921 in accordance with their demands. [3] By the 1940s the Dalai Lama had his own telephone and received regular news reports from the British Resident in Sikkim; [4] most of the wealthier people in Lhasa had their own radio sets; electricity was produced for the city by a diesel generator which was supervised in its turn by a young Tibetan engineer who had trained in England. Many of the young Tibetan officials had been educated in Darjeeling and were fluent in English. British and American books were to be found in their libraries, whilst Western magazines and newspapers were popular among the wealthy Tibetans in Lhasa. There was even a Tibetan-language newspaper printed in Kalimpong and subscribed to by most of the leading Lhasa families. [5] Some of the older Tibetans complained that wireless and electricity made winter in Lhasa stuffy! They need not have worried, for although the changes in Lhasa were startling they were extremely limited, scarcely touching the great mass of the population and their traditional way of life. These things were, however, harbingers of new attitudes, hopes and fears, among Tibet's leaders. They also revealed the diverse contact being established between the West and Tibet. Western goods began to fill the markets of Lhasa -- American corned beef, Australian butter, British whisky. As Heinrich Harrer reported in 1946: There is nothing one cannot buy, or at least order. One even finds the Elizabeth Arden specialties, and there is a keen demand for them. American overshoes, dating from the last war, are displayed between joints of Yak's meat and chunks of butter. You can order, too, sewing-machines, radio sets and gramophones and hunt up Bing Crosby's latest records for your next party. [6] The British assistant engineer responsible for extending the telegraph line from Gyantse to Lhasa in 1921 was impressed with the new, British-trained Tibetan army, complete with fife and drum band, bagpipes and bugles: It is quite inspiring to see the battalions fix bayonets, present arms to His Holiness to the tune of 'God Save the King', which the Tibetans had adopted as their national anthem, and march away with gorgeous yellow satin banners flying to the tune of 'The Girl I Left Behind Me'. [7] In 1921 the 13th Dalai Lama wrote: 'the British and Tibetans have become one family'. This remarkable leader also had his own garage to house a Baby Austin, -- numberplate Tibet 1 -- and an American Dodge. [8] He also agreed with the suggestions from Sir Charles Bell, the British Representative in Tibet and his personal friend, to send four Tibetan youths to school at Rugby in England and to open an English school at Lhasa. [9] In 1931 Robert Byron could reflect: Tibet, for us now, is no longer the 'land of mystery', a piece of dark brown on physical maps, gripped by an unholy hierarchy, and possessing no amenities of life beyond devil-dances and butter statues; but a physical, aesthetic, and human definition as implied by the words France or Germany. Henceforth it exists on the map of our intelligence as well as of our atlas. If, say the newspapers, this or that is happening in Tibet, this or that means something. In Terra del Fuego it does not. [10] Indeed, in 1936 Spencer Chapman could lie in bed at Lhasa and listen on his radio to the news from London and the chimes of Big Ben. [11] A Patchwork of Western Travelers Despite the renewed travel restrictions after 1904, the next fifty years witnessed the richest and widest possible range of travelers ever to enter the 'Forbidden Land'. Despite Byron's disclaimer to the contrary, Western fascination with occult Tibet increased both in popularity and intensity. At the same time as British officers were making several routine journeys a year from India to Gyantse and even on to Lhasa, other travelers were studying the profundities of Tibetan mysticism from lamas in Himalayan retreats. [12] The West was coming into intimate contact with a broad spectrum of Tibetan society. Westerners made friends with Tibetans ranging from the Dalai Lama, high-ranking officials, aristocrats and lamas to recluses and peasants. Nevertheless, it must be stressed that Western contact with the poorer reaches of Tibetan society were extremely limited and mainly confined to the exploits of travelers such as the French mystic-scholar Alexandra David-Neel who, disguised as a beggar woman, gained rare insight into this lowly aspect of Tibetan life. Similarly, refugees such as the Austrian Heinrich Harrer -- who, during the Second World War, escaped from a British internment camp in India -- were forced by necessity to contact ordinary Tibetans in order to survive in remote regions. One British global traveler, however, complained that it was impossible to get to know the ordinary Tibetans: In Greenland one could wander off and be perfectly happy with the Eskimos as long as one could speak the language. There one passed as an equal and lived, ate, hunted, and traveled just as they did ... Here it is fundamentally different. In this feudal country one is a Sahib. [13] Not only were Western travelers connecting with a bewildering range of Tibetan lifestyles, they were also finally emancipating themselves from the conventions of late-Victorian travel writing. As the quotation from Maraini at the beginning of this chapter shows, strict demands for 'facts' -- political, ethnographic, geographic -- were being complemented by other perspectives. Nowhere is this more clearly demonstrated than in the accounts of Robert Byron and Peter Fleming -- and also, of course, Fosco Maraini. At long last, humor found its way into Tibetan travel writing -- not humor at the Tibetans' expense, but a wry self-mocking of the travelers themselves. Byron showed his mastery of this style as he struggled to learn the language: G., to whom linguistic obstacles are unknown, insisted on our taking Tibetan lessons from a Sikhimese ... His long pigtail and twinkling elfin face, the spit of an autumn leaf, endeared him to us; while his sense of humor bore with equanimity G.'s suggestion that the whole language was an invention of his own, composed solely to annoy us. The inflection defeated us entirely. It seemed humanly impossible, when listening to him, to distinguish 'nga' (meaning 'I') from 'nga' (meaning 'drum'), or to distinguish either of these from 'nga' (meaning 'five'). 'Not "nga", he would instruct, 'but "nga"'; while we strained our ears in vain to catch the remotest difference between the two utterances. All we could do was to repeat the accursed syllable in bass, baritone, and alto, evoking in reward a pitying grin. [14] In addition to humor, accounts of personal experiences, whether of adventures or of the occult, were also in demand. David-Neel, for example, was to the Tibet of magic and mystery what Byron was to that of whimsy. Her encounter with the lung-gom-pa, one of the legendary lamas who by means of psychic training could move swiftly, running nonstop across vast distances of rugged landscape, has become famous and is a typical example of her heroic-occult prose: Towards the end of the afternoon, Yongden, our servants and I were riding leisurely across a wide tableland, when I noticed, far away in front of us, a moving black spot which my field-glasses showed to be a man. I felt astonished. Meetings are not frequent in that region, for the last ten days we had not seen a human being. Moreover, men on foot and alone do not, as a rule, wander in these immense solitudes. Who could the strange traveler be? She was warned not to stop the rapidly approaching lama, nor speak to him, for this would break his meditation and kill him. By that time he had nearly reached us; I could clearly see his perfectly calm impassive face and wide-open eyes with their gaze fixed on some invisible far-distant object situated somewhere high up in space. The man did not run. He seemed to lift himself from the ground, proceeding by leaps. It looked as if he had been endowed with the elasticity of a ball and rebounded each time his feet touched the ground. His steps had the regularity of a pendulum. He wore the usual monastic robe and toga, both rather ragged. His left hand gripped a fold of the toga and was half hidden under the cloth. The right held a phurba (magic dagger). His right arm moved slightly at each step as if leaning on a stick, just as though the phurba, whose pointed extremity was far above the ground, had touched it and were actually a support. My servants dismounted and bowed their heads to the ground as the lama passed before us, but he went his way apparently unaware of our presence. [15] During the post-World War I years Tibet also opened its doors to a limited number of tourists, although these were closely restricted to the trade route between India and the town of Gyantse. [16] Nevertheless, the tourist mentality could also be found in travelers who had the good fortune to journey deep into the country. In 1949 the Tibetan government, fearful of the rise of Chinese communism on its borders, invited two Americans, Lowell Thomas and his son Lowell Thomas Jnr, to visit Lhasa in order to bring the plight of Tibet to the notice of the American people Thomas Jnr wrote what has been called 'a slick, journalistic best-seller'. [17] Certainly his book bounces along from one cliche to the next for example, when given a rare opportunity to photograph the Dalai Lama, he could only exclaim: 'Now we are off for a real photographic spree!'. [18] Nevertheless, despite the great divergence of interests among Western travelers during the forty years from the end of World War I to the exile of the Dalai Lama in 1959, they were still woven into a fairly cohesive community. The British grip on access to Tibet funneled most expectant travelers along the same administrative routes. The lineage of British officers responsible for Tibetan affairs -- Bell, MacDonald, Richardson, Bailey, Weir, Williamson, Gould -- provided the backbone around which British contact with Tibet was organized. The French, too, had their own close network of Tibetophiles, especially at work in the eastern and southeastern corner of the country. Bacot, Guibaut, Migot and David-Neel jealously upheld the memory of previous French travelers and missionaries. [19] There was a certain amount of international rivalry among travelers in these regions. The British, for example, wanted to keep Mount Everest for themselves alone to climb, and did so successfully until 1952. [20] David-Neel was continually angry with them, holding them responsible for the closure of Tibet to legitimate travelers. [21] Guibaut was more subtle and, whilst eating a particularly tasteless meal, wryly remarked: 'French people have over-sensitive palates. On expeditions Anglo-Saxons have the advantage over them, because with them the need for nourishment comes before the desire to eat something which tastes pleasant.' [22] The Italians, too, were proud of their long tradition of Tibetan exploration. The medieval travelers Oderic of Pordenone and Marco Polo gave the first Western accounts of Tibet; Capuchins and Jesuits lived in Tibet during the eighteenth century -- Ippolito Desideri's account is particularly important. Italian exploration of Tibet and the Himalayas declined in the nineteenth century but resumed with some vigor in the twentieth, which saw journeys by the Duke of Abruzzi, Giuseppe Tucci, Fosco Maraini and others. [23] The Russians, of course, as we have seen, had a long-established tradition of Central Asian and Tibetan exploration. Finally, attention should also be drawn to the emerging line of American travelers in Tibet, beginning in the nineteenth century with Rockhill and including McGovern, Bernard, Tolstoy and Thomas in the twentieth. Other countries, such as Austria, had notable success in climbing the Himalayan peaks. Tibets Each of the previous chapters has described a different Tibet -- each one complete within itself yet built, like all great edifices, on the foundations of those that went before. All these Tibets also contained within them the seeds of their own demise, for they were not static but in process, constantly undergoing transformation. Earlier chapters have described this process: the genesis of a new Tibet in Western fantasy; the circumstances of its creation; its constituents; its significance for the West; its evolving perfection and its limitations; its decline and abandonment. Above all, these separate Tibets should not be treated as part of a historical evolution towards some ultimate realization about the empirical truth of Tibet. So, as the 1904 expedition led by Younghusband set in motion the end of one Tibet, it simultaneously began the production of the next. Of course, old themes and images continued, but as we shall see they formed new relationships, took on fresh significances: Tibet was still imagined as the northern rampart, the bulwark of India; [24] gold still exerted its fascination and was still invoked to explain possible Russian and Chinese -- albeit now communist -- interest in Tibet. Also, side by side with gold, uranium, a new mineral precious to the atomic age, began to fulfill a similar function. [25] Tibet still continued to be invoked in the same breath as Ancient Egypt. [26] Its culture, landscape and people were still constantly referred to, throughout the first half of the twentieth century, in terms of 'Alice Through the Looking Glass', 'Knights of the Round Table', 'Fairy Palaces', 'fairy-tale landscapes', or a 'Medieval World'. [27] If anything, such descriptions now became more commonplace, albeit slightly stereotyped and worn. However, Maraini still managed to breathe life into the medieval metaphor, developing it to its fullest expression: Tibetan life, viewed as a whole, is typically medieval. It is medieval in its social organization -- the predominance of the church and the nobility -- and its economic basis is agriculture and stock-breeding. It has the color and incredible superstition of France and Burgundy, the two most perfect examples of European medievalism; it has a medieval faith; a medieval vision of the universe as a tremendous drama in which terrestrial alternate with celestial events; a medieval hierarchy culminating in one man and then passing into the invisible and the metaphysical ...; medieval feasts and ceremonies, medieval filth and jewels, medieval professional story-tellers and tortures, tourneys and cavalcades, princesses and pilgrims, brigands and hermits, nobles and lepers; medieval renunciations, divine frenzies, minstrels and prophets. [28] What more could one possibly add? Maraini, consummate artist that he was, took an emaciated metaphor and gave it flesh. In his account Tibet was clearly forged as a link with memoria, with the long-lost ancestors of the Western imagination. It was, he wrote, 'perhaps the only civilization of another age to have survived intact into our own time'. He continued: Visiting Tibet ... means traveling in time as well as space. It means for a brief while living as a contemporary of Dante or Boccaccio, ... breathing the air of another age, and learning by direct experience how our ancestors of twenty or twenty-five generations ago thought, lived and loved. [29] There is a richness, if not a freshness, about this new Tibet, in which even the old themes seem to share. What Maraini did for medievalism, Byron did for light and color. Whilst he was, of course, not the only one to comment on these striking features, Byron said it all with an economy of phrase: Vanished for ever was the prussian-blue of Anglo-Himalaya and the Alps, that immanent, formless tint which oppresses half the mountains of the world. A new light was in the air, a liquid radlance ... here was a land where natural coloration, as we understood it, does not apply. [30] In Guibaut's account of his journey in South-Eastern Tibet, vivid colors, primitive vitality, archaic tradition and medievalism became synonymous: 'Outside in the courtyard the play of colors, under a brilliant sky, attains an African exuberance. The temple, with its slanting walls, assumes an Egyptian aspect ... The scene recalls the Middle Ages ... '. [31] Two centuries of complex fantasies about Tibet are here condensed into two sentences. What made all the difference was that this new Tibet was partly conscious of itself as a production, as a genre. There was, at least among the better writers, a sense of play, of dreaming the dream along. Byron, for example, wrote: 'This account must now enter upon the stage familiar to all readers of Tibetan travel-books, in which the desolation of the country overwhelms all other impressions. [32] No other Tibet was so aware of being supported by previous travelers' experiences. Migot, for example, actively sought out the spot where Dutreuil de Rhins was murdered nearly half a century before, and erected a memorial. He did the same for other French travelers in the region, paying them homage. [33] Captain Bailey, journeying through Assam to southeastern Tibet in order to explore the mysterious course of the Tsangpo river, followed the route taken by Pundit Kintup fifty years earlier. He similarly paid respect to the bravery and skill of his predecessor. Bailey went so far as to seek out the aged Indian explorer himself and ensure his reward and recognition -- just in time, for Kintup died shortly afterwards. [34] Again, Byron managed to convey succinctly the experience of this century-and-a-half's preparation when face to face with the actuality of Tibet. Turning a corner, I was confronted by a religious procession. It produced a curious feeling, almost fear, this first contact with persons, clothes, and observances of utter strangeness. For many years I had thought about Tibet, read about it, and gazed longingly at photographs of huge landscape and fantastic uniforms. Nonetheless, the reality came as a shock. [35] But he quickly recovered his poise and skillfully avoided any temptation to inflate the significance of the event. He continued: 'In the rear, borne in a palanquin, came a golden image preceded by a scowling fat monk. One might have been the Virgin, and the other a priest, in an Italian village.' The self-consciousness of this 'new' Tibet also revealed itself in a clash of stereotypes. Various authors would, from a supposedly superior position, gaze out and encapsulate the prevailing fantasies about Tibet, only then to dismiss them contemptuously as unreal. Creating and deflating all-encapsulating visions of Tibet was a common pastime among contemporary writers: For many Westerners Tibet is wrapped in an atmosphere of mystery. The 'Land of Snows' is for them the country of the unknown, the fantastic and the impossible. What superhuman powers have not been ascribed to the various kinds of lamas, magicians, sorcerers, necromancers and practitioners of the occult who inhabit those high tablelands, and whom both nature and their own deliberate purpose have so splendidly isolated from the rest of the world? And how readily are the strangest legends about them accepted as indisputable truths! In that country plants, animals and human beings seem to divert to their own purposes the best established laws of physics, chemistry, physiology and even plain common sense. [36] Such passages show how sophisticated the reflections on Tibet had become. Whilst David-Neel did her best to question and refine visions of the country such as the one above, Maraini wanted to throw them out altogether. 'In Europe,' he wrote mockingly, 'Tibet is always thought of as a strange country exclusively populated by mysterious sages, who pass their time performing incredible miracles in endless rocky wildernesses inhabited by rare blue poppies.' [37] Instead, Maraini wanted to emphasize the complexity of Tibet: its landscapes, culture and religion. He wanted to show a side of Tibetan life that 'was neither sublime, nor thaumaturgic, nor hieratic, but simply gay, pagan and innocent'. [38] The problem was that this newly acquired self-consciousness produced an arrogant struggle to establish the truth about Tibet, rather than encouraging a de-literalizing playfulness. Nevertheless, writer-travelers such as Maraini, Fleming and Byron used humor to its best advantage in their attempt to keep the imagination mobile within these grand, all-encompassing visions. Maraini, well aware of the leaden seriousness of occult fantasies about Tibet, brilliantly juxtaposed the profound with the trivial. For instance, Lobsang, a Tibetan friend, was telling him about various occult happenings: 'There are certain things that one must not know. Would you like some more tea? Even you strangers ought to have great respect for the gods, you can never tell what will happen.' Lobsang then went on to recount the story of Williamson, the British political officer who died at Lhasa in 1936, supposedly of a heart attack. According to the Tibetans, however, he died because he had photographed, without permission, some images of the wrathful gods: You may not believe it, but it's a fact known to everybody in Lhasa and Tibet ... Please help yourself to another biscuit, they're fresh. Sonam baked them; he's a good lad ... A few hours before Williamson died a perfectly black figure entered his room and snatched his soul ... Won't you have some more tea? [39] Byron adopted a slightly different approach. He took for granted the presence and pressure of Western expectations about fantastic, magical happenings in Tibet. On the way to Gyantse, he met a British officer. 'Personally, I like Tibet', the officer casually remarked. Having just followed Byron and his companions through a depressing and grueling winter landscape into Tibet, we, the readers, are naturally expecting some profound insight from this man who actually likes the place. What attracts him so much that he alone can shrug off the primitive conditions, the harsh environment? Is it the sublime landscapes, the occult mysteries, or perhaps just adventure? It is in fact none of these: 'The Indian troops at Gyantse are frightfully keen on hockey. I really get all the games I want. It's a bit lonely sometimes. But as I say, I get all the games I want.' [40] The demystification is complete; a fresh space has been created: the imagination is liberated from stereotyped structures. This is where the centre of gravity of the new Tibet is to be found: in these flashes of self-consciousness. It was a time when grand visions of Tibet were being both created and debunked. Sometimes this was all in terms of the search for the real Tibet; sometimes just for its own sake, for moments of imaginative play. Unlike the previous, nineteenth-century Tibet, neither a sustained desperate exploration of the landscape nor the urgent demands of imperial strategy dominated or brought coherence to this new creation. [41] Of course these two themes, so familiar to the West's relationship with Tibet, were still apparent, but they were now pushed -- literally geographically -- to the fringes. The two main, peripheral, regions where heroic feats of exploration occurred during this time were the southeast corner of Tibet and to the southwest of Lhasa, around Mount Everest. Danger was present in both: in the southeast corner from the local tribes, the Ngolos and the Mishmis; in the other region from the wild mountain landscape of Everest. In both, too, death was common. In the southeast corner, the French explorer Liotard and the French missionary Pere Nussbaum were murdered within ten days of each other in 1940. [42] The British also suffered in this region: Williamson, Gregorson, and thirty-seven others were massacred by the Abors on the border with Tibet in 1911. [43] The British made several desperate attempts to reach the summit of Mount Everest. Official expeditions, backed by an uneasy partnership between the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club (also, later, the Himalayan Club), set out in 1921, 1922, 1924, 1933, 1936, 1938 and finally, successfully, in 1953. Three British, eight Nepalese and four other Asians died in these attempts. In 1934 Maurice Wilson, an eccentric yet courageous and determined Briton, died 21,000 feet up Everest after a solo struggle between the power of religious faith and that of the mountain. The unsolved deaths of Mallory and Irvin in 1924, last seen only 800 feet below the summit, became legend. This event was to the history of Himalayan climbing what the deaths of four men on the Matterhorn in 1865 had been to the Alpine tradition. In Mallory, Everest found its true hero and martyr. [44] A third dangerous region was Tibet's northern frontier. After the collapse of the Chinese Empire. Sinkiang province was in a state of civil war for most of this period. The same applied to Tibet's eastern frontier although here the danger came more from bandits than from combatants in a civil war. Even the well-respected but aged Sven Hedin had considerable difficulty trying to pass through Sinkiang in 1926. Peter Fleming and the Swiss woman Ella Maillart, on their famous journey from China to India in 1935, gave graphic descriptions of the dangers along this northern route. [45] Leonard Clark's account is vivid in its portrayal of the violent anarchy along Tibet's eastern border, especially immediately after the Second World War. [46] In these accounts we still read of blanks on the map, of regions unseen by Europeans, of unsolved mysteries such as the Tsangpo Gorge, or the mountain in eastern Tibet that perhaps rivaled Everest. [47] But now it was not a whole country that was unknown, merely its high peaks, its odd corners -- 'This whole northeast quarter ... has been almost invariably circumvented by the old-time explorers'; [48] From now on every stride of our horses adds to our still very meagre balance-sheet of discoveries. From the earliest ages of mankind no traveler along these tracks has thought of marking out the land. We are going to submit this country to the discipline of geography. [49] Desperate attempts were still made, in disguise, to reach Lhasa -- Alexandra David-Neel in 1927, William McGovern in 1923. [50] Both succeeded. In 1913 Major John Noel also used disguise whilst making a clandestine and unofficial solo exploration of the routes to Everest. [51] There were also old-style, large-scale expeditions such as the one led by Nicolas Roerich, artist and mystic. Crossing immense tracts of Central Asia between 1924 and 1925, he nearly perished of cold and starvation when his journey across Tibet was halted by government officials." [52] In 1925 Edwin Schary, an American, struggled desperately across Tibet in search of the famed mahatmas. MacDonald, the British trade agent at Gyantse, described his arrival: 'One evening at dusk, a begrimed and filthily clad figure covered with festering sores crawled up to the main gate of the Gyantse Fort ... He was really in a terrible condition, verminous, ill-nourished, and really very ill.' [53] Fugitives, such as Harrer, Aufschnalter, Kopp and Ossendowski, produced remarkable stories of endurance across bleak uncharted regions of Tibet. [54] There was also the story of the American airmen who accidentally crash-landed in Tibet during the war while flying supplies to China over the notorious 'hump'. [55] As usual Byron, certainly no hero, managed to play with even this stereotypical aspect of Tibetan travel. His journey was by no means dangerous and followed a well-used trading route, stopping each night in government rest-houses. Nevertheless, his suffering was graphic: The morning, which came at last, was the crisis of the expedition. My own face, for which I had constructed a mask out of two handkerchiefs, had ceased to drip, and was now covered with yellow scabs, which adhered unpleasantly to the surface of the beard. But those of M. and G. had liquefied in the night, and they arrived in my room to breakfast, speechless with despondency. The cold was intense; the room was filled with the odor of yak-dung and lamp-smoke; my head was pounding; and I had whispered to myself, during the despair of dressing, that if -- if either of the others were to suggest an about-turn, I should not oppose him. To endure this pain for three more weeks would be merely the weak-mindedness of the strong. M., his face dripping, unshaven, and crinkling with nausea as it opened to receive a piece of tinned sausage, spoke the first reproach that I had ever known of him: 'Why have you brought us to this horrible place?' And then people say, but the Tibetans are so dirty, aren't they? They may be. But at least they preserve their faces. There can have been no one in the whole country so filthy, so utterly repulsive to look at, as ourselves by the time we arrived at Gyantse. [56] But these desperate moments, and the few heroic journeys, were almost leftovers from the fin de siecle, the golden age of Tibetan exploration. True, the public liked them, but after 1904 they no longer supplied the place of Tibet with its basic imaginative coherence. How Much Time is Left? 'There is little room to turn; one ill-judged movement may cause a fall to the bottom. This is Tibet's danger', wrote Marco Pallis in 1933. [57] Unlike the previous Tibets, which had a timeless permanence about them, in the twentieth century an all-pervading sense of loss was the leitmotiv of Western imagining. While the fin-de-siecle Tibet was edged with impermanence, now such fears were central. Marco Pallis was one of the most sophisticated and persistent critics of the changes taking place in Tibet and the Himalayan regions. [58] As the above quotation shows, he considered the situation urgent. For these Western travelers Tibet's imaginative status seemed threatened from four directions: tourism, globalism, the influx of Western ideas, and communism. The first three, as we have seen, were not new; but the fourth was most assuredly a child of the times. Amaury de Riencourt, who journeyed to Lhasa in 1947, wrote of 'almost the last independent civilization left in this shrinking world'. [59] There were fewer and fewer unmapped, unknown, untouched regions on the planet. Following in the wake of the explorers came the tourists. This, as we have seen, was an old fear, but whereas earlier it was thought they might contaminate Tibet, now it was feared tourism would eventually destroy it. 'The time is obviously near', wrote Guibaut whilst exploring the dangerous southeastern corner in 1940, 'when it will be possible to penetrate into Tibet by car or plane. Then Lama civilization will dissolve into tourism.' [60] In 1939 the American explorer Bernard wrote: 'Far-reaching changes, little short of cataclysmic, threaten the land of Tibet and Lhasa its capital.' [61] 'Would it any longer be possible', mused Thomas in 1949, 'for any nation, no matter how remote, no matter how isolated by high mountains, to shut itself off from the problems of the world, especially in this age of high speed, high-flying planes, radio short wave, and atomic energy.'? [62] It was this sense of time running out that characterized Western imagining. No sooner had the West found a place outside time and space than, like the freshly opened tombs at Mycenae, all began to crumble and turn to dust before their eyes. 'How much longer will it be able to endure?' cried Maraini. [63] 'A very ancient civilization, now condemned, is about to disappear', lamented Guibaut. [64] Was Tibetan civilization really so fragile, so lacking in resilience? Was the danger from Western ideas and tourism so great? Pallis apart, it did not seem as if any of those bemoaning the certainty of Tibet's fate had made anything but the most cursory study of the problem. What were these Westerners afraid of losing? As we have seen, previous generations had generally complained about Tibet's refusal to embrace technical ideas. Now this was reversed. While numerous ruling Tibetans were now cautiously enthusiastic about Western ideas, many Westerners were disillusioned with their own civilization. For example, in 1932 Robert Byron discussed the situation with Mary, a Tibetan friend: And then said Mary: 'I love Tibet. If only it had trains or motors, I think it would be the nicest country in the world'. 'But' , I answered, 'the monks don't like that sort of thing.' 'No', she sighed. 'Some people don't seem to want to be civilized.' I tried to sympathize with that sigh. The hardships of travel in Tibet can hardly be expected to appeal to those whose lifelong fate they are. But I could not. For once train or motors have been introduced, the Tibet that Mary loves will be Tibet no longer. [65] Here is the answer: it was not Byron's fate to have to live in Tibet. For him, as for many other Westerners, it was a symbol, and it was this symbol that was under threat. Those Westerners who actually lived in Tibet, like Heinrich Harrer, could not sweepingly dismiss all Western technology out of hand. 'I could not understand why the people of Tibet were so opposed to any form of progress', he wrote. 'The policy of the Government towards medicine is a dark chapter in the history of modern Tibet ... The whole power was in the hands of the monks, who criticized even government officials when they called in the English doctor.' [66] Tibet, of course, had never really been isolated -- had never been in deep freeze, or immune to outside influences. Indian and Chinese culture had thoroughly revolutionized the country in the past, and continued to influence it profoundly in modern times. In the nineteenth century, the idea of a static, unchanging Tibet had exactly dovetailed with British imperialism's role for it as a no-man's-land in the 'Great Game' with Russia. Now, in the first half of the twentieth, Tibet symbolized everything the West imagined it had itself lost. It was the last living link with its own past. As Pallis wrote, 'It is the last of the Great Traditions ...,' [67] Amaury de Riencourt spelt out the myth in full: 'In this most forbidden city on earth, the last representatives of doomed civilizations meet as they met a thousand years ago ... Here is still a living past.' [68] Tibet seemed to symbolize, too, a lost innocence. As the unknown regions of the planet succumbed to mapping, as the whole globe threatened to become culturally homogenized and as the West staggered, disillusioned, through two world wars into the dawning of the 'atomic age', it was perhaps not surprising that Tibet should be looked to as a place of sanctuary. No wonder many in the West wanted to freeze Tibet in time. It is also no surprise that the 1953 Everest expedition should have been called 'the last innocent adventure'. [69] Even the ironic Byron succumbed to the dream: 'I think once more of the blue sky and clear air of the plateau, of the wind and sun, of the sweeping ranges, and the chant of ploughman and thresher. Once more I see Tibet immune from Western ideas, and once more I wonder how long that immunity will last.' [70] Maraini, watching yet another colorful 'medieval' procession as a Tibetan noble journeyed across the countryside, sadly reflected: 'within a few decades these same people would be passing this way in motorcars, in horrible clothes not designed for them, and ... all I was seeing and admiring would be nothing but a memory'. [71] While one can readily sympathize with such sentiments, the desire to keep Tibet 'pure' and free from Western technology was simply the reverse side of the unquestioned nineteenth-century confidence in Western ideas of progress. Where were the beggars, the outcasts, the poor, in these modern accounts? Where was the chronic sickness, the harsh punishments, the corruption? Where the paradox? Thomas, for example, wrote: The lamas ... are convinced that they alone of all peoples are not slaves to the gadgets and whirring wheels of the industrial age. They want no part of it. To them the devices, doodads and super-yoyos -- the symbols of our western civilization -- are toys, of no real value. [72] Yet the Tibetans themselves were torn by contradictions. Smoking, playing mahjong and football, were banned in Lhasa. Wearing spectacles was disapproved of as un-Tibetan; no European clothes could be worn in the Summer Garden of the Dalai Lama; modern dances like the samba were frowned upon. Yet telephones, radios and cinema shows were welcomed, even encouraged. [73] It seemed as if Westerners wanted to simplify the actual, complex, contradictory situation in Tibet. The confusion of the Tibetans themselves was understandable. They were confronted by serious threats to their fragile independence. Could Tibet best survive by conservatively clinging to every detail of its tradition, or by selectively modernizing? [74] As the century progressed, it was gradually dawning on even the conservative Tibetan National Assembly 'that isolationism spelt a grave danger for the country'. [75] Even more than the disruptive influence of Western ideas, the spectre of communism threw its shadow across this Tibet. 'The peril is imminent', cried Lowell Thomas Jnr. in 1949. He had been specifically brought to Lhasa by the Tibetan government to let America know of what he called, the 'serious problem of defense against Asiatic Communism'. [76] Western travelers wrote of 'the Red Hurricane', 'the Marxist bulldozer', the 'fanatical Communist hordes'. [77] Whilst some were more circumspect and philosophical about communism, the underlying sentiment was generally the same. De Riencourt pleaded: Can the Western powers understand the terrifying implications of selfishly abandoning, of delivering, almost, this fabulous country to the most ruthless and destructive tyranny that has ever existed ... If Lhasa is finally conquered by the Reds, the loss will not be merely a local one. It will be a ghastly loss for the whole of Asia and also for every human being, the death of the most spiritual and inspiring country on this globe. [78] For some, Tibet had clearly moved to the centre of Western global mythologizing: What is happening in Tibet is symbolical for the fate of humanity. As on a gigantically raised stage we witness the struggle between two worlds, which may be interpreted ... either as the struggle between the past and the future, between backwardness and progress, belief and science, superstition and knowledge, -- or as the struggle between the wisdom of the heart and the knowledge of the brain, between the dignity of the human individual and the herd-instinct of the mass, between the faith in the higher destiny of man through inner development and the belief in material prosperity ... [79] Never before had Tibet functioned so clearly as a vessel for the projection of Western global fears and hopes. How did this unprecedented mythologizing come about? When Lowell Thomas wrote: 'Two World Wars have brought startling changes to most of the globe, but so far not to Tibet', he was reporting not historical circumstances but Western fantasies. Tibet had indeed changed dramatically between 1914 and 1949, but many in the West assiduously refused to acknowledge it. These Westerners lived in a split world. Quite clearly they knew about the turmoil of Tibetan history in the twentieth century, yet at the same time they disavowed it. The West seemed to need at least one place to have remained stable, untouched, an unchanging centre in a world being ripped apart. Many hoped that Tibet would be that 'still centre': [80] 'The Tibetans watched the whirlwind transformation of Asia, chaos and revolutions all around, the religious riots of India, the gradual disintegration of Nationalist China, the spreading anarchy of South-East Asia, and the Red tides from the north, with growing apprehension.' [81] Between 1904 and 1950, the political context within which the Tibetan drama unfolded had radically changed. Each of the three great empires upon which the destiny of Tibet had rested over the past 150 years had undergone upheaval. The old order had gone, the old rules of the game no longer applied. Two disastrous world wars had returned British attention to its own backyard. It slowly disengaged from its empire, and in 1947 India became independent. Britain was no longer much concerned about the political fate of Tibet. Russia too had suffered terribly in two world wars, had been torn apart by revolution and civil war. Tibet took advantage of this chaos to proclaim its independence and throw out the last vestiges of Chinese power -- its administration and its soldiers. For nearly forty years, between 1912 and 1951, Tibet enjoyed an uneasy autonomy. Western travelers into Tibet almost inevitably had to pass through this chaos, this terrible violence and lawlessness. Fleming and Maillart came from China across the northern boundary, Clark fought his way through eastern Tibet; Ossendowski escaped from Soviet Russia only to fall into the madness of Central Asian politics between the wars. In 1933 Fleming summarized it all: 'the situation ... was complex, lurid and obscure and seemed likely to remain so indefinitely'. [82] No wonder Tibet should seem a calm and exemplary home of sanity. In a world where modern ideology combined with modern weapons to bring havoc to the traditional cultures of the world, it was understandable that the excesses of Tibetan feudalism should pale into insignificance by comparison. In the nineteenth century, Britain had feared the encroachment of czarist imperialism into Tibet. During the years between the two global wars of the twentieth century their fears turned to Japanese militarism, to German and Italian fascism, and to Soviet expansionism. [83] After World War Two, with the empires of Russia and China more intact and coherent than ever before -- although now under the control of communism -- Tibet seemed an unlikely bastion against the spread of international Marxism. Nevertheless, the country's internal politics were by no means tranquil, but full of drama and incident. Chinese troops occupied large areas of eastern Tibet between 1907 and 1910, besieging and capturing monasteries, ruthlessly slaughtering monks. Lhasa was in the grip of anxiety and when, in February 1910, an advance guard of the Chinese army entered the capital, the Dalai Lama fled to India. In his absence the Chinese issued a decree, ignored by the Tibetans, that deposed him. But in 1911, following the overthrow of the Manchu Dynasty in Peking, the Chinese troops in Lhasa were forced out of Tibet. The Dalai Lama returned home in June 1912. [84] Despite the Simla Conference of 1913-14 between representatives of Tibet, China and Britain to establish the boundaries of Tibet, Chinese aggression continued in the eastern region. To the north, in Mongolia, the third great incarnated Lama, Djebtsung Damba Hutuktu Khan, the so-called 'Living Buddha' of Urga, was arrested in 1921 and deprived of his throne by the Soviets. He was temporarily reinstated by the victorious White Russian Army under Baron Unberg von Sternberg, but they were soon defeated and the 'Living Buddha' was once more deposed. He eventually died of syphilis in 1924. The Mongolian People's Republic was established; lamaism was ruthlessly crushed; monks were killed or defrocked; monasteries were destroyed. Mongolia had a closer spiritual relationship to Tibet than any other country. No wonder the 13th Dalai Lama wrote: ... the present is the time of the five kinds of degeneration in all countries. In the worst class is the manner of working among the Red people [USSR]. They do not allow search to be made for the new Incarnation of the Grand Lama of Urga. They have seized and taken away all the sacred objects from the monasteries. They have made monks to work as soldiers. [85] He warned that such things could well happen in the centre of Tibet. Yet at precisely the same time, Sir Frederick O'Connor, despite having lived in and around Tibet for many years as a British political officer, could write that nothing seemed to threaten the' aloofness', 'glamour' and calm of the country and its culture. [86] Rivalry between the Tashi (Panchen) Lama and the Dalai Lama resulted in the former fleeing for his life in 1923. He never returned to Tibet, and died in exile in 1937. The Dalai Lama had himself already died in 1933 and for over two years Tibet was without either of its great spiritual leaders -- a situation which led to confusion, uncertainty, and sometimes violence. [87] In 1932 war again broke out in eastern Tibet between Chinese warlords and Tibetan troops. In 1934 the famous 'Long March of Mao Tse-tung's communist army resulted in disruption and fighting on the eastern border. [88] As Bell wrote: 'By the beginning of 1936 it became clear that Tibet was in danger, not only from direct armed invasion by China, but also from a Chinese military penetration under the shadow of the Tashi Lama.' [89] In that year the British sent a political mission to Lhasa, under the leadership of Gould, to give the Tibetans political and military advice. Although the Soviets seemed to have given up any direct designs on Tibet after the failure of a mission to Lhasa in 1927-8, they consolidated their grip on Soviet Mongolia and all traces of Buddhism in that country vanished. Nevertheless, Red Army troops and Soviet technicians dominated the north of Sinkiang province -- causing considerable alarm among the British, who were concerned as always about the vulnerability of India's northern frontier and trade routes. [90] In 1940, whilst the rest of the world was caught up in war, the new, infant Dalai Lama was enthroned. In 1942 an American expedition led by Ilya Tolstoy passed through Lhasa in search of a new supply route from India to China, and was favorably received. Then, soon after the termination of the Second World War in 1945, Lhasa experienced a minor civil war. An assassination attempt was made on the current Regent by his predecessor, Reting Rimpoche, who was arrested and died mysteriously in gaol a few days later. His arrest was the catalyst for a small rebellion. The lamas at one of Sera monastery's four colleges murdered their Mongolian abbot and rose against the government. Troops were despatched and there was fierce fighting between the monks and the Tibetan army. After a few days the Sera monks finally surrendered. While this was a very localized disturbance, it nevertheless illustrates the unease and turbulence in the capital at that time. [91] In 1948 the Tibetan government sent four high officials on a world tour encompassing India, China, the Philippines, the USA and Europe. They were away for two years and it was hoped that the world had now become aware that Tibet was a stable, civilized and independent country. Nevertheless, it did not apply to join the United Nations. By early 1950, Heinrich Harrer could sadly muse: 'It was inevitable that Red China would invade Tibet'. [92] In October of that year the Chinese Red Army attacked the eastern frontier in six places simultaneously. (Ford, an English radio operator working for the Tibetan government in Chamdo was captured.) Tibet appealed to the United Nations for help, but it was rejected. Once again, in December 1950, the 14th Dalai Lama, a boy of fourteen, fled to the Chumbi valley. After a short stay he returned to Lhasa. The story of the next nine years was one of an increasing Chinese encroachment and infiltration, often met by armed Tibetan resistance. In 1959 the Dalai Lama again fled -- this time, it seems, for good. The Chinese, caught up in the fervor of the Cultural Revolution, destroyed most of the Tibetan monasteries, killed many of the monks, intimidated the rest and severely incapacitated Buddhism as a dynamic and living religious tradition in Tibet. Armed Tibetan resistance continued for several years. [94] Of course, until the 1950s most of this political turmoil was scarcely felt by the majority of the Tibetans, with the exception of those in the eastern regions or those in direct contact with the Mongolians and the inhabitants of Sinkiang province. Nevertheless, until the final invasion of the Chinese communists in 1959 many in the West still imagined Tibet to be unchanged and unchanging, a country frozen in time, impervious to the twentieth century, aloof, mysterious. Only when it was threatened by communism did the West seriously consider the final demise of this idealized Tibet. This, of course, was because communism was also feared in Europe and America. Communism was already mythologized, already the Antichrist, the bearer of the West's unadulterated shadow. Tibet was merely drawn into the mythic drama as the other side of the equation: the 'Most peaceful nation on earth' versus 'this soulless regime'. [95] 'Are the forces of evil', asked de Riencourt, 'going to blow out the faint light which shines on the Roof of the World, perhaps the only light which can guide mankind out of the dark ages of our modern world?' [96] To understand this extraordinary polarization into the extremes of good and evil, Tibet versus communism, we need to understand a previous polarization: that between Tibet and Western materialism. Shangri-La: the Geography of Hope and Despair Paralleling many Westerners' fears about the erosion of Tibet's supposedly unchanging 'Tradition' was an unprecedented disillusionment with their own culture. In his study of British writers who traveled abroad between the wars, Fussell shows that an aversion to Britain was common among them. He reminds us that Freud's Civilization and its Discontents was also a product of that era, and that the English translation of Spengler's Decline of the West appeared between 1926 and 1928. [97] The First World War administered a profound shock to Westerners' confidence in their own civilization. It was a time of doubt and reflection on a scale almost unknown in pre-war times. For example, Ronaldshay, Earl of Zetland, visited the Buddhist Himalayas between 1918 and 1921. Whilst deeply respectful towards Buddhism he was sceptical of the Tibetan variant, and in particular their obsession with the mantra 'Om Mani Padme Hum'. 'The determination to ensure the repetition to infinity of this amazing formula obsesses the minds of an entire people', he remarked. 'And yet', he mused, 'these hill folk are a happy people, always ready to laugh and joke ... a fact which should provide material of interest for the psychologist who would investigate the true source of happiness in the human race.' [98] Other travelers were not merely reflective, but totally dismissive of Western values and aspirations.

Alexandra David-Neel hated the thought of leaving her Himalayan retreat and returning to Europe: Sadly, almost with terror, I often looked at the thread-like path which I saw, lower down, winding in the valleys and disappearing between the mountains. The day would come when it would lead me back to the sorrowful world that existed beyond the distant hill ranges, and so thinking, an indescribable suffering lay hold of me'. [99] A few years later, in 1923, at the age of fifty-four, she set out for Lhasa disguised as a Tibetan beggarwoman on a pilgrimage: 'I delightedly forgot Western lands, that I belonged to them, and that they would probably take me again in the clutches of their sorrowful civilization.' [100] But this negative feeling about Western civilization was not simply a reaction to the Great War, even though the memory of that conflict lingered on. (Byron and Fleming, for example, both paid tribute to the war with brief, passing references.) [101] Certainly Byron considered the West spiritually empty. [102] As the twentieth century progressed, these negative feelings showed no sign of abating. After the end of World War II, for example, Harrer was gloomy about the situation in Europe: 'We did not miss the appliances of Western civilization. Europe with its life of turmoil seemed far-away. Often as we sat and listened to the radio bringing reports from our country we shook our heads at the depressing news. There seemed no inducement to go home.' [103] Migot, exploring in the southeast corner of Tibet in 1947, was scathing about Christian missionaries. 'It would really make more sense', he argued, 'if India or Tibet sent missionaries to Europe, to try and lift her out of the materialistic rut in which she is bogged down, and to re-awaken the capacity for religious feeling which she lost several centuries ago.' [104] Throughout this whole period many Western travelers were avidly searching for something in Tibet. At first this was confined to personal meaning, to a spiritual quest. Occasionally it was a search for ideas that could help the West find its way again. 'I would discover what ideas,' wrote Byron, 'if those of the West be inadequate, can with greater advantage be found to guide the world.' [105] By the close of the Second World War, the searching had become desperate. The disillusionment was all-embracing. Tibet seemed to offer hope, not just for a personal despair but for the malaise of an entire civilization, and perhaps for the whole world. James Hilton's Lost Horizon, first published in 1933, brilliantly encapsulated and popularized this symbolic drama. Hilton's novel was an outstanding best-seller in Britain and America, and was quickly made into a film. It introduced a new word and landscape into the English language -- Shangri-La'. The leading character, Conway, was one of the lost generation -- burnt out by the First World War, disillusioned by the post-war situation, alienated from his own extroverted, materialistic and spiritually shallow culture. But in a remote Tibetan-type monastery, hidden in the wilderness of the Kuen Lun Mountains that formed the northern boundary of Tibet, he found hope: 'The Dark Ages that are to come will cover the whole world in a single pall; there will be neither escape nor sanctuary save such as are too secret to be found or too humble to be noticed. And Shangri-La may hope to be both of these.' [106] It was imagined that Shangri-La would preserve the wisdom and beauty of civilization and be the faint light to guide the world. Hilton's 1933 vision of Shangri-La joined Blavatsky's mahatmas and Kipling's lama in Kim as one of the great mythologizings about Tibet. It was for this twentieth-century Tibet what the other two were for the fin-de-siecle Tibet. It gathered the threads of fantasy, shaped them, articulated them. When Thomas journeyed to Lhasa in 1949, he glibly wrote: 'Once we crossed the Himalayas into Tibet we were indeed travelers in the land of the Lost Horizon. And it often seemed as though we were dreaming -- acting the parts of characters in James Hilton's novel, on our way to Shangri-la.' [107] But more important than such direct but bland references to Shangri-La were the deeper disenchantments and aspirations that resonated in sympathy with Hilton's vision. '[My] dreams of Tibet helped to keep me going through the tragic days of collapse and the dark years of the Occupation.' So wrote the French explorer Migot about the fall of France in 1940. 'In Paris, joyless and crushed under the weight of defeat, the magic name had been for me the glimmer of light glimpsed at the end of a sombre tunnel ...'. [108] De Riencourt similarly began his account in the dark years of World War II. Incarcerated in a Spanish concentration camp he asked: 'Who ... could then doubt that Western civilization was doomed?' He then recounted talking to a fellow-prisoner, a Hindu: 'Suddenly he uttered a magic word which caught my attention -- Tibet.' De Riencourt stopped listening and instead floated off into a reverie: I pictured myself riding up to Tibet on a cloud, escaping altogether from this modern inferno of wars and concentration camps, searching for this forbidden land of mystery, the only place on earth where wisdom and happiness seemed to be a reality. [109] After the violence of the two world wars came the hostility of the Cold War, backed up by the terror of atomic weapons. Again the Tibetans offered hope: 'Isolated as they are in their mountain kingdom, undisturbed in their monasteries by war, unrest and the turmoil of modern civilization, they must have ample opportunity to reflect on the madness of the rest of the world.' [110] Did the Tibetans have any solutions for the global malaise? asked Thomas of the lamas in 1949. De Riencourt, too, mused: 'Was it possible that Tibet could provide an explanation of Asia's enigma, perhaps even an answer to modern man's problems?' [111] For many of these travelers it was questionable whether Western civilization had anything whatsoever of value to offer Tibet. The West seemed spiritually bankrupt, its ideas and inventions a hindrance -- perhaps even antithetical -- to human happiness. In 1931 Leslie Weir, the first Englishwoman in Lhasa, addressed the Royal Asiatic and Royal Central Asian Societies: 'We cannot realize how much we have sacrificed during these late years of scientific advance and of accelerated speed.' The Tibetans, she continued, 'have retained poise, dignity, and spiritual repose. All of these we have lost in our hectic striving towards scientific achievement. Can civilizations based on science alone, advance healthily if divorced from the spiritual side of life?' [112] A few years later, Byron posed a similar question, albeit in a more sophisticated manner: To a country, moreover, where justice is cruel and secret, disease rife, and independent thought impossible, Western ideas might bring some benefits. But could the benefits outweigh the disadvantages? In the present state of Western civilization, whose spiritual emptiness in relation to Asia is masked by a brutal assumption of moral superiority, it seems to me that they could not. I prefer to hope that the life we saw at Gyantse will endure, and to wish Tibet luck in her isolation, until such time as the West itself is reformed and can commend its ideas with greater reason to those who have hitherto escaped them. [113] In 1940 Guibaut's ponderings covered similar terrain. 'Will that which is to come be an improvement?' he asked. [114] At no other time had the West created Tibet in such direct opposition to its own culture. While Tibet had always been imagined as the Other, this Otherness had never before been pictured as a simple opposite, whether for better or worse, of Western values. Oppositional thinking is itself highly symbolic and when treated literally, in terms of exclusive categories, blocks paradox and the deepening of the imagination. It has been suggested that such antithetical thinking is a neurotic habit, highlighting a feeling of powerlessness or, conversely, a desire for control. [115]

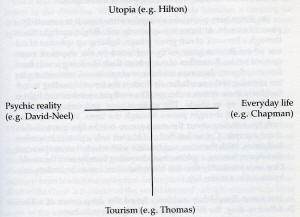

In 1929 David-Neel wrote about her journey into Sikkim, where she encountered the summer resorts established in the mountains by the British: 'A few miles away from the hotels where the Western world enjoys dancing and jazz bands, the primeval forest reigns.' [116]Twenty years later, de Riencourt set up the same kind of opposition. At Gyantse he was welcomed into the British trade agency, listened to 'a dance music', drank cocktails: But I had only to step out ... and, under the moonlight ... the sprawling lamasery with its hundreds of lighted windows, the distant and mysterious sound of trumpets and drums, the intense cold which made me shiver, everything brought me back to reality. [117] For these travelers primal consciousness alone was real, the rest was decadence and frippery. In 1933 Byron directly counterposed: Russia and Tibet: Russia, where the moral influence of the Industrial Revolution has found its grim apotheosis; Tibet, the only country on earth where that influence is yet unknown, where even the cart is forbidden to traverse plains flatter than Daytona Beach, and the Dalai Lama himself rides in a man-borne palanquin ... In Russia the tradition has succumbed to the machine. In Tibet it has remained as completely immune from it ... Russia is lower and more colorless, Tibet higher and more colored, than any country on earth. [118] In 1949 Harrer was still posing the same dichotomy: 'It is a question whether the Tibetan culture and way of life do not more than balance the advantages of modern techniques. Where in the West is there anything to equal the perfect courtesy of these people?' [119] Tucci wrote that among Tibetan recluses one 'finds in contemplation poise which we are seeking in vain'. [120] Contradictions became simplified, paradoxes easily resolved, under the sway of oppositional thinking. The gross subservience encouraged by Tibetan feudalism was forgotten as perfect courtesy was singled out and reified. The West came to be represented either by bad manners, junk and destructive technology, or by dance music and cocktails. De Riencourt groaned: 'The telephone! Was there no place on earth where one could be protected from the curse?' [121] He conveniently forgot that the Dalai Lama himself had insisted on introducing the telephone to Lhasa, and that such modern communication was deemed essential for Tibetan self-defence. 'How will these Tibetans react when technical civilization reaches them, as it eventually must? Will they then ever regain that happiness and peace of mind which they will, just as surely, lose?' [122] Sociological, political, historical and psychological complexities simply vanished beneath the deceptively facile opposition of technology versus peace of mind. Oppositional thinking cannot be simply adopted as an explanation of the imaginative creation and structure of this twentieth-century Tibet, which was not just born out of a disillusionment with Western culture after 1918 [123], but was also supported by the century-old tradition of Western imagining about that country. We need to go deeper into the dynamics of this Western fantasy-making. Outside Time and Space For Western travelers, Tibet was still a land outside time and space, a 'Lost World', a place 'Out of this World'. Giuseppe Tucci wrote: 'To enter Tibet was not only to find oneself in another world. After crossing the gap in space, one had the impression of having trailed many centuries backward in time.' [124] Guibaut, too, insisted: 'Whilst other countries are being drawn closer together, while time and space are losing the permanent value which they have possessed for thousands of years ... Tibet, far removed in time and knowledge from our now crazy civilizations, has not changed.' [125] Tibet was still seen as a land of 'limitless horizons', deceptive distances, immense empty spaces. [126] To go there was to leave the twentieth century behind, to enter a pre-scientific world. [127] Confronted by such a place, de Riencourt mused: 'Here is a living past, so alive and powerful in fact, that one doubts if time is anything more than a convenient symbol invented by modern man ...'. [128] Life in Tibet seemed indifferent to time. In the Tsaidam marshes at its northern edge, Fleming humorously recounted meeting 'an itinerant lama from Tibet; he lived in a small blue tent with an alarm clock which was either five hours fast or seven hours slow'. [129] Chapman, accompanying a British diplomatic mission to Lhasa in 1936-7, had close dealings with the Tibetans and constantly referred to their crazy timekeeping. [130] There always seemed to be plenty of time in Tibet -- an enviable situation for most Westerners. [131] But this image of Tibet no longer dovetailed with British or Western imperial mythologizing. True, it still coincided with British strategic thinking about India's northern frontier, but unlike the situation at the turn of the century, this all now seemed marginal to the fantasy-making of travelers. The Tibetans might still be just as 'majestically vague' about geography, just as indifferent to exact timetables, as they had been fifty years earlier, but such things no longer infuriated Western travelers. [132] Although it was occasionally frustrating, this vagueness was now always tolerated, excused and, more often than not, made into a virtue. Not only had imperial mythologizing changed, so too had the struggle over the definition of time and space. Such a struggle was no longer at the leading edge of cultural change in the West. Tibet's status as a no-man's-land had depended upon the stability of its surrounding geographical and historical conditions. This stability no longer existed -- indeed, Tibet was itself considered to be under threat, not just probably but inevitably. If it was to preserve its imaginative place outside time and space, it clearly had to be located somewhere other than in reference to literal physical geography and politics. Utopias, tourist landscapes, everyday life and psychic realms, in addition to sacred places, all seem to have a timeless disregard for history and politics -- at least, that is how they have been consistently imagined and constructed in the West. Tourism, for example, can often create pseudo-places: monuments and experiences frozen in time. Already, in the period between the wars, travelers' contempt for mass tourism was being superseded by a kind of tourist Angst, a feeling of being trapped within an unreal facade. [133] The turmoils and terrors of history, with its wars and revolutions, were also precipitating a retreat into the closed, safe, timeless and localized world of everyday life, with its manageable and comfortable routines. [134] The popularity of psychoanalysis, psychic research, surrealism and occultism after 1918 also tended to celebrate a timeless, dematerialized world. [135] As we shall see, each of these imaginative domains provided the fantasies of Tibet, seemingly so similar to those of the nineteenth century, with radically new contexts, but before examining these we need to focus attention on yet another new imaginative context for Tibet: that of a utopia. Utopias and Sacred Places In 1936 Marco Pallis was camped on Simvu Mountain in the eastern Himalayas, gazing up at the awesome peak of Siniolchu: But there was something else which ... drew our gaze even more than that icy spire. To the left of it, through a distant gap in the mountains, we could just make out lines of rolling purple hills, that seemed to belong to another world, a world of austere calm ... It was a corner of Tibet. My eyes rested on it with an intensity of longing. [136] In the phenomenology of the imagination, utopias and sacred places are different. Sacred places are entrances to paradox: they embody tension and contradiction; utopias resolve these, eliminate them. At the centre of the sacred place is the axis mundi, the axis that connects heaven, earth and the Underworld. In a sacred place light and dark meet; it is a place of fear as well as one of awe and worship. But with a utopia, the darkness is always outside, excluded. Paradox is not suffered, but removed. Sacred places help to orientate the world; they are part of the social fabric. Regular journeys can, and must, be made to and from such places so that bearings can be taken, guidance received and communication occur with the gods. Utopias by contrast are separated from social life by a revolutionary abyss. They are places of hope and aspiration. Whilst sacred places are for temporary visits, utopias are for future dwelling. Sacred places usually help to stabilize the world, and provide sites for worship and prayer. Utopias, on the other hand, while often escapist, may also provide imaginary places where an alternative society can be envisaged; places where visions can be brought to life and experiments tried out; vantage points where criticism can be directed back at established society. [137] As the twentieth century moved towards its midpoint, Tibet virtually ceased to be a true sacred place and instead was transformed into a Utopia. Of course, this was not achieved without a struggle. In the accounts of travelers such as David-Neel, Byron, Maraini, Chapman and Harrer, attempts were made to sustain paradox and contradiction. Nor was utopianizing the only option. The place of Tibet was also becoming psychologized, normalized, and also prepared for tourist fantasies. Hilton's novel Lost Horizon, first published in 1933, was the quintessence of a Tibetan utopia. It had an essential authenticity about it --not in the sense of being empirically feasible, but of conforming to the reality of contemporary fantasies about Tibet. The established images are clearly recognizable: the air in Shangri-La is as' clean as from another planet'; the 'thin air had a dream-like texture, matching the porcelain-blue of the sky'; it is a totally separate culture 'without contamination from the outside world', especially from 'dance-bands, cinemas, sky-signs'; there is no telegraph; there is a mystery, which, it is suggested, 'lies at the core of all loveliness'; time means less -- indeed, there is time to spare; Shangri-La is built around the principles of moderation and good manners; the mountains surround it like 'a hedge of inaccessible purity'. [138] The valley itself is a fertile paradise in the midst of a wilderness. Even gold in abundance is to be found there. [139] Also the leading protagonist, Conway, bore a close resemblance to the idolized English Everest climber Mallory. Like Conway, Mallory was strikingly good-looking, surrounded by a kind of mythical aura. Indeed, he was frequently referred to as Sir Galahad. Like Conway, Mallory was a man of decisive action, yet also vague and unworldly. Both men had sufficient mystical inclination to satisfy the spiritual longings of the British public, but not so much as to arouse their suspicions. When Mallory died in 1924 making his attempt on the summit of Everest, his death became a symbol of human inspiration, of the struggle of the spirit against matter, of idealism over the mundane. [140]