|

OBAMA, THE POSTMODERN COUP -- MAKING OF A MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE |

||

|

FORESHADOWINGS OF OBAMA FROM A QUARTER CENTURY AGO Project Democracy's Program: the Fascist Corporate State (The following are excerpts from an article by Webster G. Tarpley which appeared in Project Democracy: The Parallel Government Behind the Iran-Contra Affair, published by EIR in April 1987.) Even in an epoch full of big lies like the late 20th century, it is ironic that the financiers of the Trilateral Commission should have chosen the name "Project Democracy" to denote their organized efforts to install a fascist, totalitarian regime in the United States and a fascist New Order around the world. It is ironic that so many of the operatives engaged in the name of "democracy" in this insidious, creeping coup d'etat against the United States Constitution should be first and second-generation followers of the Soviet Russian universal fascist, Nikolai Bukharin. Though ironic, all these propositions are indeed true. Project Democracy is fascist, designed to culminate in the imposition of fascist institutions on the United States, institutions that combine the distilled essence of the Nazi Behemoth and the Bolshevik Leviathan. Project Democracy is high treason, a conspiracy for the overthrow of the Constitution. An organization whose stock in trade is the destabilization and the putsch in so many countries around the world can hardly be expected to halt its operations as it returns to the U.S. border. For Project Democracy, it can happen here, it will happen here. The greatest obstacle to understanding the monstrous purpose that lurks behind Project Democracy's bland and edifying label is the continued ignorance on the part of the American public of the real nature of 20th-century totalitarian regimes. Despite the fact that Stalin deliberately helped bring Hitler and the Nazis to power, despite the Nazi-Communist alliance of 1939-41 under the Hitler Stalin Pact, despite Mussolini's close ties to Moscow, despite the deep affinity between Nazi-fascists and communists demonstrated repeatedly in many countries by mass exchanges of membership between political organizations of the two persuasions, the average American still sees communism and Nazism-fascism as polar opposites. The expression "fascist" exists only as a strongly derogatory but very vague epithet, empty of any precise political content. "Totalitarianism" is much more than just a dictatorship or authoritarian state. The totalitarian state seeks to dictate the behavior of its inmates down to the most minute detail, and creates for this purpose institutions that will allow that total surveillance and total control. In Byzantine-Orthodox civilization and in the Western totalitarianism copied from it, all departments of human endeavor, including economics, religion, sports, marriage, and even thinking are conceived of as departments of the state. Appropriate institutions are required to mediate totalitarian control in each of these areas. In totalitarianism both the individual and society disappear into the maw of the all-consuming Moloch, the state. A DEFINITION OF FASCISM Starting from these premises, it is possible to furnish a rough definition of modern fascism or Nazi-communism, the regime toward which Project Democracy is working. That definition contains the following elements: 1. Totalitarian fascism starts as a radical mass movement sponsored by bankers which, if it is able to seize power, produces a regime or governing system which seeks to mutilate, mortify, and crush the conception of the individual. As in the writings of Mussolini's ideologue, Giovanni Gentile, or in the ravings of Michael Ledeen, the aspirations of the individual are rigidly subordinated to the exigencies of the regime.

2. The fascist regime is a government controlled in practice by a single party -- a one-party state. 3. Fascist ideology, whatever its specific predicates, repudiates human reason and exalts irrationalism and irrationalist violence, often in the form of wanton military aggression and imperialism. A fascist mass movement is the most aggressive form of militant irrationalism. From Mussolini's romanita through Hitler's Herrenvolk, fascist ideology is based on notions of racial superiority and race hatred, extreme chauvinism, and blood and soil mysticism. Fascism is neo pagan and ferociously hostile to Augustinian Christianity, as can be shown from Mussolini's early career and from Hitler's private conversations. 4. Fascist economics is the murderous austerity associated with the names of Hitler's finance minister, Hjalmar Schacht, and Mussolini's finance minister, Count Giovanni Volpi di Misurata. The final logic of fascist economics is the concentration camp, the labor camp, the Gulag. Fascist irrationalism cannot tolerate scientific rationality on a broad scale, and is therefore correlated with hostility to technological innovation, and permanent peasant backwardness in agriculture. 5. The institutions through which totalitarian control of economic life is mediated merit special attention. In totalitarian regimes in the Western world, masses of labor have often been simply dragooned through institutions such as Dr. Ley's Nazi Labor Front. But the characteristic institutions of fascism in the West are those of the so-called corporate state. In the fascist regime of Italy, Vichy France, and many others, it was the corporations which were to bring together ownership and employees, management and labor under the direct control of the one-party state, for the purpose of extending totalitarian domination into the nooks and crannies of everyday economic life, while at the same time fragmenting potentially rebellious workers along the lines of branches of industry. THE CORPORATIST PRINCIPLE This corporatist principle in fascism is so neglected and misunderstood that it merits our special attention, especially because the form of fascist totalitarianism which Project Democracy aims at is of a corporatist variety. The word corporation here has nothing to do with its usual English meaning of a joint-stock company. "Corporation" here means, approximately, a guild. For present purposes it is enough to recall that corporatism emerged as an irrational, solidarist opposition to capitalism and the United States Constitution during the period of the reactionary Holy Alliance after the end of the Napoleonic wars. Corporatism asserted that the way to overcome the tensions between labor and capital was not through the broad national community of interest prescribed by Alexander Hamilton's American System of dirigist political economy, but rather through the artificial creation of medieval guild organizations, based on the pretense that capitalists were masters, and workers were journeymen and apprentices, all functioning together in "organic" unity. Thus, Mussolini advertised his fascist regime as the stato corporativo or corporate state, proclaiming that "O ilfascismo sara corporativo o non sara" (fascism is corporative or it is nothing). In German, the equivalent for statocorporativo is Standestaat, wherein Stand has the meaning of estate or social group in the sense of aristocracy, clergy, and bourgeoisie, which along with the peasantry were the four "estates" of pre-revolutionary France. Hitler's National Socialist German Workers Party was corporatist from the very beginning: point 25 of the "unalterable" program of the Nazis as adopted on Feb. 25, 1910 included the "creation of corporative and professional chambers" (Die Bildung von Stande und Berufskammem zur Durchfuhrung der vom Reiche erlassenen Rahmengesetze in den einzelnen Bundesstaaten.) [Note 1] For a certain period after Hitler's seizure of power in 1933, his regime referred to itself prominently as a Standestaat, or corporate state. When Marshal Petain and Pierre Laval created their Nazi puppet-state in Vichy, Petain announced that one of the principal goals of his "national regeneration movement" was the creation of an ordre corporatif. Other fascist regimes, especially the many that were directly modeled on the Italian one, also stressed corporatism, so that corporatism emerges as the characteristic institutional structure of fascism. Theories of the corporate state can be traced back to Germans like Pesch and Kettler, or to the "guild socialism" of the Englishman William Morris. An early attempt to actually create a corporate state came in 1919, with the filibustering expedition to Fiume of Gabriele D'Annunzio, the proto fascist of our epoch. D'ANNUNZIO AS SEEN BY LEDEEN The corporate state D'Annunzio attempted to create during his Fiume adventure is of double relevance to an analysis of the fascism of Project Democracy. On the one hand, D'Annunzio's 16-month tenure as dictator in Fiume was the model and dress rehearsal for Mussolini's March on Rome. On the other hand, D'Annunzio's activities in Fiume have been the subject of a lengthy treatise by the most overt and blatantly fascist ideologue of Project Democracy, Michael Ledeen. Ledeen's discussion of D'Annunzio in Fiume is to be found in his book, The First Duce. Ledeen celebrates the poetaster D'Annunzio as the founder not only of fascism, but of 20th-century politics in general, through his creation of a Nazi-communist mass movement of irrationalism: Virtually the entire ritual of Fascism came from the "Free State of Fiume": the balcony address, the Roman salute, the cries of "aia, aia, alala," the dramatic dialogues with the crowd, the use of religious symbols in a new secular setting, the eulogies of the "martyrs" of the cause and the employment of their "relics" in political ceremonies. Moreover, quite aside from the poet's contribution to the form and style of fascist politics, Mussolini's movement first started to attract great strength when the future dictator supported D'Annunzio's occupation of Fiume. (p. viii) D'Annunzio's political style -- the politics of mass manipulation, the politics of myth and symbol, have become the norm in the modern world. All too often politicians and parties have lost sight of the point of departure of our political behavior, believing that by now ours is the normal political universe and that the manipulation of the masses is essential in the political process. D' Annunzian Fiume seems to have marked a sort of watershed in this process, and that is perhaps the explanation for the fascinating symbiosis between themes of the "Right" and the "Left" in the rhetoric of the comandante. It is of the utmost importance for us to remind ourselves that D'Annunzio's political appeal ranged from extreme Left to extreme Right, from leaders of the Russian Revolution to arch-reactionaries. (p. 202) Michael Ledeen is especially fascinated by D'Annunzio's ability to recreate an "organic" unity out of the disparate elements of modern society: "At the core of D'Annunzian politics was the insight that many conflicting interests could be overcome and transcended in a new kind of movement." (p. ix) For Ledeen, the key institutional feature of the D'Annunzian fascist order is the corporate state. The city of Fiume lies at the southern base of the Istrian peninsula, at the north end of the Adriatic Sea, across from Venice. In 1919 it was a former territory of the newly defunct Austro-Hungarian Empire under dispute between Italy and the new nation of Yugoslavia, where the town is located today under the name of Rieka. Italy, having participated in the victorious cause of the Allies, desired to annex Fiume as it had the other Austro-Hungarian port of Trieste, but the weak Nitti ministry hesitated to do so because of the opposition of France. France at that time was determined to emerge as the protector of the new states created in the Balkans by the Peace of Paris, and therefore supported the Yugoslav claim to Fiume, which the Yugoslavs saw as a key port. In order to force the hand of Nitti, D'Annunzio, starting from Venice, gathered a force of arditi, veterans of the elite shock troops of the Italian army, and seized Fiume in September 1919, demanding that Italy annex it. D'Annuzio's regime, which he sometimes called a Regency, organized acts of terrorism and piracy. In November 1920, with the Treaty of Rapallo, Fiume was made a free city. D'Annunzio refused to accept this solution and Italian troops dispersed his "legions" some time later. The Fiume expedition was a classic example of Venetian cultural-political warfare, designed as a pilot project for fascist movements and coups in the aftermath of the hecatomb of the First World War. The centerpiece of the operation was the so-called Charter of Camaro (Carta del Carnaro), the corporatist guild constitution for Fiume as an independent city, written by D'Annunzio in collaboration with the anarcho-syndicalist agitator Alceste de Ambris. The Carta del Carnaro was reminiscent of certain features of the Venetian Republic. Legislative power was vested in a bicameral legislature. One house was called the Consiglio degli Ottimi, or Council of the Best, and was elected on the basis of universal direct suffrage with one councilor per every thousand inhabitants. The Ottimi were to handle legislation regarding civil and criminal justice, police, the armed forces, education, intellectual life, and were also to govern the relations between the central government and subdivisions or states, called communes. The corporate chamber of the Fiume parliament was to be the Consiglio dei Provvisori, a kind of economic council. The Consiglio dei Provvisori was composed of representatives of nine guilds or corporations whose creation was also provided for in the document. These included the industrial and agricultural workers, the seafarers, and the employers, with 10 representatives each; the industrial and agricultural technicians, private bureaucrats and administrators, teachers and students, lawyers and doctors, civil servants, and cooperative workers, with five representatives from each group, for a grand total of 60. The Consiglio dei Provvisori was responsible for all laws regarding business and commerce. It also decided all matters touching labor, public services, transportation and the merchant marine, tariffs and trade, public works, and medical and legal practice. The Ottimi served for a term of three years, and the Provvisori for two years. A third legislative body was prescribed, formed through the joint session of the Ottimi and Provvisori: This was called the Arengo del Carnaro, and was to deal with treaties with foreign states, the budget, university affairs, and amendments to the constitution. The Provvisori were chosen by nine corporations. Membership in one of these corporations was obligatory for all citizens, and was posited in the Carta del Carnaro as an indispensable precondition for citizenship. The article on corporations states that "only the assiduous producers of the common wealth and the assiduous producers of the common strength are complete citizens of the Regency, and with it constitute a single working substance, a single ascendant fullness." (Ledeen, p. 166) D'Annunzio's corporations are horizontal, similar to the estates, and are not organized according to vertical branches or cycles of economic activity, as Mussolini's corporations were to be. The Carla del Carnaro provides for a 10th corporation, which seems to have been reserved for geniuses, prophets, and assorted supermen. D'Annunzio's conception of the corporation is almost tribal, as the text of the constitution shows. He stipulated that each corporation was to "invent its insignia, its emblems, its music, its chants, its prayers; institute its ceremonies and rites; participate, as magnificently as it can, in the common joys, the anniversary festivals, and the maritime and terrestrial games; venerate its dead, honor its leaders, and celebrate its heroes." (Ledeen, p. 168) The executive power was normally vested in seven rectors or ministers (including foreign affairs, treasury, education, police and justice, defense, public economy, and labor). For periods of emergency, it was provided that the Arengo could appoint a dictator or comandante for a specified term, as was the custom in the Roman Republic. There was also a judiciary, with communal courts (Buoni uomini, or good men), a labor court (giudici del lavoro), civil courts (giudici togati, or judges in toga) a criminal court (giudici del maleficio), and a supreme court called the Corte della Ragione, or court of reason. For Ledeen, D'Annunzio assumes the status of Nazi-communist prophet of the mass irrationalism of the 20th century. For Ledeen, the Carta del Carnaro sums up the "essence of European radical socialism." From the point of view of Ledeen's universal fascism, D'Annunzio is located in the same tradition as the classics of Marxism and historical materialism, since his writings conjure up the Karl Marx of the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844. The young Marx, like many other heirs of Hegelianism, had been engaged in the search for a way to end human "alienation," and D'Annunzio saw the structure created by the Carta as a means of organizing a society in which human creativity would blossom in a way rarely seen in the story of mankind. It is by no means accidental that he employed the language of the Communes [Italian city-states of the 1200s] in his new constitution, for he wished to recreate in the regency of Fiume the ferment of activity that had produced the Renaissance. He hoped that this constitution would produce a new, unalienated man." (Ledeen, pp. 168-9) In reality, D'Annunzio was a degenerate monster, a coprophile, pervert, and psychopath -- qualities that may have helped to determine Ledeen's compulsive affinity for this hideous figure. The Venetian operative D'Annunzio, the "John the Baptist" of fascism in this century, must bear a great share of the responsibility for opening the door to the Nazi-communist chamber of horrors in the epoch during and after the First World War. Ledeen's commitment to the creation of a universal fascist yoke has found its appropriate organizational expression in Project Democracy. MUSSOLINI'S CORPORATE STATE After the March on Rome in 1912, and especially after the consolidation of a full-blown dictatorship through the coup d'etat of 1925, the Kingdom of Italy saw the creation of the fascist corporate state. The promise of creating corporations figured prominently in Mussolini's demagogy from the beginning of his campaign for the seizure of power, but the creation of the corporations and the transformation of the parliament in order to include them was a long and drawn-out process that was completed only in the late thirties, at the eve of the outbreak of the Second World War. One of the reasons it took so long to found the corporations was the lack of agreement about what these artificial creations might in fact be, since they had to be invented ex novo. Mussolini in the end settled on the idea that each corporation was to represent, not a stratum of society, but rather a branch of industry. The essence of the fascist corporations was that they were a support and appendage of the personal rule of Il Duce, and thus of the one-party fascist state. As one historian has observed: "The fundamental truth, however, is that the Fascist State claims the right to regulate economic as well as other aspects of life, and has aimed at accomplishing the former through the Corporate organization. The Dictatorship is the necessary rack and screw of the Corporate system; all the rest is subordinate machinery." [Note 2] Mussolini rejected both the Marxist idea of class conflict as well as what he called economic liberalism. The corporate system was designed, in his view, to overcome the class struggle of the one and the exaggerated economic individualism of the other. All of this was supposed to mobilize and focus national energies in the service of the superior interest of the state as the overarching collectivity. In one speech, II Duce summed up the three elements of revolutionary corporatism as a single party, a totalitarian state, and "the highest ideal tension." In fact, Mussolini danced to the tune of Venetian financiers like Volpi di Misurata, Cini, and others. Mussolini situated the need for corporations in the context of the dissolution of the world capitalist system -- an interesting parallel to the corporatist fascism of Project Democracy and the Trilateral Commission, which are explicitly proposed as necessities for a post-industrial era of scarce and diminishing resources. In 1933, Mussolini announced that the world depression (or the "American crisis," as he also called it) had become a total crisis of the world capitalist system. He went on to distinguish three periods in the history of capitalism: "the dynamic, the static, and the declining." According to Mussolini, the dynamic era of capitalism extended from the introduction of the widespread use of the steam engine to the opening of the Suez Canal in 1870; this period he saw as the time of unfettered free enterprise. After 1870, came a static phase, with the growth of trusts, the end of free competition, and smaller profit margins. The third or decadent phase is described by Mussolini as a kind of state capitalism. Mussolini described the system in these terms: "The outcome is the necessity for corporatism: Today we are burying economic liberalism, and the Corporation plays that part in the economic field, which the Grand Council and the Militia [the squadristi] do in the political. Corporatism means a disciplined, and therefore a controlled economy, since there can be no discipline which is not controlled. Corporatism overcomes Socialism as well as it does liberalism: it creates a new synthesis." (Finer, pp. 501-502) The juridical basis for the fascist corporations is established in the Charter of Labor of 1927, whose sixth article states: "The corporations constitute the unitary organization of production and represent completely its interests. In view of this complete representation, the interests of production being national interests, the corporations are recognized by law as organs of the State." [Note 3] The regime created fascist labor unions for workers, which had the monopoly of representation of labor in the negotiation of the national labor contract for each category or branch of economic activity. The Confindustria was created as the sole syndicate of the employers. No labor contract was considered valid until it had been approved by the Ministry for Corporations. In 1934, Mussolini finally issued a decree-law creating 22 corporations for the principal sectors of the Italian economy. Each corporation was given a council, which was composed of equal numbers of representatives of the fascist labor union and the fascist employers' organization for that sector, plus representatives of the National Fascist Party, the Ministry of Corporations, and consulting technocrats. The president of each corporation was generally a top official of the government or of the Fascist Party. The leading task of each corporation was the reconciliation of disputes between labor and management. Each corporation represented a "productive cycle" rather than an occupational category. A first group of corporations included agricultural, industrial, and commercial elements. These were the corporations for: cereals; garden products, flowers, and fruits; vineyards and wine; oils; beets and sugar; animal industries and fishing; wood; and textile products. A second group of eight corporations included only commercial and industrial elements. These were: metallurgy and mechanics; chemical industries; clothing and accessories; paper and the press; building construction; water, gas, and electricity; extractive industries; and glass and ceramics. A third group of corporations made up the service sector: insurance and credit; professions and arts; sea and air transportation; internal communications; show business; and tourism and hotels. In the early stages of the regime, corporate representatives were brought together at the national level in a National Council of Corporations, and a National Assembly of Corporations, which were later superseded by a Central Corporate Committee. All of these contained party and government representatives in addition to the corporate delegates. Councils of Corporate Economy were also set up in each province as a kind of fascist chamber of commerce, with all the corporations of the province plus local governments being represented. In 1938, after having proclaimed that he considered the Chamber of Deputies, which until that time had been the lower house of the Italian Parliament, as belonging to the alien residue of liberalism, Mussolini replaced that Chamber with the Chamber of the Fasces and Corporations (Camera dei Fasci e delle Corporazioni). This was composed of a number of delegates appointed by each of the corporations, plus other delegates appointed by the National Fascist Party. Mussolini summed up these institutional transformations with the following words: "We have constituted a Corporative and Fascist State, the State of national society, a State which concentrates, controls, harmonizes, and tempers the interests of all social classes, which are thereby protected in equal measure. Whereas, during the years of demo-liberal regime, labor looked with diffidence upon the State, and was, in fact, outside the State and against the State, and considered the State an enemy of every day and every hour, there is not one working Italian today who does not seek a place in his Corporation or syndical federation, who does not wish to be a living atom of that great, immense living organization which is the national Corporate State of Fascism." (Field, p. 16) After the cataclysm of the Mussolini regime, former members of the fascist hierarchy who considered themselves in the syndicalist-corporate tradition, such as Giuseppe Bottai, accused Mussolini of having been instinctively inclined to preserve his personal dictatorship, rather than transform that dictatorship into a true corporatist system. From beginning to end, the corporations were in fact the merest paraphernalia of Il Duce's one-party state. Although he actually functioned as a malleable puppet of Volpi di Misurata and the Venetian financiers, in the eyes of the world Mussolini stood atop the fascist edifice as Duce of Fascism and Head of Government, and the secretary of the National Fascist Party served at his pleasure. An important organ of this totalitarian dictatorship was the Grand Council of Fascism (Gran Consiglio del Fascismo), primarily an expression of the fascist party, but in its makeup a mixed organ composed of top officials of the National Fascist Party, government ministers, the Presidents of the Senate and the Chamber, the commander of the squadristi, and others. As long as the Chamber of Deputies lasted, it was the Grand Council which made up the single nationwide list of Fascist candidates which the voters were called upon to accept or reject as a single unitary slate. The Grand Council was also responsible for submitting to the King the names of persons who might be selected as Head of Government. It was this Grand Council which, in July 1943, decided to oust Mussolini. As will be shown later, the National Endowment for Democracy is not only corporatist, but its board of directors is intended to function as a kind of informal Grand Council of Fascism in the totalitarian one-party state that Project Democracy seeks to create in the United States. After seizing power, Mussolini institutionalized and domesticated his storm troopers, the squadristi, under the name of the Voluntary National Security Militia, which was an organ of the Fascist Party. To combat political resistance to his regime, Mussolini then set up Special Tribunals whose judges were all high officers of the squadristi militia. Perhaps Ledeen or other Project Democracy theorists can take this as a starting point for the reform of the U.S. federal judiciary. Mussolini claimed to justify his regime through the need for efficiency and getting things done effectively. The Second World War revealed the overwhelming logistical and military weakness of the fascist corporate state. Despite the failure of corporatism in its declared aims of generating economic and military power, corporatist forms have exercised an almost hypnotic fascination over certain financier cliques in times of grave economic crisis. As we will see, the Trilateral Commission is committed to a neo-corporate order for the United States. At this point in the argument, certain readers may become impatient with an argument that seems to them to be incongruous. Can it be that the business-suited bankers of the Trilateral Commission, the shirt-sleeve bureaucrats of the AFL-CIO, or even such figures as Oliver North share decisive elements of their ideology with a black-shirted, jack-booted, strutting fascist like Mussolini, with fez, dagger, and club, with jaw jutting over the balcony of the Palazzo Venezia? Are not the present-day figures of Project Democracy too bland to qualify as fascists? Are they not just American pragmatists with views that may happen to differ from our own? It may come as a surprise to many that Mussolini himself was a professed follower of American pragmatism. Among the thinkers who had made the greatest contribution to his own intellectual formation, Il Duce numbered first of all William James, the classic exponent of American pragmatism, whom he knew especially through the Italian writer Papini. Then came Machiavelli (for window-dressing, since he was certainly not a pragmatist and clearly not understood by Il Duce), followed by Nietzsche, an authentic proto-fascist who can be considered as representing a slightly different school of pragmatism. Then came the French anarcho-syndicalist, Georges Sorel, the theorist of purgative violence and also a declared pragmatist.

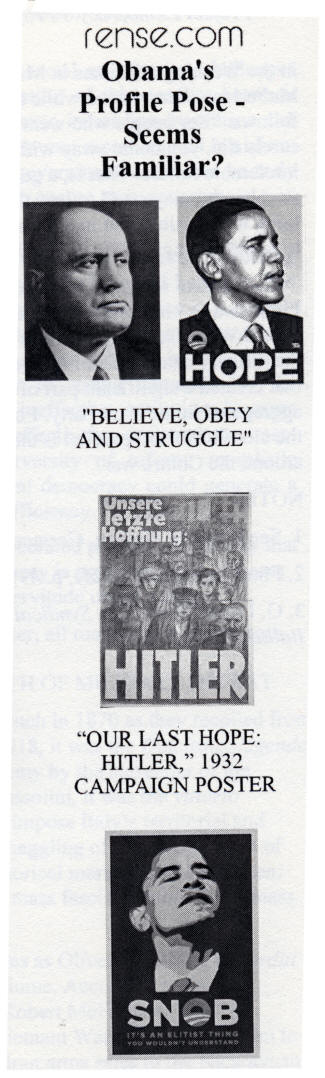

All pragmatists are not necessarily fascists, but in the 20th century many have been, and there is no doubt that all fascists are pragmatists. In a crisis of civilization like the one of the 1980s, the fascists constitute the fastest-growing component of the pragmatic school. This makes it possible for individuals like Oliver North and Carl Gershman to embrace fascism as a simple practical expedient. In one of his speeches, Mussolini remarked: "The second foundation stone of Fascismo is represented by anti-demagogism and pragmatism." William Yandell Elliott of Harvard University remarks in his study of post-World War I political irrationalism, entitled The Pragmatic Revolt in Politics: "For pragmatism, a myth is true so long as it works. Mussolini offers himself as the new Caesar if he can capture the imagination of Italians and inflame them with his dream, he feels that he can govern with consent." (p. 341) Elliott, it should be recalled, was one of the principal teachers of Henry Kissinger. William James had posited this "working test of truth," which was also reflected in Mussolini's celebrated contempt for programs. When asked for a program, he replied: "Our program is simple: We wish to govern Italy. They ask us for programs, but there are already too many of them." For Mussolini, program was a part of liberalism's "government by talk," which he was determined to extirpate. In 1932, Mussolini wrote: "La mia dottrina era stata la dottrina dell'azione. Il fascismo nacque da un bisogno d'azione efu azione." (My doctrine had been the doctrine of action. Fascism was born of the need for action, and was action.) Oliver North would presumably agree. THE TRILATERALS' U.S. CORPORATE STATE From the moment of its inception about a dozen years ago, the operational network known today as Project Democracy has had as its goal the subversion of the United States constitutional order in favor of a one-party, totalitarian and corporatist fascist regime, combining the horrors of the historical precursors depicted so far. One aspect of these efforts by Project Democracy has involved the creation of an extensive and lawless invisible government, as has already been made clear in this report. But beyond all this, Project Democracy aims at definite changes in the structure of the government and institutions of the United States, of a kind so extensive that they could not be accomplished without a virtual obliteration of the Constitution. The starting point for this totalitarian plan was the Trilateral Commission, an organization created for the purpose of executing the policy of oligarchical and financier groupings making up the American, European, and Japanese branches of the banking elite. The Trilateral Commission was founded in the wake of Watergate and the oil crisis of 1973, events which the future Trilateral commissars had connived to create. One of the earliest projects of the Trilateral Commission was a study on the "ungovernability" of modern democracy in an era of economic crisis and social upheaval. This project was directed by Zbigniew Brzezinski, then the director of the Trilateral Commission. One of the results of this project that later came into the public domain was a book entitled The Crisis of Democracy by Michel Crozier, Samuel P. Huntington, and Joji Watanuki. It is to be assumed that the published version of this study and its appendices is a very diluted rendering of the discussions that went on among the rapporteurs and the Trilateral commissars. The Crisis of Democracy was a part of the agenda at the yearly meeting of the Trilateral Commission that took place in Tokyo, Japan on May 31, 1975. This was the same Trilateral meeting at which the former governor of Georgia, Jimmy Carter, was presented by FIAT chief Gianni Agnelli, and appointed by the commissars to be the next President of the United States. The starting point of The Crisis of Democracy is the collapse of such economic progress as had characterized the 1960s, and the advent of the post-industrial society. Brzezinski's introduction compares the atmosphere of 1975 with the early 1920s, when Oswald Spengler published his mystical Untergang des Abendlandes, or The Decline of the West. The three authors start off their analysis by quoting Willy Brandt, as he was about to step down as German Federal Chancellor in 1974, saying, "Western Europe has only 20 or 30 more years of democracy left in it; after that it will slide, engineless and rudderless, under the surrounding sea of dictatorship, and whether the dictation comes from a politburo or a junta will not make that much difference." Then there is a quote from an unnamed senior British official to the effect that if the United Kingdom fails to solve the problem of simultaneous inflation and economic depression, "parliamentary democracy would ultimately be replaced by a dictatorship." There is also a warning from Prime Minister Takeo Miki that "Japanese democracy will collapse" unless the confidence of the people in their political leaders can be restored. This is all related by the authors to the economic dimension of the crisis: This pessimism about the future of democracy has coincided with a parallel pessimism about the future of economic conditions. Economists have discovered the fifty-year Kondratieff cycle, according to which 1971 (like 1921) should have marked the beginning of a sustained economic downturn from which the industrialized capitalist world would not emerge until the end of the century. The implication is that just as the political developments of the 1920s and 1930s furnished the ironic and tragic aftermath of a war fought to make the world safe for democracy, so also the 1970s and 1980s might furnish a similarly ironic political aftermath to twenty years of sustained economic development designed in part to make the world prosperous enough for democracy. (pp. 2-3) Added to this obvious implication that economic depression would prove fatal to democratic forms by creating the necessary preconditions for fascist mass movements was the related idea that the United States Constitution could be overthrown in the aftermath of military defeat by the Soviet Union or perhaps by another power. The Trilateral meeting in question, it should be recalled, was taking place just a few weeks after the fall of Saigon. The Trilateral authors make this point as follows: "With the most active foreign policy of any democratic country, the United States is far more vulnerable to defeats in that area than other democratic governments, which, attempting less, also risk less. Given the relative decline in its military, economic, and political influence, the United States is more likely to face serious military or diplomatic reverses during the coming years than at any previous time in its history. If this does occur, it could pose a traumatic shock to American democracy." (p. 5) In addition to these crisis factors, the study also points to dynamics considered internal to the political process which are generating instability: "Yet, in recent years, the operations of the democratic process do indeed appear to have generated a breakdown of traditional means of social control, a de-legitimation of political and other forms of authority, and an overload of demands on government exceeding its capacity to respond." (p. 8) The study itself makes clear that the three Trilateral commissars are especially concerned about the economic demands made upon elected representatives by constituency groups which may contradict the austerity and primacy of debt service demanded by oligarchical financier factions. This theme dominates the chapter on the United States contributed by Samuel P. Huntington, who at various times has been a manager of the Harvard Center for International Affairs, the international network associated with Henry Kissinger. Huntington writes according to the canons of empirical social science, but the basic dictatorial intent nevertheless shines through. He describes the two great leaps in the expenditures of the U.S. federal government, the Defense Shift of the 1950s and the Welfare Shift of the1960s. He concludes that after these two shifts had vastly increased federal spending, the student revolt of the 1960s plus Watergate combined to produce "a substantial increase in government activity and a substantial decrease in governmental authority. By the early 1970s Americans were progressively demanding and receiving more benefits from their government and yet having less confidence in their government than they had a decade earlier." "The expansion of government activities produced doubts about the economic solvency of government; the decrease in governmental authority produced doubts about the political solvency of government." (p. 64) Reading ex contrario, it emerges that Huntington's ideal government would be an authoritarian regime capable of imposing drastic austerity. His problem is his despair that the U.S. government will fill the bill. Increased government spending is leading to high deficits, even as public confidence in government declines, says Huntington. He is especially concerned about the "decay of the party system," with the decline in clear party identification among the majority of the citizenry, the rise of split-ticket voting, and a decrease in party loyalty from one election to the next. As for the political parties themselves, Huntington's finding is that "the popular attitude towards parties combines both disapproval and contempt." (p. 87) Huntington also sees a decline in the mass base of the parties, plus a decline in the power of party organization. This raises the specter of a successful political challenge to the power of people like the members of Trilateral Commission: "The lesson of the 1960s was that American political parties were extraordinarily open and extraordinarily vulnerable organizations, in the sense that they could be easily penetrated, and even captured, by highly motivated and well-organized groups with a cause and a candidate." (p. 89) Huntington is willing to explore the alternative that the political parties may have to be done away with: "It could be argued that political parties are a political form peculiarly suited to the needs of industrial society and that the movement of the United States into a post-industrial phase hence means the end of the party system as we have known it." "In less developed countries, the principal alternative to party government is military government. Do the highly developed countries have a third alternative?" (p. 91) Huntington sees the entire government in crisis, with congressmen falling prey to the rising expectations of their constituents while the presidency is in decline. Part of the latter problem is that a presidential candidate needs to assemble an electoral coalition of voters in order to win the White House, but must then assemble a governing coalition of various power brokers. Huntington views the two processes as perhaps antithetical. The recommendations that conclude the analysis of the crisis in U.S. democracy include such pabulum as "moderation in democracy," more authoritarianism, and the need for greater apathy on the part of the population. "Democracy is more of a threat to itself in the United States," writes Huntington. The real conclusions reached by the Trilateral Commission were doubtless more far-reaching, as can be inferred from the appendices of the book. When the Crozier-Huntington-Watanuki study was presented to the commission, it was introduced by Ralf Dahrendorf, the head of the London School of Economics. The chief thread running through Dahrendorf's remarks was that Huntington had neglected corporatist elements in his prescription. Dahrendorf's argument deserves to be quoted at some length: Democratic governments find it difficult to cope with the power of extra-parliamentary institutions which determine by their decisions the life chances of as many (or in some cases more) people as the decisions of governments can possibly determine in many of our countries. Indeed, these extra-parliamentary institutions often make governmental power look ridiculous. When I talk about extra-parliamentary institutions, I am essentially thinking of two powerful economic institutions -- giant companies and large and powerful trade unions. The greater demand for participation, the removal of effective political spaces from the national to the international level, and the removal of the power to determine people's life chances from political institutions to other institutions are all signs of what might be called the dissolution of the general political public which we assumed was the basis of real democratic institutions in the past. Instead of there being an effective political public in democratic countries from which representative institutions emerge and to which representative institutions are answerable, there is a fragmented public and in part a nonexistent public. There is a rather chaotic picture in the political communities of many democratic countries. My main point here is that as we think about a political public in our day, we cannot simply think of a political public of individual citizens exercising their common sense interests on the marketplace, as it were. In rethinking the notion of the political public, we have to accept the fact that most human beings today are both individual citizens and members of large organizations. We have to accept the fact that most individuals see their interests cared for not only by an immediate expression of their citizenship rights (or even by political parties which organize groups of interests) but also by organizations which at this moment act outside the immediate political framework and which will continue to act whether governments like it or not. And I believe, therefore, somewhat reluctantly, that in thinking about the political public of tomorrow we shall have to think of a public in which representative parliamentary institutions are somehow linked with institutions which in themselves are neither representative nor parliamentary. I think it is useful to discuss the exact meaning of something like an effective social contract, or perhaps a "Concerted Action" or "Conseil economique et social" for the political institutions of advanced democracies. I do not believe that free collective bargaining is an indispensable element of a free and democratic society. I do believe, however, that we have to recognize that people are organized in trade unions, that there are large enterprises, that economic interests have got to be discussed somewhere, and that there has got to be a negotiation about some of the guidelines by which our economies are functioning. This discussion should be related to representative institutions. There may be a need for reconsidering some of our institutions in this light, not to convert our countries into corporate states, certainly not, but to convert them into countries which in a democratic fashion recognize some of the new developments which have made the effective political public so much less effective in recent years. For a reader who has followed the exposition up to this point, not much comment is necessary. Despite his very explicit disclaimer, Dahrendorf is indeed talking about a covert and overt institutional transformation toward a corporate state. We have seen several previous attempts to accomplish exactly what he is proposing here. One was D'Annunzio's Consiglio dei Provvisori, and another was Mussolini's Camera dei Fasci e delle Corporazioni. But the Trilateral Commission still needed a means of transition to corporatist rule. It was momentarily to propose it in the form of Project Democracy. The appendix to The Crisis of Democracy also contains a series of formal concluding statements by the Trilateral Commission at the close of debate on the ungovernability report. At a certain point, the text turns toward question of workers' self-management, co-determination (Mitbestimmung) as practiced in the Federal Republic of Germany, and the need for new modes of organization to alleviate the tensions that characterize post-industrial society. At that point, a new heading is introduced, as follows: "7. Creation of New Institution for the Cooperative Promotion of Democracy. The effective working of democratic government in the Trilateral societies can now no longer be taken for granted. The increasing demands and pressures on democratic government and the crisis in governmental resources and public authority require more explicit collaboration. One might consider, therefore, means of securing support and resources from foundations, business corporations, labor unions, political parties, civic associations, and, where possible and appropriate, government agencies, for the creation of an institute for the strengthening of democratic institutions. The purpose of such an institute would be to stimulate collaborative studies of common problems involved in the operations of democracy in the Trilateral societies, to promote cooperation among institutions and groups with common concerns in this area among the Trilateral regions, and to encourage the Trilateral societies to learn from each other's experience how to make democracy function more effectively in their societies. There is much which each society can learn from the others. Such mutual learning experiences are familiar phenomena in the economic and military fields; they must also be encouraged in the political field. Such an institute could also serve a useful function in calling attention to questions of special urgency, as, for instance, the critical nature of the problems currently confronting democracy in Europe." (p. 187) With that, Project Democracy was unleashed against the world. In the final discussion that followed Dahrendorf's remarks, the task of the new institute was made clearer. One participant suggested that Dahrendorf's idea of associating non-parliamentary groups with the parliamentary process ought to be seen in relation to international political systems, and not just in a national framework. At the close, "one Commissioner [Was it David Rockefeller?] expressed his support 'very concretely' for the proposed institute for the strengthening of democratic institutions." (p. 203) TRANSFORMING THE POLITICAL PARTIES Project Democracy is thus by pedigree an international fascist-corporatist organization designed to supplant democratic constitutional republics with veiled and overt fascist regimes. It is a kind of bankers' Comintern -- the Comintern of Bukharin, to be sure. As some of the citations adduced here suggest, it appears that one of the first tasks contemplated for the nascent Project Democracy network was the fomenting of coups d'etat in Western Europe, as was also indicated by abundant empirical evidence manifest at that time. What is the nature of Project Democracy's planned institutional transformation for the United States? Project Democracy intends to complete the evolution of the Republican and Democratic parties, especially the Democrats, away from their previous status as mass-based political machines responsive to the demands of constituencies and regional and local interests. Under the pretext of increasing the cohesion and responsibility of the parties, they are to acquire dictatorial control over the votes and opinions of elected officials, as for example, congressmen. The two parties are to become increasingly remote from the citizenry, and subjected to an increasingly authoritarian top-down control. Candidates are to become more and more like party functionaries, and are to be chosen by a tiny group of party leaders acting in synergy with the finance oligarchs. This will include presidential candidates most emphatically. Primary elections are to be gradually abolished in favor of a fascist-corporatist smoke-filled room. The specifically corporatist dimension of such a system in evolution from authoritarianism to totalitarianism is provided by the merger of the AFL-CIO top bureaucracy with the fused Democratic and Republican National Committees and fundraising apparatus. Despite the decline in the relative weight of trade unions in the U.S. workforce, the AFL-CIO is still by far the largest membership organization in the United States. This kind of troika is accurately reflected on the board of the National Endowment for Democracy. The AFL-CIO, by virtue of its close interfaces with the State Department, the Agency for International Development, the Labor Department, the Commerce Department, the Special Trade Representative, and the intelligence community, is virtually a government agency, precisely in the way that Bukharin wanted trade unions to be. By closely controlling the financing of candidates, access to the media, party endorsement, candidate debates, and the related election apparatus, the backers of Project Democracy think that they can in effect choose the Congress and choose the President. In this proposed silent putsch by Project Democracy, the RNC/DNC/AFL-CIO lockstep would acquire sovereignty over the U.S. federal government, in much the same way that the Soviet Politburo and Central Committee Secretariat control the Soviet Council of Ministers and Supreme Soviet. For Project Democracy, it is much more convenient for sovereignty to be located in an informal combine of private organizations, which cannot be subjected to government oversight, Freedom of Information Act demands, or financial audit and accountability, but which can and do receive large amounts of official government funding, as well as the largesse conduited through Oliver North's Swiss bank accounts. At the same time, Project Democracy is well aware of the value of maintaining a facade of respect for constitutional forms during the time in which the passage from authoritarianism to totalitarianism is being negotiated. It can be recalled that it took Mussolini some three years to go from head of the government to dictator, and still longer for the full institutional panoply of the totalitarian state to be set forth. In that transition, the suppression of opposition political groups and publishing enterprises was carried out gradually by squadristi and secret police. Today, these functions are assigned to the William Welds and the Oliver Revells. In the meantime, Project Democracy will find ways to denigrate and vilify the United States Constitution, even while going through the pretense of celebrating its anniversary. CORPORATIST PROPAGANDA In early 1975, Nicholas von Hoffman devoted his column in the Washington Post to revelations that certain prime financial supporters of the liberal wing of the Democratic Party have a "hidden agenda for American politics ... a planned economy ... state capitalism ... fascism without lampshade factories." Hoffman stated that the then-President of the United Auto Workers, Leonard Woodcock, was "willing to surrender the economic planning to the mega-corporations." In March 1975, Challenge magazine carried an article entitled "The Coming Corporatism," by R. E. Pahl and J. T. Winkler. The article stated in part: Corporatism is a distinct form of economic structure. It was recognized as such in the 1930s by people of diverse political backgrounds, before Hitler extinguished the enthusiasm which greeted Mussolini's variant. The fact that our blinkered political vocabulary now sees the alternative pure forms of economy as simply "capitalism" or "socialism" is a consequence of the fact that the Axis powers lost the Second World War. This "corporatism" is a comprehensive economic system under which the state intensively channels predominantly privately owned business towards four goals, which have become increasingly explicit during the current economic crisis: Order, Unity, Nationalism, and "Success." Those, then, are the four aims. Let us not mince words. Corporatism is fascism with a human face. What the parties are putting forward now is an acceptable face of fascism; indeed a masked version of it, because so far the more repugnant political and social aspects of the German and Italian regimes are absent or only present in diluted form. The same year saw the creation of an Initiative Committee for National Economic Planning with a press conference attended by Woodcock, Robert Roosa, and Wassily Leontieff. Among the sponsors of ICNEP were J. K. Galbraith and Robert McNamara. At the same time, officials of the Swedish, German, British, and Italian parties of the Second International were expressing the idea that, whereas in the last depression, the financiers had turned to fascist mass movements to impose corporatism and austerity, this time the social democrats could survive by showing that they were the most efficient agency for corporatist austerity. CORPORATISM IN THE 1988 PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN Signs are multiplying that with the present acceleration of economic collapse, corporatist agitation may become more widespread. One harbinger of such a trend is the highly ideologized presidential candidacy of former Arizona Gov. Bruce Babbitt. In declaring his candidacy for President, Babbitt proposed a "gain-sharing" plan under which he claimed that by 1996 "two-thirds of American workers would directly share in the profits and losses of their own business." When asked whether such a policy were not a return to corporatism, Babbitt answered that he preferred to call it "competitiveness" or "futurism," and later admitted that he was not sure of the meaning of corporatism. Babbitt's candidacy is designed to expose broad strata of the population to various parts of the Trilateral ideological inventory. The 1980 presidential candidacy of Trilateral Commission member Rep. John Anderson was also a vehicle for spewing out Malthusianism and anti-constitutional propaganda. Anderson's platform charged that despite the advent of post-industrial society, the Republicans and Democrats were still too "consumption-oriented." The platform stated: "The traditional parties were reasonably effective mechanisms for distributing the dividends of economic growth. But during a period in which the central task of government is to allocate burdens and orchestrate sacrifices, these parties have proved incapable of making the necessary hard choices. We are prepared to tell the American people what we must do, and allocate the burden in a manner sensitive to both economic efficiency and social equity." Babbitt's current rhetoric is strikingly similar. THE FUTURE: LOOKING TOWARDS THE UPSURGE OF 2010-2030 FROM 1981 Samuel Huntington, in his recent (1981) book American Politics, develops a perspective for the future development of the American political system in the framework of conflict between increasingly authoritarian and ultimately totalitarian state control, on the one hand, and an underlying American value system and world-outlook which he calls the "American Creed" on the other. In Huntington's view, there is no doubt that the regime will become more oppressive: "An increasingly sophisticated economy and active involvement in world affairs seem likely to create stronger needs for hierarchy, bureaucracy, centralization of power, expertise, big government specifically, and big organizations generally." (p. 228) But this will conflict with the ideological American Creed, based on liberty, equality, individualism, and democracy and rooted in "seventeenth-century Protestant moralism and eighteenth-century liberal rationalism." (p. 229) Something has to give, says Huntington. On the one hand, there is a possibility that the American Creed could be junked, and "there are some signs that values are changing." "In the 1960s and 1970s in both Europe and America, social scientists found evidence of the increasing prevalence of 'post-bourgeois' or 'post-materialist' values, particularly among younger cohorts. In a somewhat similar vein, George Lodge foresaw the displacement of Lockean, individualistic ideology in the United States by a 'communitarian' ideology, resembling in many aspects the traditional Japanese collective approach." Huntington predicts that the conflict between individualistic values and the centralized regime may explode early in the coming century specifically between 1010 and 2030, in a period of ferment and dislocation like the late 1960s: "If the periodicity of the past prevails, a major sustained creedal passion period will occur in the second and third decades of the twenty-first century." At this time, he argues, "the oscillations among the responses could intensify in such a way as to threaten to destroy both ideals and institutions." (p. 232) Such a process would be acted out as follows: Lacking any concept of the state, lacking for most of its history both the centralized authority and the bureaucratic apparatus of the European state, the American polity has historically been a weak polity. It was designed to be so, and the traditional inheritance and social environment combined for years to support the framers' intentions. In the twentieth century, foreign threats and domestic economic and social needs have generated pressures to develop stronger, more authoritative decision-making and decision-implementing institutions. Yet the continued presence of deeply felt moralistic sentiments among major groups in American society could continue to ensure weak and divided government, devoid of authority and unable to deal satisfactorily with the economic, social and foreign challenges confronting the nation. Intensification of this conflict between history and progress could give rise to increasing frustration and increasingly violent oscillations between moralism and cynicism. American moralism ensures that government will never be truly efficacious; the realities of power ensure that government will never be truly democratic. This situation could lead to a two-phase dialectic involving intensified efforts to reform government, followed by intensified frustration when those efforts produce not progress in a liberal-democratic direction, but obstacles to meeting perceived functional needs. The weakening of government in an effort to reform it could lead eventually to strong demands for the replacement of the weakened and ineffective institutions by more authoritarian structures more effectively designed to meet historical needs. Given the perversity of reform, moralistic extremism in the pursuit of liberal democracy could generate a strong tide toward authoritarian efficiency. (p. 232) Huntington then quotes Plato's celebrated passage on the way that the "culmination of liberty in democracy is precisely what prepares the way for the cruelest extreme of servitude under a despot." The message is clear: sooner or later, all roads lead to Behemoth. FASCISM AS AN AFTERMATH OF MILITARY DEFEAT Nous sommes trahis! cried the French in 1870 as they recoiled from defeat in war. For the Germans of 1918, it was the Dolchstosslegende, the stab in the back of the fighting army by the surrender of the politicians. For D'Annunzio and Mussolini, it was the vittoria mutilata, the inability of Orlando to impose Italy's territorial and colonial demands in the imperialist haggling of Versailles. Each of these reproaches, whatever their historical merits might have been, became vital factors in engendering mass fascist mentality and mass fascist movements. Parallels exist between such figures as Oliver North and the arditi who accompanied D'Annunzio to Fiume. According to former National Security Council director Robert McFarlane, "Lt. Col. Oliver North's experiences in the Vietnam War may have led him to secretly channel proceeds from the Iran arms sales to the Nicaraguan rebels while he was an NSC aide," according to an article published in the Washington Times in March 1987. The article quotes McFarlane, interviewed while recovering from a suicide attempt, as follows: "For people who went through that, and Colonel North surely did, you come away with the profound sense of very intolerable failure. That is, a government must never give its word to people who may stand to lose their lives and then break faith. And I think it's possible that in the last year we've seen a commitment made to human beings in Nicaragua that is being broken." As we have seen, the filibustering expedition of D'Annunzio to Fiume was a kind of dress rehearsal for Italian fascism. In post-World War I Germany, it was a similar kind of filibustering activity, the military campaigns of the Baltic Freikorps against the Bolsheviks, that created a significant part of the fascist potential which later aggregated in the Nazi Party. For the fascism of Project Democracy, the close historical parallel is the filibustering in Central America around the Contra war. _______________ Notes: 1. See Ralph H. Bowen, German Theories of the Corporate State, p. 2 2. Finer, Mussolini's Italy, p. 499 3. G. Lowell Field, The Syndical and Corporative Institutions of Italian Fascism, p. 137 A WEATHERMAN IN THE WHITEHOUSE? The Weather Underground terrorist cult was a largely successful operation of the left CIA to wreck the peace and student movements (SDS) after 1969. The cult's logo (above, on the cover of Bill Ayers' book) featured a rainbow with a lightning bolt. Does Obama's campaign logo (above) bear a strange resemblance? Obama is a close friend and neighbor of Weatherman terrorist bombers Bill Ayers and Bernardine Dohrn, who were rewarded with virtual immunity from prosecution and tenured professorships for their work as provocateurs. In 1995 they helped launch Obama's political career by hosting a fundraiser for his state senate campaign in their home. Obama and Ayers appeared at conferences together, and both were board members of the Woods Fund in Chicago until 2002. Above all, Obama worked for Ayers for eight years: Ayers was co-founder, organizer, and dominant personality of the Chicago Annenberg Challenge, a project for social engineering in the Chicago schools, where Obama served as Ayers' hand-picked chairman of the board from 1995-2003. -- WGT. The Weathermen were a countergang -- a group of provocateurs or hooligans that is inserted into a target group to discredit, destabilize and destroy it. The Weathermen logo may in turn be based on the logo and flag of the British Union of Fascists, or BUF (above) -- a white lightning stroke on a dark blue background, in a white circle, within an outer red circle or background. Oswald Mosley, the 1930's BUF leader, modeled his party of Blackshirts on Mussolini. He played a role in the "Hitler Project:" the installation of Nazism by the City of London and Wall Street, in order to bring about the mutual destruction of Germany and Russia, the two great European rivals of the century to Anglo-American hegemony. Research points to the conclusion that the Jacobins, Bolsheviks, Fascists and Nazis were all countergangs introduced by British Imperialism to debase rival nations. Above, top: The popular website Rense.com juxtaposed a jut-jawed image of Il Duce, the Fascist leader Mussolini, over an Obama campaign poster of similarly serious mien. Above, center: Hope and Change -- leitmotifs of Hitler's oratory, too -- revolutionary slogans to mobilize the masses of the world, now with Obama as keynote speaker on the U.S.-U.K. mass media megaphone. Will the ensuing uproar only take place in places that are targeted by the U.S.-U.K. for a Great Change to the worse, like Sudan, Pakistan, China and Russia? Interesting that China is hosting the Olympics, perfect occasion for a provocation. (Strange how Hitler got the games in 1936, too.) Will 2008 be the makings of another 1968, or 1848, when England was unscathed, while the rivals targeted by he revolutionary agents were all shaken to their timbers? Above bottom: Parody poster on the Internet, with the text: "It's an elitist thing -- you wouldn't understand." -- PP

|