CHAPTER IV.

THE PART WHICH WORMS HAVE PLAYED IN THE BURIAL OF ANCIENT

BUILDINGS.

The accumulation of rubbish on the

sites of great cities independent of the action of worms—The burial of a

Roman villa at Abinger—The floors and walls penetrated by

worms—Subsidence of a modern pavement—The buried pavement at Beaulieu

Abbey—Roman villas at Chedworth and Brading—The remains of the Roman

town at Silchester—The nature of the débris by which the remains are

covered—The penetration of the tesselated floors and walls by

worms—Subsidence of the floors—Thickness of the mould—The old Roman city

of Wroxeter—Thickness of the mould—Depth of the foundations of some of

the Buildings—Conclusion.

ARCHAEOLOGISTS are probably not aware how much they

owe to worms for the preservation of many ancient objects. Coins, gold

ornaments, stone implements, &c., if dropped on the surface of the

ground, will infallibly be buried by the castings of worms in a few

years, and will thus be safely preserved, until the land at some future

time is turned up. For instance, many years ago a grass-field was

ploughed on the northern side of the Severn, not far from Shrewsbury;

and a surprising number of iron arrow-heads were found at the bottom of

the furrows, which, as Mr. Blakeway, a local antiquary, believed, were

relics of the battle of Shrewsbury in the year 1403, and no doubt had

been originally left strewed on the battle-field. In the present chapter

I shall show that not only implements, &c., are thus preserved, but that

the floors and the remains of many ancient buildings in England have

been buried so effectually, in large part through the action of worms,

that they have been discovered in recent times solely through various

accidents. The enormous beds of rubbish, several yards in thickness,

which underlie many cities, such as Rome, Paris, and London, the lower

ones being of great antiquity, are not here referred to, as they have

not been in any way acted on by worms. When we consider how much matter

is daily brought into a great city for building, fuel, clothing and

food, and that in old times when the roads were bad and the work of the

scavenger was neglected, a comparatively small amount was carried away,

we may agree with Elie de Beaumont, who, in discussing this subject,

says, "pour une voiture de matériaux qui en sort, on y en fait entrer

cent." [1] Nor should we overlook the effects of fires, the demolition

of old buildings, and the removal of rubbish to the nearest vacant

space.

Abinger, Surrey.—Late

in the autumn of 1876, the ground in an old farm-yard at this place was

dug to a depth of 2 to 2½ feet, and the workmen found various ancient

remains. This led Mr. T. H. Farrer of Abinger Hall to have an adjoining

ploughed field searched. On a trench being dug, a layer of concrete,

still partly covered with tesseræ (small red tiles), and surrounded on

two sides by broken-down walls, was soon discovered. It is believed [2]

that this room formed part of the atrium or reception-room of a Roman

villa. The walls of two or three other small rooms were afterwards

discovered. Many fragments of pottery, other objects, and coins of

several Roman emperors, dating from 133 to 361, and perhaps to 375 A.D.,

were likewise found. Also a half-penny of George I., 1715. The presence

of this latter coin seems an anomaly; but no doubt it was dropped on the

ground during the last century, and since then there has been ample time

for its burial under a considerable depth of the castings of worms. From

the different dates of the Roman coins we may infer that the building

was long inhabited. It was probably ruined and deserted 1400 or 1500

years ago.

I was present during the commencement of the

excavations (August 20, 1877) and Mr. Farrer had two deep trenches dug

at opposite ends of the atrium, so that I might examine the nature of

the soil near the remains. The field sloped from east to west at an

angle of about 7°; and one of the two trenches, shown in the

accompanying section (Fig. 8) was at the upper or eastern end. The

diagram is on a scale of 1/20 of an inch to an inch; but the trench,

which was between 4 and 5 feet broad, and in parts above 5 feet deep,

has necessarily been reduced out of all proportion. The fine mould over

the floor of the atrium varied in thickness from 11 to 16 inches; and on

the side of the trench in the section was a little over 13 inches. After

the mould had been removed, the floor appeared as a whole moderately

level; but it sloped in parts at an angle of 1°, and in one place near

the outside at as much as 8° 30′· The wall surrounding the pavement was

built of rough stones, and was 23 inches in thickness where the trench

was dug. Its broken summit was here 13 inches, but in another part 15

inches, beneath the surface of the field, being covered by this

thickness of mould. In one spot, however, it rose to within 6 inches of

the surface. On two sides of the room, where the junction of the

concrete floor with the bounding walls could be carefully examined,

there was no crack or separation. This trench afterwards proved to have

been dug within an adjoining room (11 ft. by 11 ft. 6 in. in size), the

existence of which was not even suspected whilst I was present.

Fig. 8. Section through the

foundations of a buried Roman villa at Abinger. A A, vegetable mould; B,

dark earth full of stones, 13 inches in thickness; C, black mould; D,

broken mortar; E, black mould; F F, undisturbed sub-soil; G, tesseræ; H

concrete; I, nature unknown; W, buried wall.

On the side of the trench farthest from the buried

wall (W), the mould varied from 9 to 14 inches in thickness; it rested

on a mass (B) 23 inches thick of blackish earth, including many large

stones. Beneath this was a thin bed of very black mould (C), then a

layer of earth full of fragments of mortar (D), and then another thin

bed (about 3 inches thick) (F) of very black mould, which rested on the

undisturbed subsoil (F) of firm, yellowish, argillaceous sand. The

23-inch bed (B) was probably made ground, as this would have brought up

the floor of the room to a level with that of the atrium. The two thin

beds of black mould at the bottom of the trench evidently marked two

former land-surfaces. Outside the walls of the northern room, many

bones, ashes, oyster-shells, broken pottery and an entire pot were

subsequently found at a depth of 16 inches beneath the surface.

The second trench was dug on the western or lower side

of the villa: the mould was here only 6½ inches in thickness, and it

rested on a mass of fine earth full of stones, broken tiles and

fragments of mortar, 34 inches in thickness, beneath which was the

undisturbed sand. Most of this earth had probably been washed down from

the upper part of the field, and the fragments of stones, tiles, &c.,

must have come from the immediately adjoining ruins.

It appears at first sight a surprising fact that this

field of light sandy soil should have been cultivated and ploughed

during many years, and that not a vestige of these buildings should have

been discovered. No one even suspected that the remains of a Roman villa

lay hidden close beneath the surface. But the fact is less surprising

when it is known that the field, as the bailiff believed, had never been

ploughed to a greater depth than 4 inches. It is certain that when the

land was first ploughed, the pavement and the surrounding broken walls

must have been covered by at least 4 inches of soil, for otherwise the

rotten concrete floor would have been scored by the ploughshare, the

tesseræ torn up, and the tops of the old walls knocked down.

When the concrete and tesseræ were first cleared over

a space of 14 by 9 ft., the floor which was coated with trodden-down

earth exhibited no signs of having been penetrated by worms; and

although the overlying fine mould closely resembled that which in many

places has certainly been accumulated by worms, yet it seemed hardly

possible that this mould could have been brought up by worms from

beneath the apparently sound floor. It seemed also extremely improbable

that the thick walls, surrounding the room and still united to the

concrete, had been undermined by worms, and had thus been caused to

sink, being afterwards covered up by their castings. I therefore at

first concluded that all the fine mould above the ruins had been washed

down from the upper parts of the field; but we shall soon see that this

conclusion was certainly erroneous, though much fine earth is known to

be washed down from the upper part of the field in its present ploughed

state during heavy rains.

Although the concrete floor did not at first appear to

have been anywhere penetrated by worms, yet by the next morning little

cakes of the trodden-down earth had been lifted up by worms over the

mouths of seven burrows, which passed through the softer parts of the

naked concrete, or between the interstices of the tesseræ. On the third

morning twenty-five burrows were counted; and by suddenly lifting up the

little cakes of earth, four worms were seen in the act of quickly

retreating. Two castings were thrown up during the third night on the

floor, and these were of large size. The season was not favourable for

the full activity of worms, and the weather had lately been hot and dry,

so that most of the worms now lived at a considerable depth. In digging

the two trenches many open burrows and some worms were encountered at

between 30 and 40 inches beneath the surface; but at a greater depth

they became rare. One worm, however, was cut through at 48½, and another

at 51½ inches beneath the surface. A fresh humus-lined burrow was also

met with at a depth of 57 and another at 65½ inches. At greater depths

than this, neither burrows nor worms were seen.

As I wished to learn how many worms lived beneath the

floor of the atrium—a space of about 14 by 9 feet—Mr. Farrer was so kind

as to make observations for me, during the next seven weeks, by which

time the worms in the surrounding country were in full activity, and

were working near the surface. It is very improbable that worms should

have migrated from the adjoining field into the small space of the

atrium, after the superficial mould in which they prefer to live, had

been removed. We may therefore conclude that the burrows and the

castings which were seen here during the ensuing seven weeks were the

work of the former inhabitants of the space. I will now give a few

extracts from Mr. Farrer's notes.

Aug. 26th, 1877; that is, five days after the floor

had been cleared. On the previous night there had been some heavy rain,

which washed the surface clean, and now the mouths of forty burrows were

counted. Parts of the concrete were seen to be solid, and had never been

penetrated by worms, and here the rainwater lodged.

Sept. 5th.—Tracks of worms, made during the previous

night, could be seen on the surface of the floor, and five or six

vermiform castings had been thrown up. These were defaced.

Sept. 12th.—During the last six days, the worms have

not been active, though many castings have been ejected in the

neighbouring fields; but on this day the earth was a little raised over

the mouths of the burrows, or castings were ejected, at ten fresh

points. These were defaced. It should be understood that when a fresh

burrow is spoken of, this generally means only that an old burrow has

been re-opened. Mr. Farrer was repeatedly struck with the pertinacity

with which the worms re-opened their old burrows, even when no earth was

ejected from them. I have often observed the same fact, and generally

the mouths of the burrows are protected by an accumulation of pebbles,

sticks or leaves. Mr. Farrer likewise observed that the worms living

beneath the floor of the atrium often collected coarse grains of sand,

and such little stones as they could find, round the mouths of their

burrows.

Sept. 13th; soft wet weather. The mouths of the

burrows were re-opened, or castings were ejected, at 31 points; these

were all defaced.

Sept. 14th; 34 fresh holes or castings all defaced.

Sept. 15th; 44 fresh holes, only 5 castings; all

defaced.

Sept. 18th; 43 fresh holes, 8 castings; all defaced.

The number of castings on the surrounding fields was

now very large.

Sept. 19th; 40 holes, 8 castings; all defaced.

Sept. 22nd; 43 holes, only a few fresh castings; all

defaced.

Sept. 23rd; 44 holes, 8 castings.

Sept. 25th; 50 holes, no record of the number of

castings.

Oct. 13th; 61 holes, no record of the number of

castings.

After an interval of three years, Mr. Farrer, at my

request, again looked at the concrete floor, and found the worms still

at work.

Knowing what great muscular power worms possess, and

seeing how soft the concrete was in many parts, I was not surprised at

its having been penetrated by their burrows; but it is a more surprising

fact that the mortar between the rough stones of the thick walls,

surrounding the rooms, was found by Mr. Farrer to have been penetrated

by worms. On August 26th, that is, five days after the ruins had been

exposed, he observed four open burrows on the broken summit of the

eastern wall (W in Fig. 8); and, on September 15th, other burrows

similarly situated were seen. It should also be noted that in the

perpendicular side of the trench (which was much deeper than is

represented in Fig. 8) three recent burrows were seen, which ran

obliquely far down beneath the base of the old wall.

We thus see that many worms lived beneath the floor

and the walls of the atrium at the time when the excavations were made;

and that they afterwards almost daily brought up earth to the surface

from a considerable depth. There is not the slightest reason to doubt

that worms have acted in this manner ever since the period when the

concrete was sufficiently decayed to allow them to penetrate it; and

even before that period they would have lived beneath the floor, as soon

as it became pervious to rain, so that the soil beneath was kept damp.

The floor and the walls must therefore have been continually undermined;

and fine earth must have been heaped on them during many centuries,

perhaps for a thousand years. If the burrows beneath the floor and

walls, which it is probable were formerly as numerous as they now are,

had not collapsed in the course of time in the manner formerly

explained, the underlying earth would have been riddled with passages

like a sponge; and as this was not the case, we may feel sure that they

have collapsed. The inevitable result of such collapsing during

successive centuries, will have been the slow subsidence of the floor

and of the walls, and their burial beneath the accumulated

worm-castings. The subsidence of a floor, whilst it still remains nearly

horizontal, may at first appear improbable; but the case presents no

more real difficulty than that of loose objects strewed on the surface

of a field, which, as we have seen, become buried several inches beneath

the surface in the course of a few years, though still forming a

horizontal layer parallel to the surface. The burial of the paved and

level path on my lawn, which took place under my own observation, is an

analogous case. Even those parts of the concrete floor which the worms

could not penetrate would almost certainly have been undermined, and

would have sunk, like the great stones at Leith Hill Place and

Stonehenge, for the soil would have been damp beneath them. But the rate

of sinking of the different parts would not have been quite equal, and

the floor was not quite level. The foundations of the boundary walls

lie, as shown in the section, at a very small depth beneath the surface;

they would therefore have tended to subside at nearly the same rate as

the floor. But this would not have occurred if the foundations had been

deep, as in the case of some other Roman ruins presently to be

described.

Finally, we may infer that a large part of the fine

vegetable mould, which covered the floor and the broken-down walls of

this villa, in some places to a thickness of 16 inches, was brought up

from below by worms. From facts hereafter to be given there can be no

doubt that some of the finest earth thus brought up will have been

washed down the sloping surface of the field during every heavy shower

of rain. If this had not occurred a greater amount of mould would have

accumulated over the ruins than that now present. But beside the

castings of worms and some earth brought up by insects, and some

accumulation of dust, much fine earth will have been washed over the

ruins from the upper parts of the field, since it has been under

cultivation; and from over the ruins to the lower parts of the slope;

the present thickness of the mould being the resultant of these several

agencies.

I may here append a modern instance of the sinking of

a pavement, communicated to me in 1871 by Mr. Ramsay, Director of the

Geological Survey of England. A passage without a roof, 7 feet in length

by 3 feet 2 inches in width, led from his house into the garden, and was

paved with slabs of Portland stone. Several of these slabs were 16

inches square, others larger, and some a little smaller. This pavement

had subsided about 3 inches along the middle of the passage, and two

inches on each side, as could be seen by the lines of cement by which

the slabs had been originally joined to the walls. The pavement had thus

become slightly concave along the middle; but there was no subsidence at

the end close to the house. Mr. Ramsay could not account for this

sinking, until he observed that castings of black mould were frequently

ejected along the lines of junction between the slabs; and these

castings were regularly swept away. The several lines of junction,

including those with the lateral walls, were altogether 39 feet 2 inches

in length. The pavement did not present the appearance of ever having

been renewed, and the house was believed to have been built about

eighty-seven years ago. Considering all these circumstances, Mr. Ramsay

does not doubt that the earth brought up by the worms since the pavement

was first laid down, or rather since the decay of the mortar allowed the

worms to burrow through it, and therefore within a much shorter time

than the eighty-seven years, has sufficed to cause the sinking of the

pavement to the above amount, except close to the house, where the

ground beneath would have been kept nearly dry.

Beaulieu Abbey, Hampshire.—This

abbey was destroyed by Henry VIII., and there now remains only a portion

of the southern aisle-wall. It is believed that the king had most of the

stones carried away for building a castle; and it is certain that they

have been removed. The position of the nave-transept was ascertained not

long ago by the foundations having been found; and the place is now

marked by stones let into the ground. Where the abbey formerly stood,

there now extends a smooth grass-covered surface, which resembles in all

respects the rest of the field. The guardian, a very old man, said the

surface had never been levelled in his time. In the year 1853, the Duke

of Buccleuch had three holes dug in the turf within a few yards of one

another, at the western end of the nave; and the old tesselated pavement

of the abbey was thus discovered. These holes were afterwards surrounded

by brickwork, and protected by trap-doors, so that the pavement might be

readily inspected and preserved. When my son William examined the place

on January 5, 1872, he found that the pavement in the three holes lay at

depths of 6¾, 10 and 11½ inches beneath the surrounding turf-covered

surface. The old guardian asserted that he was often forced to remove

worm-castings from the pavement; and that he had done so about six

months before. My son collected all from one of the holes, the area of

which was 5·32 square feet, and they weighed 7·97 ounces. Assuming that

this amount had accumulated in six months, the accumulation during a

year on a square yard would be 1·68 pounds, which, though a large

amount, is very small compared with what, as we have seen, is often

ejected on fields and commons. When I visited the abbey on June 22,

1877, the old man said that he had cleared out the holes about a month

before, but a good many castings had since been ejected. I suspect that

he imagined that he swept the pavements oftener than he really did, for

the conditions were in several respects very unfavourable for the

accumulation of even a moderate amount of castings. The tiles are rather

large, viz., about 5½ inches square, and the mortar between them was in

most places sound, so that the worms were able to bring up earth from

below only at certain points. The tiles rested on a bed of concrete, and

the castings in consequence consisted in large part (viz., in the

proportion of 19 to 33) of particles of mortar, grains of sand, little

fragments of rock, bricks or tile; and such substances could hardly be

agreeable, and certainly not nutritious, to worms.

My son dug holes in several places within the former

walls of the abbey, at a distance of several yards from the above

described bricked squares. He did not find any tiles, though these are

known to occur in some other parts, but he came in one spot to concrete

on which tiles had once rested. The fine mould beneath the turf on the

sides of the several holes, varied in thickness from only 2 to 2¾

inches, and this rested on a layer from 8¾ to above 11 inches in

thickness, consisting of fragments of mortar and stone-rubbish with the

interstices compactly filled up with black mould. In the surrounding

field, at a distance of 20 yards from the abbey, the fine vegetable

mould was 11 inches thick.

We may conclude from these facts that when the abbey

was destroyed and the stones removed, a layer of rubbish was left over

the whole surface, and that as soon as the worms were able to penetrate

the decayed concrete and the joints between the tiles, they slowly

filled up the interstices in the overlying rubbish with their castings,

which were afterwards accumulated to a thickness of nearly three inches

over the whole surface. If we add to this latter amount the mould

between the fragments of stones, some five or six inches of mould must

have been brought up from beneath the concrete or tiles. The concrete or

tiles will consequently have subsided to nearly this amount. The bases

of the columns of the aisles are now buried beneath mould and turf. It

is not probable that they can have been undermined by worms, for their

foundations would no doubt have been laid at a considerable depth. If

they have not subsided, the stones of which the columns were constructed

must have been removed from beneath the former level of the floor.

Chedworth, Gloucestershire.—The

remains of a large Roman villa were discovered here in 1866, on ground

which had been covered with wood from time immemorial. No suspicion

seems ever to have been entertained that ancient buildings lay buried

here, until a gamekeeper, in digging for rabbits, encountered some

remains. [3] But subsequently the tops of some stone walls were detected

in parts of the wood, projecting a little above the surface of the

ground. Most of the coins found here belonged to Constans (who died 350

A.D.) and the Constantine family. My sons Francis and Horace visited the

place in November 1877, for the sake of ascertaining what part worms may

have played in the burial of these extensive remains. But the

circumstances were not favourable for this object, as the ruins are

surrounded on three sides by rather steep banks, down which earth is

washed during rainy weather. Moreover most of the old rooms have been

covered with roofs, for the protection of the elegant tesselated

pavements.

A few facts may, however, be given on the thickness of

the soil over these ruins. Close outside the northern rooms there is a

broken wall, the summit of which was covered by 5 inches of black mould;

and in a hole dug on the outer side of this wall, where the ground had

never before been disturbed, black mould, full of stones, 26 inches in

thickness, was found, resting on the undisturbed sub-soil of yellow

clay. At a depth of 22 inches from the surface a pig's jaw and a

fragment of a tile were found. When the excavations were first made,

some large trees grew over the ruins; and the stump of one has been left

directly over a party-wall near the bath room, for the sake of showing

the thickness of the superincumbent soil, which was here 38 inches. In

one small room, which, after being cleared out, had not been roofed

over, my sons observed the hole of a worm passing through the rotten

concrete, and a living worm was found within the concrete. In another

open room worm-castings were seen on the floor, over which some earth

had by this means been deposited, and here grass now grew.

Brading, Isle of Wight.—A

fine Roman villa was discovered here in 1880; and by the end of October

no less than 18 chambers had been more or less cleared. A coin dated

337 A.D. was found. My son William visited the place before the

excavations were completed; and he informs me that most of the floors

were at first covered with much rubbish and fallen stones, having their

interstices completely filled up with mould, abounding, as the workmen

said, with worms, above which there was mould without any stones. The

whole mass was in most places from 3 to above 4 ft. in thickness. In one

very large room the overlying earth was only 2 ft. 6 in. thick; and

after this had been removed, so many castings were thrown up between the

tiles that the surface had to be almost daily swept. Most of the floors

were fairly level. The tops of the broken-down walls were covered in

some places by only 4 or 5 inches of soil, so that they were

occasionally struck by the plough, but in other places they were covered

by from 13 to 18 inches of soil. It is not probable that these walls

could have been undermined by worms and subsided, as they rested on a

foundation of very hard red sand, into which worms could hardly burrow.

The mortar, however, between the stones of the walls of a hypocaust was

found by my son to have been penetrated by many worm-burrows. The

remains of this villa stand on land which slopes at an angle of about

3°; and the land appears to have been long cultivated. Therefore no

doubt a considerable quantity of fine earth has been washed down from

the upper parts of the field, and has largely aided in the burial of

these remains.

Silchester, Hampshire.—The

ruins of this small Roman town have been better preserved than any other

remains of the kind in England. A broken wall, in most parts from 15 to

18 feet in height and about 1½ mile in compass, now surrounds a space of

about 100 acres of cultivated land, on which a farm-house and a church

stand. [4] Formerly, when the weather was dry, the lines of the buried

walls could be traced by the appearance of the crops; and recently very

extensive excavations have been undertaken by the Duke of Wellington,

under the superintendence of the late Rev. J. G. Joyce, by which means

many large buildings have been discovered. Mr. Joyce made careful

coloured sections, and measured the thickness of each bed of rubbish,

whilst the excavations were in progress; and he has had the kindness to

send me copies of several of them. When my sons Francis and Horace

visited these ruins, he accompanied them, and added his notes to theirs.

Mr. Joyce estimates that the town was inhabited by the

Romans for about three centuries; and no doubt much matter must have

accumulated within the walls during this long period. It appears to have

been destroyed by fire, and most of the stones used in the buildings

have since been carried away. These circumstances are unfavourable for

ascertaining the part which worms have played in the burial of the

ruins; but as careful sections of the rubbish overlying an ancient town

have seldom or never before been made in England, I will give copies of

the most characteristic portions of some of those made by Mr. Joyce.

They are of too great length to be here introduced entire.

An east and west section, 30 ft. in length, was made

across a room in the Basilica, now called the Hall of the Merchants

(Fig. 9). The hard concrete floor, still covered here and there with

tesserae, was found at 3 ft.beneath the surface of the field, which was

here level. On the floor there were two large piles of charred wood, one

alone of which is shown in the part of the section here given. This pile

was covered by a thin white layer of decayed stucco or plaster, above

which was a mass, presenting a singularly disturbed appearance, of

broken tiles, mortar, rubbish and fine gravel, together 27 inches in

thickness. Mr. Joyce believes that the gravel was used in making the

mortar or concrete, which has since decayed, some of the lime probably

having been dissolved. The disturbed state of the rubbish may have been

due to its having been searched for building stones. This bed was capped

by fine vegetable mould, 9 inches in thickness. From these facts we may

conclude that the Hall was burnt down, and that much rubbish fell on the

floor, through and from which the worms slowly brought up the mould, now

forming the surface of the level field.

Fig. 9. Section within a room in the

Basilica at Silchester. Scale 1/18

A section across the middle of another hall in the

Basilica, 32 feet 6 inches in length, called the Œvarium, is shown in

Fig. 10. It appears that we have here evidence of two fires, separated

by an interval of time, during which the 6 inches of "mortar and

concrete with broken tiles" was accumulated. Beneath one of the layers

of charred wood, a valuable relic, a bronze eagle, was found; and this

shows that the soldiers must have deserted the place in a panic. Owing

to the death of Mr. Joyce, I have not been able to ascertain beneath

which of the two layers the eagle was found. The bed of rubble overlying

the undisturbed gravel originally formed, as I suppose, the floor, for

it stands on a level with that of a corridor, outside the walls of the

Hall; but the corridor is not shown in the section as here given. The

vegetable mould was 16 inches thick in the thickest part; and the depth

from the surface of the field, clothed with herbage, to the undisturbed

gravel, was 40 inches.

Fig. 10. Section within a hall

in the Basilica at Silchester. Scale 1/32.

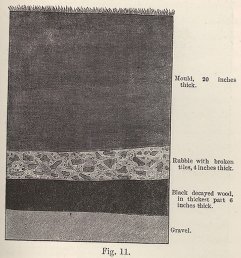

The section shown in Fig. 11 represents an excavation

made in the middle of the town, and is here introduced because the bed

of "rich mould" attained, according to Mr. Joyce, the unusual thickness

of 20 inches. Gravel lay at the depth of 48 inches from the surface; but

it was not ascertained whether this was in its natural state, or had

been brought here and had been rammed down, as occurs in some other

places.

The section shown in Fig. 12 was taken in the centre

of the Basilica, and though it was 5 feet in depth, the natural sub-soil

was not reached. The bed marked "concrete" was

probably at one time a floor; and the beds beneath seem to be the

remnants of more ancient buildings. The vegetable mould was here only 9

inches thick. In some other sections, not copied, we likewise have

evidence of buildings having been erected over the ruins of older ones.

In one case there was a layer of yellow clay of very unequal thickness

between two beds of débris, the lower one of which rested on a floor

with tesserae. The old broken walls appear sometimes to have been

roughly cut down to a uniform level, so as to serve as the foundations

of a temporary building; and Mr. Joyce suspects that some of these

buildings were wattled sheds, plastered with clay, which would account

for the above-mentioned layer of clay.

Fig. 11. Section in a block of

buildings in the middle of the town of Silchester.

Fig. 12. Section in the centre

of the Basilica at Silchester.

Turning now to the points which more immediately

concern us. Worm-castings were observed on the floors of several of the

rooms, in one of which the tesselation was unusually perfect. The

tesseræ here consisted of little cubes of hard sandstone of about 1

inch, several of which were loose or projected slightly above the

general level. One or occasionally two open worm-burrows were found

beneath all the loose tesseræ. Worms have also penetrated the old walls

of these ruins. A wall, which had just been exposed to view during the

excavations then in progress, was examined; it was built of large

flints, and was 18 inches in thickness.

It appeared sound, but when the soil was removed from

beneath, the mortar in the lower part was found to be so much decayed

that the flints fell apart from their own weight. Here, in the middle of

the wall, at a depth of 29 inches beneath the old floor and of 49½

inches beneath the surface of the field, a living worm was found, and

the mortar was penetrated by several burrows.

A second wall was exposed to view for the first time,

and an open burrow was seen on its broken summit. By separating the

flints this burrow was traced far down in the interior of the wall; but

as some of the flints cohered firmly, the whole mass was disturbed in

pulling down the wall, and the burrow could not be traced to the bottom.

The foundations of a third wall, which appeared quite sound, lay at a

depth of 4 feet beneath one of the floors, and of course at a

considerably greater depth beneath the level of the ground. A large

flint was wrenched out of the wall at about a foot from the base, and

this required much force, as the mortar was sound; but behind the flint

in the middle of the wall, the mortar was friable, and here there were

worm-burrows. Mr. Joyce and my sons were surprised at the blackness of

the mortar in this and in several other cases, and at the presence of

mould in the interior of the walls. Some may have been placed there by

the old builders instead of mortar; but we should remember that worms

line their burrows with black humus. Moreover open spaces would almost

certainly have been occasionally left between the large irregular

flints; and these spaces, we may feel sure, would be filled up by the

worms with their castings, as soon as they were able to penetrate the

wall. Rain-water, oozing down the burrows would also carry fine dark-coloured

particles into every crevice. Mr. Joyce was at first very sceptical

about the amount of work which I attributed to worms; but he ends his

notes with reference to the last-mentioned wall by saying, "This case

caused me more surprise and brought more conviction to me than any

other. I should have said, and did say, that it was quite impossible

such a wall could have been penetrated by earth-worms."

In almost all the rooms the pavement has sunk

considerably, especially towards the middle; and this is shown in the

three following sections. The measurements were made by stretching a

string tightly and horizontally over the floor. The section, Fig. 13,

was taken from north to south across a room, 18 feet 4 inches in length,

with a nearly perfect pavement, next to the "Red Wooden Hut." In the

northern half, the subsidence amounted to 5¾ inches beneath the level of

the floor as it now stands close to the walls; and it was greater in the

northern than in the southern half; but, according to Mr. Joyce, the

entire pavement has obviously subsided. In several places, the tesseræ

appeared as if drawn a little away from the walls; whilst in other

places they were still in close contact with them.

Fig. 13. Section of the

subsided floor of a room, paved with tesserae, at Silchester. Scale

1/40.

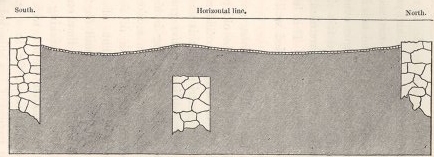

In Fig. 14, we see a section across the paved floor of

the southern corridor or ambulatory of a quadrangle, in an excavation

made near "The Spring." The floor is 7 feet 9 inches wide, and the

broken-down walls now project only ¾ of an inch above its level. The

field, which was in pasture, here sloped from north to south, at an

angle of 3° 40′. The nature of the ground on each side of the corridor

is shown in the section. It consisted of earth full of stones and other

débris, capped with dark vegetable mould which was thicker on the lower

or southern than on the northern side. The pavement was nearly level

along lines parallel to the side-walls, but had sunk in the middle as

much as 7¾ inches.

A small room at no great distance from that

represented in Fig. 13, had been enlarged by the Roman occupier on the

southern side, by an addition of 5 feet 4 inches in breadth. For this

purpose the southern wall of the house had been pulled down, but the

foundations of the old wall had been left buried at a little depth

beneath the pavement of the enlarged room. Mr. Joyce believes that this

buried wall must have been built before the reign of Claudius II., who

died 270, A.D. We see in the accompanying section, Fig. 15, that the

tesselated pavement has subsided to a less degree over the buried wall

than elsewhere; so that a slight convexity or protuberance here

stretched in a straight line across the room. This led to a hole being

dug, and the buried wall was thus discovered.

Fig. 14. A north and south

section through the subsided floor of a corridor, paved with tesseræ.

Outside the broken-down bounding walls, the excavated ground on each

side is shown for a short space. Nature of the ground beneath the

tesseræ unknown. Silchester. Scale 1/36.

We see in these three sections, and in several others

not given, that the old pavements have sunk or sagged considerably. Mr.

Joyce formerly attributed this sinking solely to the slow settling of

the ground. That there has been some settling is highly probable, and it

may be seen in section 15 that the pavement for a width of 5 feet over

the southern enlargement of the room, which must have been built on

fresh ground, has sunk a little more than on the old northern side. But

this sinking may possibly have had no connection with the enlargement of

the room, for in Fig. 13, one half of the pavement has subsided more

than the other half without any assignable cause. In a bricked passage

to Mr. Joyces own house, laid down only about six years ago, the same

kind of sinking has occurred as in the ancient buildings. Nevertheless

it does not appear probable that the whole amount of sinking can be thus

accounted for. The Roman builders excavated the ground to an unusual

depth for the foundations of their walls, which were thick and solid; it

is therefore hardly credible that they should have been careless about

the solidity of the bed on which their tesselated and often ornamented

pavements were laid. The sinking must, as it appears to me, be

attributed in chief part to the pavement having been undermined by

worms, which we know are still at work. Even Mr. Joyce at last admitted

that this could not have failed to have produced a considerable effect.

Thus also the large quantity of fine mould overlying the pavements can

be accounted for, the presence of which would otherwise be inexplicable.

My sons noticed that in one room in which the pavement had sagged very

little, there was an unusually small amount of overlying mould.

Fig. 15. Section of the

subsided floor, paved with tessarae, and of the broken-down bounding

walls of a room at Silchester, which had been formerly enlarged, with

the foundations of the old wall left buried. Scale 1/40.

As the foundations of the walls generally lie at a

considerable depth, they will either have not subsided at all through

the undermining action of worms, or they will have subsided much less

than the floor. This latter result would follow from worms not often

working deep down beneath the foundations; but more especially from the

walls not yielding when penetrated by worms, whereas the successively

formed burrows in a mass of earth, equal to one of the walls in depth

and thickness, would have collapsed many times since the desertion of

the ruins, and would consequently have shrunk or subsided. As the walls

cannot have sunk much or at all, the immediately adjoining pavement from

adhering to them will have been prevented from subsiding; and thus the

present curvature of the pavement is intelligible.

The circumstance which has surprised me most with

respect to Silchester is that during the many centuries which have

elapsed since the old buildings were deserted, the vegetable mould has

not accumulated over them to a greater thickness than that here

observed. In most places it is only about 9 inches in thickness, but in

some places 12 or even more inches. In Fig. 11, it is given as 20

inches, but this section was drawn by Mr. Joyce before his attention was

particularly called to this subject. The land enclosed within the old

walls is described as sloping slightly to the south; but there are parts

which, according to Mr. Joyce, are nearly level, and it appears that the

mould is here generally thicker than elsewhere. The surface slopes in

other parts from west to east, and Mr. Joyce describes one floor as

covered at the western end by rubbish and mould to a thickness of 28½

inches, and at the eastern end by a thickness of only 11½ inches. A very

slight slope suffices to cause recent castings to flow downwards during

heavy rain, and thus much earth will ultimately reach the neighbouring

rills and streams and be carried away. By this means, the absence of

very thick beds of mould over these ancient ruins may, as I believe, be

explained. Moreover most of the land here has long been ploughed, and

this would greatly aid the washing away of the finer earth during rainy

weather.

The nature of the beds immediately beneath the

vegetable mould in some of the sections is rather perplexing. We see,

for instance, in the section of an excavation in a grass meadow (Fig.

14), which sloped from north to south at an angle of 3° 40′, that the

mould on the upper side is only six inches and on the lower side nine

inches in thickness. But this mould lies on a mass (25½ inches in

thickness on the upper side) "of dark brown mould," as described by Mr.

Joyce, "thickly interspersed with small pebbles and bits of tiles, which

present a corroded or worn appearance." The state of this dark-coloured

earth is like that of a field which has long been ploughed, for the

earth thus becomes intermingled with stones and fragments of all kinds

which have been much exposed to the weather. If during the course of

many centuries this grass meadow and the other now cultivated fields

have been at times ploughed, and at other times left as pasture, the

nature of the ground in the above section is rendered intelligible. For

worms will continually have brought up fine earth from below, which will

have been stirred up by the plough whenever the land was cultivated. But

after a time a greater thickness of fine earth will thus have been

accumulated than could be reached by the plough; and a bed like the

25½-inch mass, in Fig. 14, will have been formed beneath the superficial

mould, which latter will have been brought to the surface within more

recent times, and have been well sifted by the worms.

Wroxeter, Shropshire.—The

old Roman city of Uriconium was founded in the early part of the second

century, if not before this date; and it was destroyed, according to Mr.

Wright, probably between the middle of the fourth and fifth century. The

inhabitants were massacred, and skeletons of women were found in the

hypocausts. Before the year 1859, the sole remnant of the city above

ground, was a portion of a massive wall about 20 ft. in height. The

surrounding land undulates slightly, and has long been under

cultivation. It had been noticed that the corn-crops ripened prematurely

in certain narrow lines, and that the snow remained unmelted in certain

places longer than in others.

These appearances led, as I was informed, to extensive

excavations being undertaken. The foundations of many large buildings

and several streets have thus been exposed to view. The space enclosed

within the old walls is an irregular oval, about 1¾ mile in length. Many

of the stones or bricks used in the buildings must have been carried

away; but the hypocausts, baths, and other underground buildings were

found tolerably perfect, being filled with stones, broken tiles, rubbish

and soil. The old floors of various rooms were covered with rubble. As I

was anxious to know how thick the mantle of mould and rubbish was, which

had so long concealed these ruins, I applied to Dr. H. Johnson, who had

superintended the excavations; and he, with the greatest kindness, twice

visited the place to examine it in reference to my questions, and had

many trenches dug in four fields which had hitherto been undisturbed.

The results of his observations are given in the following Table. He

also sent me specimens of the mould, and answered, as far as he could,

all my questions.

MEASUREMENTS BY DR. H. JOHNSON OF THE THICKNESS OF

THE VEGETABLE MOULD OVER THE ROMAN RUINS AT WROXETER.

Trenches dug in a field called "Old Works."

| |

|

Thickness

of mould in inches. |

| 1. |

At a depth of 36 inches

undisturbed sand was reached .. .. .. .. .. |

20 |

| 2. |

At a depth of 33 inches

concrete was reached |

21 |

| 3. |

At a depth of 9 inches

concrete was reached |

9 |

Trenches dug in a field called "Shop Leasows;" this is

the highest field within the old walls, and slopes down from a

sub-central point on all sides at about an angle of 2.

| |

|

Thickness

of mould in inches. |

| 4. |

Summit of field, trench 45

inches deep .. |

40 |

| 5. |

Close to summit of field,

trench 36 inches deep |

26 |

| 6. |

Close to summit of field,

trench 28 inches deep |

28 |

| 7. |

Near summit of field, trench

36 inches deep |

24 |

| 8. |

Near summit of field, trench at one end

39 inches deep; the mould here graduated into the underlying

undisturbed sand, and its thickness is somewhat arbitrary.

At the other end of the trench, a causeway was encountered

at a depth of only 7 inches, and the mould was here only 7

inches thick .. |

24 |

| 9. |

Trench close to the last, 28

inches in depth .. |

15 |

| 10. |

Lower part of same field,

trench 30 inches deep |

15 |

| 11. |

Lower part of same field,

trench 31 inches deep |

17 |

| 12. |

Lower part of same field,

trench 36 inches deep, at which depth undisturbed sand was

reached |

28 |

| 13. |

In another part of same

field, trench 9½ inches deep, stopped by concrete .. .. .. |

9½ |

| 14. |

In another part of same

field, trench 9 inches deep, stopped by concrete .. .. .. |

9 |

| 15. |

In another part of the same

field, trench 24 inches deep, when sand was reached .. |

16 |

| 16. |

In another part of same

field, trench 30 inches deep, when stones were reached; at

one end of the trench mould 12 inches, at the other end 14

inches thick .. .. .. .. |

13 |

Small field between "Old Works" and "Shop Leasows," I

believe nearly as high as the upper part of the latter field.

| |

|

Thickness

of mould in inches. |

| 17. |

Trench 26 inches deep .. ..

.. |

24 |

| 18. |

Trench 10 inches deep, and

then came upon a causeway .. .. .. .. .. |

10 |

| 19. |

Trench 34 inches deep .. ..

.. |

30 |

| 20. |

Trench 31 inches deep.. ..

.. .. |

31 |

Field on the western side of the space enclosed within

the old walls.

| |

|

Thickness

of mould in inches. |

| 21. |

Trench 28 inches deep, when

undisturbed sand was reached .. .. .. .. .. |

16 |

| 22. |

Trench 29 inches deep, when

undisturbed sand was reached .. .. .. .. .. |

15 |

| 23. |

Trench 14 inches deep, and

then came upon a building .. .. .. .. .. |

14 |

Dr. Johnson distinguished as mould the earth which

differed, more or less abruptly, in its dark colour and in its texture

from the underlying sand or rubble. In the specimens sent to me, the

mould resembled that which lies immediately beneath the turf in old

pasture-land, excepting that it often contained small stones, too large

to have passed through the bodies of worms. But the trenches above

described were dug in fields, none of which were in pasture, and all had

been long cultivated. Bearing in mind the remarks made in reference to

Silchester on the effects of long-continued culture, combined with the

action of worms in bringing up the finer particles to the surface, the

mould, as so designated by Dr. Johnson, seems fairly well to deserve its

name. Its thickness, where there was no causeway, floor or walls

beneath, was greater than has been elsewhere observed, namely in many

places above 2 ft., and in one spot above 3 ft. The mould was thickest

on and close to the nearly level summit of the field called "Shop

Leasows," and in a small adjoining field, which, as I believe, is of

nearly the same height. One side of the former field slopes at an angle

of rather above 2°, and I should have expected that the mould, from

being washed down during heavy rain, would have been thicker in the

lower than in the upper part; but this was not the case in two out of

the three trenches here dug.

In many places, where streets ran beneath the surface,

or where old buildings stood, the mould was only 8 inches in thickness;

and Dr. Johnson was surprised that in ploughing the land, the ruins had

never been struck by the plough as far as he had heard. He thinks that

when the land was first cultivated the old walls were perhaps

intentionally pulled down, and that hollow places were filled up. This

may have been the case; but if after the desertion of the city the land

was left for many centuries uncultivated, worms would have brought up

enough fine earth to have covered the ruins completely; that is if they

had subsided from having been undermined. The foundations of some of the

walls, for instance those of the portion still standing about 20 feet

above the ground, and those of the market-place, lie at the

extraordinary depth of 14 feet; but it is highly improbable that the

foundations were generally so deep. The mortar employed in the buildings

must have been excellent, for it is still in parts extremely hard.

Where-ever walls of any height have been exposed to view, they are, as

Dr. Johnson believes, still perpendicular. The walls with such deep

foundations cannot have been undermined by worms, and therefore cannot

have subsided, as appears to have occurred at Abinger and Silchester.

Hence it is very difficult to account for their being now completely

covered with earth; but how much of this covering consists of vegetable

mould and how much of rubble I do not know. The market-place, with the

foundations at a depth of 14 feet, was covered up, as Dr. Johnson

believes, by between 6 and 24 inches of earth. The tops of the

broken-down walls of a caldarium or bath, 9 feet in depth, were likewise

covered up with nearly 2 feet of earth. The summit of an arch, leading

into an ash-pit 7 feet in depth, was covered up with not more than 8

inches of earth. Whenever a building which has not subsided is covered

with earth, we must suppose, either that the upper layers of stone have

been at some time carried away by man, or that earth has since been

washed down during heavy rain, or blown down during storms, from the

adjoining land; and this would be especially apt to occur where the land

has long been cultivated. In the above cases the adjoining land is

somewhat higher than the three specified sites, as far as I can judge by

maps and from information given me by Dr. Johnson. If, however, a great

pile of broken stones mortar, plaster, timber and ashes fell over the

remains of any building, their disintegration in the course of time, and

the sifting action of worms, would ultimately conceal the whole beneath

fine earth.

Conclusion.—The cases

given in this chapter show that worms have played a considerable part in

the burial and concealment of several Roman and other old buildings in

England; but no doubt the washing down of soil from the neighbouring

higher lands, and the deposition of dust, have together aided largely in

the work of concealment. Dust would be apt to accumulate wherever old

broken-down walls projected a little above the then existing surface and

thus afforded some shelter. The floors of the old rooms, halls and

passages have generally sunk, partly from the settling of the ground,

but chiefly from having been undermined by worms; and the sinking has

commonly been greater in the middle than near the walls. The walls

themselves, whenever their foundations do not lie at a great depth, have

been penetrated and undermined by worms, and have consequently subsided.

The unequal subsidence thus caused, probably explains the great cracks

which may be seen in many ancient walls, as well as their inclination

from the perpendicular.

_______________

1. 'Leçons de Géologie pratique, 1845,

p. 142.

2. A short account of this discovery

was published in 'The Times of January 2, 1878; and a fuller account in

'The Builder, January 5, 1878.

3. Several accounts of these

ruins have been published; the best is by Mr. James Farrer in 'Proc.

Soc. of Antiquaries of Scotland,' vol. vi., Part II., 1867, p. 278. Also

J. W. Grover, 'Journal of the British Arch. Assoc.' June 1866. Professor

Buckman has likewise published a pamphlet, 'Notes on the Roman Villa at

Chedworth,' 2nd edit. 1873: Cirencester.

4. These details are taken from

the 'Penny Encyclopædia,' article, Hampshire.