|

BLACK EASTER -- THREE SLEEPS |

|

VI Father Domenico's interview with Theron Ware was brief, formal and edgy. The monk, despite his apprehensions, had been curious to see what the magician looked like, and had been irrationally disappointed -- to find him not much out of the ordinary run of intellectuals. Except for the tonsure, of course; like Baines, Father Domenico found that startling. Also, unlike Baines, he found it upsetting, because he knew the reason for it -- not that Ware intended any mockery of his pious counterparts, but because demons, given a moment of inattention, were prone to seizing one by the hair. "Under the Covenant," Ware told him in excellent Latin, "l have no choice but to receive you, of course, Father. And under other circumstances I might even have enjoyed discussing the Art with you, even though we are of opposite schools. But this is an inconvenient time for me. I've got a very important client here, as you've seen, and I've already been notified that what he wants of me is likely to be extraordinarily ambitious." "I shan't interfere in any way," Father Domenico said. "Even should I wish to, which obviously I shall, I know very well that any such interference would cost me all my protections." "I was sure you understood that, but nonetheless I'm glad to hear you say so," Ware said. "However, your very presence here is an embarrassment -- not only because I'll have to explain it to my client, but also because it changes the atmosphere unfavorably and will make my operations more difficult. I can only hope, in defiance of all hospitality, that your mission will be speedily satisfied." "I can't bring myself to regret the difficulty, since I only wish I could make your operations outright impossible. The best I can proffer you is strict adherence to the truce. As for the length of my stay, that depends wholly on what it is your client turns out to want, and how long that takes. I am charged with seeing it through to its conclusion." "A prime nuisance," Ware said. "I suppose I should be grateful that I haven't been blessed with this kind of attention from Monte Albano before. Evidently what Mr. Baines intends is even bigger than he thinks it is. I conclude without much cerebration that you know something about it I don't know." "It will be an immense disaster, I can ten you that." "Hmm. From your point of view, but not necessarily from mine, possibly. I don't suppose you're prepared to offer any further information -- on the chance, say, of dissuading me?" "Certainly not," Father Domenico said indignantly. "If eternal damnation hasn't dissuaded you long before this, I'd be a fool to hope to." "Well," Ware said, "but you are, after all, charged with the cure of souls, and unless the Church has done another flipflop since the last Congress, it is still also a mortal sin to assume that any man is certainly damned -- even me." That argument was potent, it had to be granted; but Father Domenico had not been trained in casuistry (and that by Jesuits) for nothing. "I'm a monk, not a priest," he said. "And "any information I give you would, on the contrary, almost certainly be used to abet the evil, not turn it aside. I don't find the choice a hard one under the circumstances." "Then let me suggest a more practical consideration," Ware said. "I don't know yet what Baines intends, but I do know well enough that I am not a Power myself -- only a fautor. I have no desire to bite off more than I can chew." "Now you're just wheedling," Father Domenico said, with energy. "Knowing

your own limitations is not an exercise at which I or anyone else can help

you. You'll just have to weigh them in the light of Mr. Baines'

commission, whatever that proves to be. In the meantime, I shall tell you

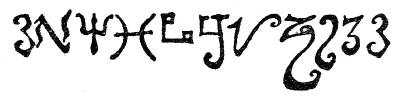

"Very well," Ware said, rising. "I will be a little more generous with my information, Father, than you have been with yours. I will tell you that you will be well advised to adhere to every letter of the Covenant. One step over the line, one toe, and I shall have you -- and hardly any outcome in this world would give me greater pleasure. I'm sure I make myself clear." Father Domenico could think of no reply; but none seemed to be necessary. VII As Ware had sensed, Baines was indeed disturbed by the presence of Father Domenico, and made a point of bringing it up as the first order of business. After Ware had explained the monk's mission and the Covenant under which it was being conducted, however, Baines felt somewhat relieved. "Just a nuisance, as you say, since he can't actually intervene," he decided. "In a way, I suppose my bringing Dr. Hess here with me is comparable -- he's only an observer, too, and fundamentally he's probably just as hostile to your world-view as this holier-than-us fellow is." "He's not significantly holier than us," Ware said with a slight smile. "I know something he doesn't know, too. He's in for a surprise in the next world. However, for the time being we're stuck with him -- for how long depends upon you. Just what is it you want this time, Dr. Baines?" "Two things, one depending on the other. The first is the death of Albert Stockhausen." "The anti-matter theorist? That would be too bad. I rather like him, and besides, some of the work he does is of direct interest to me." "You refuse?" "No, not immediately anyhow, but I'm now going to ask you what I promised I would ask on this occasion. What are you aiming at, anyhow?" "Something very long-term. For the present, my lethal intentions for Dr. Stockhausen are strictly business-based. He's nibbling at the edges of a scholium that my company presently controls completely. It's a monopoly of knowledge we don't want to see broken." "Do you think you can keep anything secret that's based in natural law? After the McCarthy fiasco I should have supposed that any intelligent American would know better. Surely Dr. Stockhausen can't be just verging on some mere technicality -- something your firm might eventually bracket with a salvo of process patents." "No, it's in the realm of natural law, and hence not patentable at all," Baines admitted. "And we already know that it can't be concealed forever. But we need about five years' grace to make the best use of it, and we know that nobody else but Stockhausen is even close to it, barring accidents, of course. We ourselves have nobody of Stockhausen's caliber, we just fell over it, and somebody else might do that. However, that's highly unlikely." "I see. Well ... the project does have an attractive side. I think it's quite possible that I can persuade Father Domenico that this is the project he came to observe. Obviously it can't be -- I've run many like it and never attracted Monte Albano's interest to this extent before -- but given sufficient show of great preparations, and difficulty of execution, he might be deluded, and go home." "That would be useful," Baines agreed. "The question is, could he be deceived?" "It's worth trying. The task would in fact be difficult -- and quite expensive." "Why?" Jack Ginsberg said, sitting bolt upright in his carved Florentine chair so suddenly as to make his suit squeak against the silk upholstery. "Don't tell us he affects thousands of other people. Nobody ever cast any votes for him that I know of." "Shut up, Jack." "No, wait, it's a reasonable question," Ware said. "Dr. Stockhausen does have a large family, which I have to take into account. And, as I've told you, I've taken some pleasure in his company on a few occasions -- not enough to balk at having him sent for, but enough to help run up the price. "But that's not the major impediment. The fact is that Dr. Stockhausen like a good many theoretical physicists these days, is a devout man -- and furthermore, he has only a few venial sins to account for, nothing in the least meriting the attention of Hell. I'll check that again with Someone who knows, but it was accurate as of six months ago and I'd be astonished if there's been any change. He's not a member of any formal congregation, but even so he's nobody a demon could reasonably have come for him -- and there's a chance that he might be defended against any direct assault." "Successfully?" "It depends on the forces involved. Do you want to risk a pitched battle that would tear up half of Dusseldorf? It might be cheaper just to mail him a bomb." "No, no. And I don't want anything that might look like some kind of laboratory accident -- that'd be just the kind of clue that would set everybody else in his field haring after what we want to keep hidden. The whole secret lies in the fact that once Stockhausen knows what we know, he could create a major explosion with -- well, with the equivalent of a blackboard and two pieces of chalk. Isn't there any other way?" "Men being men, there's always another way. In this instance, though, I'd have to have him tempted. I know at least one promising avenue. But he might not fall. And even if he did, as I think he would, it would take several months and a lot of close monitoring. Which wouldn't be altogether intolerable either, since it would greatly help to mislead Father Domenico. "What would it cost?" Jack Ginsberg said. "Oh -- say about eight million. Entirely a contingent fee this time, since I can't see that there'd be any important out-of-pocket money needed. If there is, I'll absorb it." "That's nice," Jack said. Ware took no notice of the feeble sarcasm. Baines put on his adjudicative face, but inwardly he was well satisfied. As a further test, the death of Dr. Stockhausen was not as critical as that of Governor Rogan, but it did have the merit of being in an entirely different social sphere; the benefits to Consolidated Warfare Service would be real enough, so that Baines had not had to counterfeit a motive, which might have been detected by Ware and led to premature further questions; and finally, the objections Ware had raised, while in part unexpected, had been entirely consistent with everything the magician had said before, everything that he appeared to be, everything that his style proclaimed, despite the fact that he was obviously a complex man. Good. Baines liked consistent intellectuals, and wished that he had more of them in his organization. They were always fanatics of some sort when the chips were down, and hence presented him with some large and easily grasped handle precisely when he had most need of it. Ware hadn't exhibited his handle yet, but he would; he would. "It's worth it," Baines said, without more than a decorous two seconds of apparent hesitation. "I do want to remind you, though, Dr. Ware, that Dr. Hess here is one of my conditions. I want you to allow him to watch while you operate." "Oh, very gladly," Ware said; with another smile that, this time, Baines found disquieting; it seemed false, even unctuous, and Ware was too much in command of himself to have meant the falsity not to be noticed. "I'm sure he'll enjoy it. You can all watch, if you like. I may even invite Father Domenico." VIII Dr. Hess arrived punctually the next morning for his appointment to be shown Ware's workroom and equipment. Greeting him with a professional nod -- "Coals to Newcastle, bringing Mitford and me up here for a tertiary," Hess found himself quoting in silent inanity -- Ware led the way to a pair of heavy, brocaded hangings behind his desk, which parted to reveal a heavy brass-bound door of what was apparently cypress wood. Among its fittings was a huge knocker with a face a little like the mask of tragedy, except that the eyes had cat-like pupils in them. Hess had thought himself prepared to notice everything and be surprised by nothing, but he was taken aback when the expression on the knocker changed, slightly but inarguably, when Ware touched it. Apparently expecting his startlement, Ware said without looking at him, "There's nothing in here really worth stealing, but if anything were taken it would cost me a tremendous amount of trouble to replace it, no matter how worthless it would prove to the thief. Also, there's the problem of contamination -- just one ignorant touch could destroy the work of months. It's rather like a bacteriology laboratory in that respect. Hence the Guardian. "Obviously there can't be a standard supply house for your tools," Hess agreed, recovering his composure. "No, that's not even theoretically possible. The operator must make everything himself -- not as easy now as it was in the Middle Ages, when most educated men had the requisite skills as a matter of course. Here we go." The door swung back as if being opened from the inside, slowly and soundlessly. At first it yawned on a deep scarlet gloom, but Ware touched a switch, and, with a brief rushing sound, like water, sunlight flooded the room. Immediately Hess could see why Ware had rented this particular palazzo and no other. The room was an immense refectory of Sienese design, which in its heyday must often have banquetted as many as thirty nobles; there could not be another one half as big in Positano, though the palazzo as a whole was smaller than some. There were mullioned windows overhead, under the ceiling, running around all four walls, and the sunlight was pawing through two ranks of them. They were flanked by pairs of red-velvet drapes, unpatterned, hung from traverse rods; it had been these that Hess had heard pulling back when Ware had flipped the wall switch. At the rear of the room was another door, a broad one also covered by hangings, which Hess supposed must lead to a pantry or kitchen. To the left of this was a medium-sized, modern electric furnace, and beside it an anvil bearing a hammer that looked almost too heavy for Ware to lift. On the other side of the furnace from the anvil were several graduated tubs, which obviously served as quenching baths. To the right of the door was a black-topped chemist's bench, complete with sinks, running water and the usual nozzles for illuminating gas, vacuum and compressed air; Ware must have had to install his own pumps for all of these. Over the bench on the back wall were shelves of reagents; to the right, on the side wall, ranks of drying pegs, some of which bore contorted pieces of glassware, others, coils of rubber tubing. Farther along the wall toward the front was a lectern bearing a book as big as an unabridged dictionary, bound in red leather and closed and locked with a strap. There was a circular design chased in gold on the front of the book, but at this distance Hess could not make out what it was. The lectern was flanked by two standing candlesticks with fat candles in them; the candles had been extensively used, although there were shaded electric-light fixtures around the walls, too, and the small writing table next to the lectern bore a Tensor lamp. On the table was another book, smaller but almost as thick, which Hess recognized at once: the Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, forty-seventh edition, as standard a laboratory fixture as a test tube; and, a rank of quill pens and inkhorns. "Now you can see something of what I meant by requisite skills," Ware said. "Of course I blow much of my own glassware, but any ordinary chemist does that. But should I need a new sword, for instance" -- he pointed toward the electric furnace -- "I'd have to forge it myself. I couldn't just pick one up at a costume shop. I'd have to do a good job of it, too. As a modem writer says somewhere, the only really serviceable symbol for a sharp sword is a sharp sword." "Uhm," Hess said, continuing to look around. Against the left wall, opposite the lectern, was a long heavy table, bearing a neat ranking of objects ranging in length from six inches to about three feet, all closely wrapped in red silk. The wrappers had writing on them, but again Hess could not decipher it. Beside the table, affixed to the wall, was a flat sword cabinet. A few stools completed the furnishings; evidently Ware seldom worked sitting down. The floor was parqueted, and toward the center of the room still bore traces of marks in colored chalks, considerably scuffed, which brought from Ware a grunt of annoyance. "The wrapped instruments are all prepared and I'd rather not expose them," the magician said, walking toward the sword rack, "but of course I keep a set of spares and I can show you those." He opened the cabinet door, revealing a set of blades hung in order of size. There were thirteen of them. Some were obviously swords; others looked more like shoemaker's tools. "The order in which you make these is important, too," Ware said, "because, as you can see, most of them have writing on them, and it makes a difference what instrument does the writing. Hence I began with the uninscribed instrument, this one, the bolline or sickle, which is also one of the most often used. Rituals differ, but the one I use requires starting with a piece of unused steel. It's fired three times, and then quenched in a mixture of magpie's blood and the juice of an herb called foirole." "The Grimorium Verum says mole's blood and pimpernel juice," Hess observed. "Ah, good, you've been doing some reading. I've tried that, and it just doesn't seem to give quite as good an edge." "I should think you could get a still better edge by finding out what specific compounds were essential and using those," Hess said. "You'll remember that Damascus steel used to be tempered by plunging the sword into the body of a slave. It worked, but modem quenching baths are a lot better -- and in your case you wouldn't have to be constantly having to trap elusive animals in large numbers." "The analogy is incomplete," Ware said. "It would hold if tempering were the only end in view, or if the operation were only another observance of Paracelsus' rule, Alterius non sit qui suus esse potest -- doing for yourself what you can't trust others to do. Both are practical ends that I might satisfy in some quite different way. But in magic the blood sacrifice has an additional function -- what we might call the tempering of, not just the steel, but also the operator." "I see. And I suppose it has some symbolic functions, too." "In goetic art, everything does. In the same way, as you probably also know from your reading, the forging and quenching is to be done on a Wednesday in either the first or the eighth of the day hours, or the third or the tenth of the night hours, under a full Moon. There is again an immediate practical interest being served here -- for I assure you that the planetary hours do indeed affect affairs on Earth -- but also a psychological one, the obedience of the operator in every step. The grimoires and other handbooks are at best so confused and contradictory that it's never possible to know completely what steps are essential and what aren't, and research into the subject seldom makes for a long life." "All right," Hess said. "Go on." "Well, the horn handle has next to be shaped and fitted, again in a particular way at a particular hour, and then perfected at still another day and hour. By the way, you mentioned a different steeping bath. If you use that ritual, the days and the hours are also different, and again the question is, what's essential and what isn't? Thereafter, there's a conjuration to be recited, plus three salutations and a warding spell. Then the instrument is sprinkled, wrapped and fumigated -- not in the modern sense, I mean it's perfumed -- and is ready to use. After it's used, it has to be exorcised and re-dedicated, and that's the difference between the wrapped tools on the table and those hanging here in the rack. "I won't go into detail about the preparation of the other instruments. The next one I make is the pen of the Art followed by the inkpots and the inks, for obvious reasons -- and, for the same reasons, the burin or graver. The pens are on my desk. This fitted needle here is the burin. The rest, going down the line as they hang here rather than in order of manufacture, are the white-handled knife, which like the bolline is nearly an all-purpose tool ... the black-handled knife, used almost solely for inscribing the circle ... the stylet, chiefly for preparing the wooden knives used in tanning ... the wand or blasting rod, which describes itself ... the lancet, again self-descriptive ... the staff, a restraining instrument analogous to a shepherd's ... and lastly the four swords, one for the master, the other three for his assistants, if any." With a side-glance at Ware for permission, Hess leaned forward to inspect the writings on the graven instruments. Some of them were easy enough to make out: on the sword of the master, for instance, the word MICHAEL appeared on the pommel, and on the blade, running from point to hilt, ELOHIM GIBOR. On the other hand, on the handle of the white-handled knife was engraved the following: Hess pointed to this, and to a different but equally baffling inscription that was duplicated on the handles of the stylet and the lancet. "What do those mean?" "Mean? They can hardly be said to mean anything any more. They're greatly degenerate Hebrew characters, originally comprising various Divine Names. I could tell you what the Names were once, but the characters have no content any more -- they just have to be there." "Superstition," Hess aid, recalling his earlier conversation with Baines, interpreting Ware's remark about Christmas. "Precisely, in the pure sense. The process is as fundamental to the Art as evolution is to biology. Now if you'll step this way, I'll show you some other aspects that may interest you." He led the way diagonally across the room to the chemist's bench, pausing to rub irritatedly at the chalk marks with the sole of his slipper. "I suppose a modem translation of that aphorism of Paracelsus," he said, "would be 'You just can't get good servants any more.' Not to ply mops, anyhow.... Now, most of these reagents will be familiar to you, but some of them are special to the Art. This, for instance, is exorcised water, which as you see I need in great quantities. It has to be river water to start with. The quicklime is for tanning. Some laymen, de Camp for instance, will tell you that 'virgin parchment' simply means parchment that's never been written on before, but that's not so -- all the grimoires insist that it must be the skin of a male animal that has never engendered, and the Clavicula Salomonis sometimes insists upon unborn parchment, or the caul of a newborn child. For tanning I also have to grind my own salt, after the usual rites are said over it. The candles I use have to be made of the first wax taken from a new hive, and so do my almadels. If I need images, I have to make them of earth dug up with my bare hands and reduced to a paste without any tool. And so on. "I've mentioned aspersion and fumigation, in other words sprinkling and perfuming. Sprinkling has to be done with an aspergillum, a bundle of herbs like a fagot or bouquet garni. The herbs differ from rite to rite and you can see I've got a fair selection here -- mint, marjoram, rosemary, vervain, periwinkle, sage, valerian, ash, basil, hyssop. In fumigation the most commonly used scents are aloes, incense, mace, benzoin, storax. Also, it's sometimes necessary to make a stench -- for instance in the fumigation of a caul --- and I've got quite a repertoire of those." Ware turned away abruptly, nearly treading on Hess' toes and strode toward the exit. Hess had no choice but to follow him. "Everything involves special preparation," he said over his shoulder,"even including the firewood if I want to make ink for pacts. But there's no point in my cataloging things further, since I'm sure you thoroughly understand the principles." Hess scurried after, but he was still several paces behind the magician when the window drapes swished closed and the red gloom was reinstated. Ware stopped and waited for him, and the moment he was through the door, closed it and went back to his seat behind the big desk. Hess, puzzled, walked around the desk and took one of the Florentine chairs reserved for guests or clients. "Most illuminating," he said politely. "Thank you." "You're welcome." Ware rested his elbows on the desk and put his fingertips over his mouth, looking down thoughtfully. There was a sprinkle of perspiration over his brow and shaven head, and he seemed more than usually pale; also, Hess noticed after a moment, he seemed to be trying, without major effort, to control his breathing. Hess watched curiously, wondering what could have upset him. After only a moment, however, Ware looked up at him and volunteered the explanation, with an easy half smile. "Excuse me, he said. "From apprenticeship on, we're trained to secrecy. I'm perfectly convinced that it's unnecessary these days, and has been since the Inquisition died, but old oaths are the hardest to reason away. No discourtesy intended." "No offense taken," Hess assured him. "However, if you'd rather rest ..." "No, I'll have ample rest in the next three days, and be incommunicado, too, preparing for Dr. Baines' commission. So if you've further questions, now's the time for them." "Well ... I have no further technical questions, for the moment. But I am curious about a question Baines asked you during your first meeting -- I needn't pretend, I'm sure, that I haven't heard the tape. I wonder, just as he did, what your motivation is. I can see from what you've shown me, and from everything you've said, that you've taken colossal amounts of trouble to perfect yourself in your Art, and that you believe in it. So it doesn't matter for the present whether or not I believe in it, only whether or not I believe in you. And your laboratory isn't a sham, it isn't there solely for extortion's sake, it's a place where a dedicated man works at something he thinks important. I confess I came to scoff -- and to expose you, if I could -- and I still can't credit that any of what you do works, or ever did work. But I accept that you do believe." Ware gave him a half nod. "Thank you; go on." "I've no further to go but the fundamental question. You don't really need money, you don't seem to collect art or women, you're not out to be President of the World or the power behind some such person -- and yet by your lights you have damned yourself eternally to make yourself expert in this highly peculiar subject. What on earth for?" "l could easily duck that question," Ware said slowly. "I could point out, for instance, that under certain circumstances I could prolong my life to seven hundred years, and so might not be worrying just yet about what might happen to me in the next world. Or I could point out what you already know from the texts, that every magician hopes to cheat Hell in the end -- as several did who are now nicely ensconced on the calendar as authentic saints. "But the real fact of the matter, Dr. Hess, is that I think what I'm after is worth the risk, and what I'm after is something you understand perfectly, and for which you've sold your own soul, or if you prefer an only slightly less loaded word, your integrity, to Dr. Baines -- knowledge." "Uhmn. Surely there must be easier ways --" "You don't believe that. You think there may be more reliable ways, such as scientific method, but you don't think they're any easier. I myself have the utmost respect for scientific method, but I know that it doesn't offer me the kind of knowledge I'm looking for -- which is also knowledge about the makeup of the universe and how it is run, but not a kind that any exact science can provide me with, because the sciences don't accept that some of the forces of nature are Persons. Well, but some of them are. And without dealing with those Persons I shall never know any of the things I want to know. "This kind of research is just as expensive as underwriting a gigantic particle accelerator, Dr. Hess, and obviously I'll never get any government to underwrite it. But people like Dr. Baines can, if I can find enough of them -- just as they underwrite you. ''Eventually, I may have to pay for what I've learned with a jewel no amount of money could buy. Unlike Macbeth, I know one can't 'skip the life to come.' But even if it does come to that, Dr. Hess -- and probably it will -- I'll take my knowledge with me, and it will have been worth the price. "In other words -- just as you suspected -- I'm a fanatic." To his own dawning astonishment, Hess said slowly: "Yes. Yes, of course ... so am I." IX Father Domenico lay in his strange bed on his back, staring sleeplessly up at the pink stucco ceiling. Tonight was the night he had come for. Ware's three days of fasting, lustration and prayer -- surely a blasphemous burlesque of such observances as the Church knew them, in intent if not in content -- were over, and he had pronounced himself ready to act. Apparently he still intended to allow Baines and his two repulsive henchmen to observe the conjuration, but if he had ever had any intention of including Father Domenico in the Ceremony, he had thought better of it. That was frustrating, as well as a great relief; but, in his place, Father Domenico would have done the same thing. Yet even here, excluded from the scene and surrounded by every protection he had been able to muster, Father Domenico could feel the preliminary oppression, like the dead weather before an earthquake. There was always a similar hush and tension in the air just before the invocation of one of the Celestial Powers, but with none of these overtones of maleficence and disaster ... or would someone ignorant of what was actually proposed be able to tell the difference? That was a disquieting thought in itself, but one that could practically be left to Bishop Berkeley and the logical positivists. Father Domenico knew what was going on -- a ritual of supernatural murder; and could not help but tremble in his bed. Somewhere in the Palazzo there was the silvery sound of a small clock striking, distant and sweet. The time was now 10:00 P.M., the fourth hour of Saturn on the day of Saturn, the hour most suitable -- as even the blameless and pitiable Peter de Abano had written -- for experiments of hatred, enmity and discord; and Father Domenico, under the Covenant, was forbidden even to pray for failure. The clock, that two-handed engine that stands behind the Door, struck, and struck no more, and Ware drew the brocaded hangings aside. Up to now, Baines, despite himself, had felt a little foolish in the girdled white-linen garment Ware had insisted upon, but he cheered up upon seeing Jack Ginsberg and Dr. Hess in the same vestments. As for Ware, be was either comical or terrible, depending upon what view one took of the proceedings, in his white Levite surcoat with red-silk embroidery on the breast, his white-leather shoes lettered in cinnabar, and his paper crown bearing the word EL. He was girdled with a belt about three inches wide, which seemed to have been made from the skin of some hairy, lion-colored animal. Into the girdle was thrust a red-wrapped, scepter-like object, which Baines identified tentatively from a prior description of Hess' as the wand of power. "And now we must vest ourselves," Ware said, almost in a whisper. "Dr. Baines, on the desk you will find three garments. Take one, and then another, and another. Give two to Dr. Hess and Mr. Ginsberg. Don the other yourself." Baines picked up the huddle of cloth. It turned out to be an alb. "Take up your vestments and lift them in your hands above your heads. At the amen, let them fall. Now: "ANTON, AMATOR, EMITES, THEODONIEL, PONCOR, PAGOR, ANITOR, by the virtue of these most holy angelic names do I clothe myself, O Lord of Lords, in my Vestments of Power, that so that I may fulfill, even unto their term, all things which I desire to effect through Thee, IDEODANIACH, PAMOR, PLAIOR, Lord of Lords, whose kingdom and rule endureth forever and ever. Amen." The garments rustled down, and Ware opened the door. The room beyond was only vaguely lit with yellow candlelight, and at first bore almost no resemblance to the chamber Dr. Hess had described to Baines. As his eyes accommodated, however, Baines was gradually able to see that it was the same room, its margins now indistinct and its furniture slightly differently ordered: only the lectern and the candlesticks -- there were now four of them, not two -- were moved out from the walls and hence more or less visible. But it was still confusing, a welter of flickering shadows and slightly sickening perfume, most unlike the blueprint of the room that Baines had erected in his mind from Hess' drawing. The thing that dominated the real room itself was also a drawing, not any piece of furniture or detail of architecture: a vast double circle on the floor in what appeared to be whitewash. Between the concentric circles were written innumerable words, or what might have been words, in characters which might have been Hebrew, Greek, Etruscan or even Elvish for all Baines could tell. Some few were in Roman lettering, but they, too, were names he could not recognize; and around the outside of the outer circle were written astrological signs in their zodiacal order, but with Saturn to the north. At the very center of this figure was a ruled square about two feet on a side, from each corner of which proceeded chalked, conventionalized crosses, which did not look in the least Christian. Proceeding from each of these, but not connected to them, were four six-pointed stars, verging on the innermost circle. The stars at the east, west and south each had a Tau scrawled at their centers; presumably the Saturnmost did too, but if so it could not be seen, for the heart of that emplacement was hidden by what seemed to be a fat puddle of stippled fur. Outside the circles, at the other compass points, were drawn four pentagrams, in the chords of which were written TE TRA GRAM MA TON, and at the centers of which stood the candles. Farthest away from all this -- about two feet outside the circle and three feet over it to the north -- was a circle enclosed by a triangle, also much lettered inside and out; Baines could just see that the characters in the angles of the triangle read NI CH EL. "Tanists," Ware whispered, pointing into the circle, "take your places." He went toward the long table Hess had described and vanished in the gloom. As instructed, Baines walked into the circle and stood in the western star; Hess followed, taking the eastern; and Ginsberg, very slowly, crept into the southern. To the north, the puddle of fur revolved once widdershins and resettled itself with an unsettling sigh, 'making Jack Ginsberg jump. Baines inspected it belatedly. Probably it was only a cat, as was supposed to be traditional, but in this light it looked more like a badger. Whatever it was, it was obscenely fat. Ware reappeared, carrying a sword. He entered the circle, closed it with the point of the sword, and proceeded to the central square, where he lay the sword across the toes of his white shoes; then he drew the wand from his belt and unwrapped it, laying the red-silk cloth across his shoulders. "From now on," he said, in a normal, even voice, "no one is to move." From somewhere inside his vestments he produced a small crucible, which he set at his feet before the recumbent sword. Small blue flames promptly began to rise from the bowl, and Ware cast incense into it. He said: "Holocaust. Holocaust. Holocaust." The flames in the brazier rose slightly. "We are to call upon MARCHOSIAS, a great marquis of the Descending Hierarchy," Ware said in the same conversational voice. "Before he fell, he belonged to the Order of Dominations among the angels, and thinks to return to the Seven Thrones after twelve hundred years. His virtue is that he gives true answers. Stand fast, all." With a sudden motion, Ware thrust the end of his rod into the surging flames of the brazier. At once the air of the hall rang with a long, frightful chain of woeful howls. Above the bestial clamor, Ware shouted: "I adjure thee, great MARCHOSIAS, as the agent of the Emperor LUCIFER, and of his beloved son LUCIFUGE ROFOCALE, by the power of the pact I have with thee, and by the Names ADONAY, ELOIM, JEHOVAM, TAGLA, MATHON, ALMOUZIN, ARIOS, PITHONA, MAGOTS, SYLPHAE, TABOTS, SALAMANDRAE, GNOMUS, TERRAE, COELIS, GODENS, AQUA, and by the whole hierarchy of superior intelligences who shall constrain thee against thy will, venite, venite, submiritillor MARCHOSIAS!" The noise rose higher, and a green steam began to come off the brazier. It smelt like someone was burning hart's horn and fish gall. But there was no other answer. His face white and cruel, Ware rasped over the tumult: "I adjure thee, MARCHOSIAS, by the pact, and by the Names, appear instanter!" He plunged the rod a second time into the flames. The room screamed; but still there was no apparition. "Now I adjure thee, LUCIFUGE ROFOCALE, whom I command, as the agent of the Lord and Emperor of Lords, send me thy messenger MARCHOSIAS, forcing him to forsake his hiding place, wheresoever it may be, and warning thee --" The rod went back into the fire. Instantly, the palazzo rocked as though the earth had moved under it. "Stand fast!" Ware said hoarsely. Something Else said: HUSH, I AM HERE. WHAT DOST THOU SEEK OF ME? WHY DOST THOU DISTURB MY REPOSE? LET MY FATHER REST, AND HOLD THY ROD. Never had Baines heard a voice like that before. It seemed to speak in syllables of burning ashes. "Hadst thou appeared when first I invoked thee, I had by no means smitten thee, nor called thy father," Ware said. "Remember, if the request I make of thee be refused, I shall thrust again my rod into the fire." THINK AND SEE! The palazzo

shuddered again. Then, from the middle of the triangle to the northwest, a

slow cloud of yellow fumes went up toward the ceiling,

making them all cough, even Ware. As it spread and thinned, Baines could see a shape