|

THE IRAQ STUDY GROUP REPORT |

||||

RECOMMENDATION 40: The United States should not make an open-ended commitment to keep large numbers of American troops deployed in Iraq. RECOMMENDATION 41: The United States must make it clear to the Iraqi government that the United States could carry out its plans, including planned redeployments, even if Iraq does not implement its planned changes. America’s other security needs and the future of our military cannot be made hostage to the actions or inactions of the Iraqi government. RECOMMENDATION 42: We should seek to complete the training and equipping mission by the first quarter of 2008, as stated by General George Casey on October 24, 2006. RECOMMENDATION 43: Military priorities in Iraq must change, with the highest priority given to the training, equipping, advising, and support mission and to counterterrorism operations. RECOMMENDATION 44: The most highly qualified U.S. officers and military personnel should be assigned to the imbedded teams, and American teams should be present with Iraqi units down to the company level. The U.S. military should establish suitable career-enhancingi ncentives for these officers and personnel. RECOMMENDATION 45: The United States should support more and better equipment for the Iraqi Army by encouraging the Iraqi government to accelerate its Foreign Military Sales requests and, as American combat brigades move out of Iraq, by leaving behind some American equipment for Iraqi forces. We recognize that there are other results of the war in Iraq that have great consequence for our nation. One consequence has been the stress and uncertainty imposed on our military—the most professional and proficient military in history. The United States will need its military to protect U.S. security regardless of what happens in Iraq. We therefore considered how to limit the adverse consequences of the strain imposed on our military by the Iraq war. U.S. military forces, especially our ground forces, have been stretched nearly to the breaking point by the repeated deployments in Iraq, with attendant casualties (almost 3,000 dead and more than 21,000 wounded), greater difficulty in recruiting, and accelerated wear on equipment. Additionally, the defense budget as a whole is in danger of disarray, as supplemental funding winds down and reset costs become clear. It will be a major challenge to meet ongoing requirements for other current and future security threats that need to be accommodated together with spending for operations and maintenance, reset, personnel, and benefits for active duty and retired personnel. Restoring the capability of our military forces should be a high priority for the United States at this time. The U.S. military has a long tradition of strong partnership between the civilian leadership of the Department of Defense and the uniformed services. Both have long benefited from a relationship in which the civilian leadership exercises control with the advantage of fully candid professional advice, and the military serves loyally with the understanding that its advice has been heard and valued. That tradition has frayed, and civil-military relations need to be repaired. RECOMMENDATION 46: The new Secretary of Defense should make every effort to build healthy civil-military relations, by creating an environment in which the senior military feel free to offer independent advice not only to the civilian leadership in the Pentagon but also to the President and the National Security Council, as envisioned in the Goldwater-Nichols legislation. RECOMMENDATION 47: As redeployment proceeds, the Pentagon leadership should emphasize training and education programs for the forces that have returned to the continental United States in order to “reset” the force and restore the U.S. military to a high level of readiness for global contingencies. RECOMMENDATION 48: As equipment returns to the United States, Congress should appropriate sufficient funds to restore the equipment to full functionality over the next five years. RECOMMENDATION 49: The administration, in full consultation with the relevant committees of Congress, should assess the full future budgetary impact of the war in Iraq and its potential impact on the future readiness of the force, the ability to recruit and retain high-quality personnel, needed investments in procurement and in research and development, and the budgets of other U.S. government agencies involved in the stability and reconstruction effort. 4. Police and Criminal Justice The problems in the Iraqi police and criminal justice system are profound. The ethos and training of Iraqi police forces must support the mission to “protect and serve” all Iraqis. Today, far too many Iraqi police do not embrace that mission, in part because of problems in how reforms were organized and implemented by the Iraqi and U.S. governments. Within Iraq, the failure of the police to restore order and prevent militia infiltration is due, in part, to the poor organization of Iraq’s component police forces: the Iraqi National Police, the Iraqi Border Police, and the Iraqi Police Service. The Iraqi National Police pursue a mission that is more military than domestic in nature—involving commando-style operations—and is thus ill-suited to the Ministry of the Interior. The more natural home for the National Police is within the Ministry of Defense, which should be the authority for counterinsurgency operations and heavily armed forces. Though depriving the Ministry of the Interior of operational forces, this move will place the Iraqi National Police under better and more rigorous Iraqi and U.S. supervision and will enable these units to better perform their counterinsurgency mission. RECOMMENDATION 50: The entire Iraqi National Police should be transferred to the Ministry of Defense, where the police commando units will become part of the new Iraqi Army. Similarly, the Iraqi Border Police are charged with a role that bears little resemblance to ordinary policing, especially in light of the current flow of foreign fighters, insurgents, and weaponry across Iraq’s borders and the need for joint patrols of the border with foreign militaries. Thus the natural home for the Border Police is within the Ministry of Defense, which should be the authority for controlling Iraq’s borders. RECOMMENDATION 51: The entire Iraqi Border Police should be transferred to the Ministry of Defense, which would have total responsibility for border control and external security. The Iraqi Police Service, which operates in the provinces and provides local policing, needs to become a true police force. It needs legal authority, training, and equipment to control crime and protect Iraqi citizens. Accomplishing those goals will not be easy, and the presence of American advisors will be required to help the Iraqis determine a new role for the police. RECOMMENDATION 52: The Iraqi Police Service should be given greater responsibility to conduct criminal investigations and should expand its cooperation with other elements in the Iraqi judicial system in order to better control crime and protect Iraqi civilians. In order to more effectively administer the Iraqi Police Service, the Ministry of the Interior needs to undertake substantial reforms to purge bad elements and highlight best practices. Once the ministry begins to function effectively, it can exert a positive influence over the provinces and take back some of the authority that was lost to local governments through decentralization. To reduce corruption and militia infiltration, the Ministry of the Interior should take authority from the local governments for the handling of policing funds. Doing so will improve accountability and organizational discipline, limit the authority of provincial police officials, and identify police officers with the central government. RECOMMENDATION 53: The Iraqi Ministry of the Interior should undergo a process of organizational transformation, including efforts to expand the capability and reach of the current major crime unit (or Criminal Investigation Division) and to exert more authority over local police forces. The sole authority to pay police salaries and disburse financial support to local police should be transferred to the Ministry of the Interior. Finally, there is no alternative to bringing the Facilities Protection Service under the control of the Iraqi Ministry of the Interior. Simply disbanding these units is not an option, as the members will take their weapons and become full-time militiamen or insurgents. All should be brought under the authority of a reformed Ministry of the Interior. They will need to be vetted, retrained, and closely supervised. Those who are no longer part of the Facilities Protection Service need to participate in a disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration program (outlined above). RECOMMENDATION 54: The Iraqi Ministry of the Interior should proceed with current efforts to identify, register, and control the Facilities Protection Service. U.S. Actions The Iraqi criminal justice system is weak, and the U.S. training mission has been hindered by a lack of clarity and capacity. It has not always been clear who is in charge of the police training mission, and the U.S. military lacks expertise in certain areas pertaining to police and the rule of law. The United States has been more successful in training the Iraqi Army than it has the police. The U.S. Department of Justice has the expertise and capacity to carry out the police training mission. The U.S. Department of Defense is already bearing too much of the burden in Iraq. Meanwhile, the pool of expertise in the United States on policing and the rule of law has been underutilized. The United States should adjust its training mission in Iraq to match the recommended changes in the Iraqi government—the movement of the National and Border Police to the Ministry of Defense and the new emphasis on the Iraqi Police Service within the Ministry of the Interior. To reflect the reorganization, the Department of Defense would continue to train the Iraqi National and Border Police, and the Department of Justice would become responsible for training the Iraqi Police Service. RECOMMENDATION 55: The U.S. Department of Defense should continue its mission to train the Iraqi National Police and the Iraqi Border Police, which should be placed within the Iraqi Ministry of Defense. RECOMMENDATION 56: The U.S. Department of Justice should direct the training mission of the police forces remaining under the Ministry of the Interior. RECOMMENDATION 57: Just as U.S. military training teams are imbedded within Iraqi Army units, the current practice of imbedding U.S. police trainers should be expanded and then umbers of civilian training officers increased so that teams can cover all levels of the Iraqi Police Service, including local police stations. These trainers should be obtained from among experienced civilian police executives and supervisors from around the world. These officers would replace the military police personnel currently assigned to training teams. The Federal Bureau of Investigation has provided personnel to train the Criminal Investigation Division in the Ministry of the Interior, which handles major crimes. The FBI has also fielded a large team within Iraq for counterterrorism activities. Building on this experience, the training programs should be expanded and should include the development of forensic investigation training and facilities that could apply scientific and technical investigative methods to counterterrorism as well as to ordinary criminal activity. RECOMMENDATION 58: The FBI should expand its investigative and forensic training and facilities within Iraq, to include coverage of terrorism as well as criminal activity. One of the major deficiencies of the Iraqi Police Service is its lack of equipment, particularly in the area of communications and motor transport. RECOMMENDATION 59: The Iraqi government should provide funds to expand and upgrade communications equipment and motor vehicles for the Iraqi Police Service. The Department of Justice is also better suited than the Department of Defense to carry out the mission of reforming Iraq’s Ministry of the Interior and Iraq’s judicial system. Iraq needs more than training for cops on the beat: it needs courts, trained prosecutors and investigators, and the ability to protect Iraqi judicial officials. RECOMMENDATION 60: The U.S. Department of Justice should lead the work of organizational transformation in the Ministry of the Interior. This approach must involve Iraqi officials, starting at senior levels and moving down, to create a strategic plan and work out standard administrative procedures, codes of conduct, and operational measures that Iraqis will accept and use. These plans must be drawn up in partnership. RECOMMENDATION 61: Programs led by the U.S. Department of Justice to establish courts; to train judges, prosecutors, and investigators; and to create institutions and practices to fight corruption must be strongly supported and funded. New and refurbished courthouses with improved physical security, secure housing for judges and judicial staff, witness protection facilities, and a new Iraqi Marshals Service are essential parts of a secure and functioning system of justice. Since the success of the oil sector is critical to the success of the Iraqi economy, the United States must do what it can to help Iraq maximize its capability. Iraq, a country with promising oil potential, could restore oil production from existing fields to 3.0 to 3.5 million barrels a day over a three to five-year period, depending on evolving conditions in key reservoirs. Even if Iraq were at peace tomorrow, oil production would decline unless current problems in the oil sector were addressed. Short Term RECOMMENDATION 62: • As soon as possible, the U.S. government should provide technical assistance to the Iraqi government to prepare a draft oil law that defines the rights of regional and local governments and creates a fiscal and legal framework for investment. Legal clarity is essential to attract investment. • The U.S. government should encourage the Iraqi government to accelerate contracting for the comprehensive well work-overs in the southern fields needed to increase production, but the United States should no longer fund such infrastructure projects. • The U.S. military should work with the Iraqi military and with private security forces to protect oil infrastructure and contractors. Protective measures could include a program to improve pipeline security by paying local tribes solely on the basis of throughput (rather than fixed amounts). • Metering should be implemented at both ends of the supply line. This step would immediately improve accountability in the oil sector. • In conjunction with the International Monetary Fund, the U.S. government should press Iraq to continue reducing subsidies in the energy sector, instead of providing grant assistance. Until Iraqis pay market prices for oil products, drastic fuel shortages will remain. Long Term Expanding oil production in Iraq over the long term will require creating corporate structures, establishing management systems, and installing competent managers to plan and oversee an ambitious list of major oil-field investment projects. To improve oil-sector performance, the Study Group puts forward the following recommendations. RECOMMENDATION 63: • The United States should encourage investment in Iraq’s oil sector by the international community and by international energy companies. • The United States should assist Iraqi leaders to reorganize the national oil industry as a commercial enterprise, in order to enhance efficiency, transparency, and accountability. • To combat corruption, the U.S. government should urge the Iraqi government to post all oil contracts, volumes, and prices on the Web so that Iraqis and outside observers can track exports and export revenues. • The United States should support the World Bank’s efforts to ensure that best practices are used in contracting. This support involves providing Iraqi officials with contracting templates and training them in contracting, auditing, and reviewing audits. • The United States should provide technical assistance to the Ministry of Oil for enhancing maintenance, improving the payments process, managing cash flows, contracting and auditing, and updating professional training programs for management and technical personnel. 6. U.S. Economic and Reconstruction Assistance Building the capacity of the Iraqi government should be at the heart of U.S. reconstruction efforts, and capacity building demands additional U.S. resources. Progress in providing essential government services is necessary to sustain any progress on the political or security front. The period of large U.S.-funded reconstruction projects is over, yet the Iraqi government is still in great need of technical assistance and advice to build the capacity of its institutions. The Iraqi government needs help with all aspects of its operations, including improved procedures, greater delegation of authority, and better internal controls. The strong emphasis on building capable central ministries must be accompanied by efforts to develop functioning, effective provincial government institutions with local citizen participation. Job creation is also essential. There is no substitute for private-sector job generation, but the Commander’s Emergency Response Program is a necessary transitional mechanism until security and the economic climate improve. It provides immediate economic assistance for trash pickup, water, sewers, and electricity in conjunction with clear, hold, and build operations, and it should be funded generously. A total of $753 million was appropriated for this program in FY2006. RECOMMENDATION 64: U.S. economic assistance should be increased to a level of $5 billion per year rather than being permitted to decline. The President needs to ask for the necessary resources and must work hard to win the support of Congress. Capacity building and job creation, including reliance on the Commander’s Emergency Response Program, should be U.S. priorities. Economic assistance should be provided on a nonsectarian basis. The New Diplomatic Offensive can help draw in more international partners to assist with the reconstruction mission. The United Nations, the World Bank, the European Union, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and some Arab League members need to become hands-on participants in Iraq’s reconstruction. RECOMMENDATION 65: An essential part of reconstruction efforts in Iraq should be greater involvement by and with international partners, who should do more than just contribute money. They should also actively participate in the design and construction of projects. The number of refugees and internally displaced persons within Iraq is increasing dramatically. If this situation is not addressed, Iraq and the region could be further destabilized, and the humanitarian suffering could be severe. Funding for international relief efforts is insufficient, and should be increased. RECOMMENDATION 66: The United States should take the lead in funding assistance requests from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and other humanitarian agencies. Coordination of Economic and Reconstruction Assistance A lack of coordination by senior management in Washington still hampers U.S. contributions to Iraq’s reconstruction. Focus, priority setting, and skillful implementation are in short supply. No single official is assigned responsibility or held accountable for the overall reconstruction effort. Representatives of key foreign partners involved in reconstruction have also spoken to us directly and specifically about the need for a point of contact that can coordinate their efforts with the U.S. government. A failure to improve coordination will result in agencies continuing to follow conflicting strategies, wasting taxpayer dollars on duplicative and uncoordinated efforts. This waste will further undermine public confidence in U.S. policy in Iraq. A Senior Advisor for Economic Reconstruction in Iraq is required. He or she should report to the President, be given a staff and funding, and chair a National Security Council interagency group consisting of senior principals at the undersecretary level from all relevant U.S. government departments and agencies. The Senior Advisor’s responsibility must be to bring unity of effort to the policy, budget, and implementation of economic reconstruction programs in Iraq. The Senior Advisor must act as the principal point of contact with U.S. partners in the overall reconstruction effort. He or she must have close and constant interaction with senior U.S. officials and military commanders in Iraq, especially the Director of the Iraq Reconstruction and Management Office, so that the realities on the ground are brought directly and fully into the policy-making process. In order to maximize the effectiveness of assistance, all involved must be on the same page at all times. RECOMMENDATION 67: The President should create a Senior Advisor for Economic Reconstruction in Iraq. Improving the Effectiveness of Assistance Programs Congress should work with the administration to improve its ability to implement assistance programs in Iraq quickly, flexibly, and effectively. As opportunities arise, the Chief of Mission in Iraq should have the authority to fund quick-disbursing projects to promote national reconciliation, as well as to rescind funding from programs and projects in which the government of Iraq is not demonstrating effective partnership. These are important tools to improve performance and accountability—as is the work of the Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction. RECOMMENDATION 68: The Chief of Mission in Iraq should have the authority to spend significant funds through a program structured along the lines of the Commander’s Emergency Response Program, and should have the authority to rescind funding from programs and projects in which the government of Iraq is not demonstrating effective partnership. RECOMMENDATION 69: The authority of the Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction should be renewed for the duration of assistance programs in Iraq. U.S. security assistance programs in Iraq are slowed considerably by the differing requirements of State and Defense Department programs and of their respective congressional oversight committees. Since Iraqi forces must be trained and equipped, streamlining the provision of training and equipment to Iraq is critical. Security assistance should be delivered promptly, within weeks of a decision to provide it. RECOMMENDATION 70: A more flexible security assistance program for Iraq, breaking down the barriers to effective interagency cooperation, should be authorized and implemented. The United States also needs to break down barriers that discourage U.S. partnerships with international donors and Iraqi participants to promote reconstruction. The ability of the United States to form such partnerships will encourage greater international participation in Iraq. RECOMMENDATION 71: Authority to merge U.S. funds with those from international donors and Iraqi participants on behalf of assistance projects should be provided. 7. Budget Preparation, Presentation, and Review The public interest is not well served by the government’s preparation, presentation, and review of the budget for the war in Iraq. First, most of the costs of the war show up not in the normal budget request but in requests for emergency supplemental appropriations. This means that funding requests are drawn up outside the normal budget process, are not offset by budgetary reductions elsewhere, and move quickly to the White House with minimal scrutiny. By passing the normal review erodes budget discipline and accountability. Second, the executive branch presents budget requests in a confusing manner, making it difficult for both the general public and members of Congress to understand the request or to differentiate it from counterterrorism operations around the world or operations in Afghanistan. Detailed analyses by budget experts are needed to answer what should be a simple question: “How much money is the President requesting for the war in Iraq?” Finally, circumvention of the budget process by the executive branch erodes oversight and review by Congress. The authorizing committees (including the House and Senate Armed Services committees) spend the better part of a year reviewing the President’s annual budget request. When the President submits an emergency supplemental request, the authorizing committees are bypassed. The request goes directly to the appropriations committees, and they are pressured by the need to act quickly so that troops in the field do not run out of funds. The result is a spending bill that passes Congress with perfunctory review. Even worse, the must-pass appropriations bill becomes loaded with special spending projects that would not survive the normal review process. RECOMMENDATION 72: Costs for the war in Iraq should be included in the President’s annual budget request, starting in FY 2008: the war is in its fourth year, and the normal budget process should not be circumvented. Funding requests for the war in Iraq should be presented clearly to Congress and the American people. Congress must carry out its constitutional responsibility to review budget requests for the war in Iraq carefully and to conduct oversight.

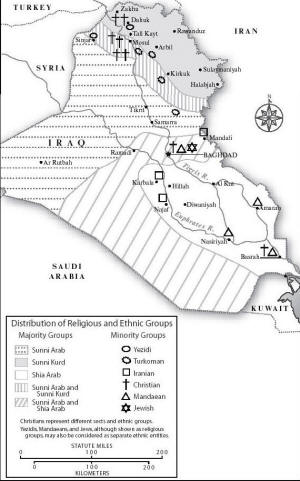

The United States can take several steps to ensure that it has personnel with the right skills serving in Iraq. All of our efforts in Iraq, military and civilian, are handicapped by Americans’ lack of language and cultural understanding. Our embassy of 1,000 has 33 Arabic speakers, just six of whom are at the level of fluency. In a conflict that demands effective and efficient communication with Iraqis, we are often at a disadvantage. There are still far too few Arab language– proficient military and civilian officers in Iraq, to the detriment of the U.S. mission. Civilian agencies also have little experience with complex overseas interventions to restore and maintain order—stability operations—outside of the normal embassy setting. The nature of the mission in Iraq is unfamiliar and dangerous, and the United States has had great difficulty filling civilian assignments in Iraq with sufficient numbers of properly trained personnel at the appropriate rank. RECOMMENDATION 73: The Secretary of State, the Secretary of Defense, and the Director of National Intelligence should accord the highest possible priority to professional language proficiency and cultural training, in general and specifically for U.S. officers and personnel about to be assigned to Iraq. RECOMMENDATION 74: In the short term, if not enough civilians volunteer to fill key positions in Iraq, civilian agencies must fill those positions with directed assignments. Steps should be taken to mitigate familial or financial hardships posed by directed assignments, including tax exclusions similar to those authorized for U.S. military personnel serving in Iraq. RECOMMENDATION 75: For the longer term, the United States government needs to improve how its constituent agencies—Defense, State, Agency for International Development, Treasury, Justice, the intelligence community, and others—respond to a complex stability operation like that represented by this decade’s Iraq and Afghanistan wars and the previous decade’s operations in the Balkans. They need to train for, and conduct, joint operations across agency boundaries, following the Goldwater-Nichols model that has proved so successful in the U.S. armed services. RECOMMENDATION 76: The State Department should train personnel to carry out civilian tasks associated with a complex stability operation outside of the traditional embassy setting. It should establish a Foreign Service Reserve Corps with personnel and expertise to provide surge capacity for such an operation. Other key civilian agencies, including Treasury, Justice, and Agriculture, need to create similar technical assistance capabilities. While the United States has been able to acquire good and sometimes superb tactical intelligence on al Qaeda in Iraq, our government still does not understand very well either the insurgency in Iraq or the role of the militias. A senior commander told us that human intelligence in Iraq has improved from 10 percent to 30 percent. Clearly, U.S. intelligence agencies can and must do better. As mentioned above, an essential part of better intelligence must be improved language and cultural skills. As an intelligence analyst told us, “We rely too much on others to bring information to us, and too often don’t understand what is reported back because we do not understand the context of what we are told.” The Defense Department and the intelligence community have not invested sufficient people and resources to understand the political and military threat to American men and women in the armed forces. Congress has appropriated almost $2 billion this year for countermeasures to protect our troops in Iraq against improvised explosive devices, but the administration has not put forward a request to invest comparable resources in trying to understand the people who fabricate, plant, and explode those devices. We were told that there are fewer than 10 analysts on the job at the Defense Intelligence Agency who have more than two years’ experience in analyzing the insurgency. Capable analysts are rotated to new assignments, and on-the-job training begins anew. Agencies must have a better personnel system to keep analytic expertise focused on the insurgency. They are not doing enough to map the insurgency, dissect it, and understand it on a national and provincial level. The analytic community’s knowledge of the organization, leadership, financing, and operations of militias, as well as their relationship to government security forces, also falls far short of what policy makers need to know. In addition, there is significant underreporting of the violence in Iraq. The standard for recording attacks acts as a filter to keep events out of reports and databases. A murder of an Iraqi is not necessarily counted as an attack. If we cannot determine the source of a sectarian attack, that assault does not make it into the database. A roadside bomb or a rocket or mortar attack that doesn’t hurt U.S. personnel doesn’t count. For example, on one day in July 2006 there were 93 attacks or significant acts of violence reported. Yet a careful review of the reports for that single day brought to light 1,100 acts of violence. Good policy is difficult to make when information is systematically collected in a way that minimizes its discrepancy with policy goals. RECOMMENDATION 77: The Director of National Intelligence and the Secretary of Defense should devote significantly greater analytic resources to the task of understanding the threats and sources of violence in Iraq. RECOMMENDATION 78: The Director of National Intelligence and the Secretary of Defense should also institute immediate changes in the collection of data about violence and the sources of violence in Iraq to provide a more accurate picture of events on the ground. Recommended Iraqi Actions The Iraqi government must improve its intelligence capability, initially to work with the United States, and ultimately to take full responsibility for this intelligence function. To facilitate enhanced Iraqi intelligence capabilities, the CIA should increase its personnel in Iraq to train Iraqi intelligence personnel. The CIA should also develop, with Iraqi officials, a counterterrorism intelligence center for the all-source fusion of information on the various sources of terrorism within Iraq. This center would analyze data concerning the individuals, organizations, networks, and support groups involved in terrorism within Iraq. It would also facilitate intelligence-led police and military actions against them. RECOMMENDATION 79: The CIA should provide additional personnel in Iraq to develop and train an effective intelligence service and to build a counterterrorism intelligence center that will facilitate intelligence-led counterterrorism efforts. Distribution of Religious and Ethnic Groups Letter from the Sponsoring Organizations The initiative for a bipartisan, independent, forward-looking “fresh-eyes” assessment of Iraq emerged from conversations U.S. House Appropriations Committee Member Frank Wolf had with us. In late 2005, Congressman Wolf asked the United States Institute of Peace, a bipartisan federal entity, to facilitate the assessment, in collaboration with the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy at Rice University, the Center for the Study of the Presidency, and the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Interested members of Congress, in consultation with the sponsoring organizations and the administration, agreed that former Republican U.S. Secretary of State James A. Baker, III and former Democratic Congressman Lee H. Hamilton had the breadth of knowledge of foreign affairs required to co-chair this bipartisan effort. The co-chairs subsequently selected the other members of the bipartisan Iraq Study Group, all senior individuals with distinguished records of public service. Democrats included former Secretary of Defense William J. Perry, former Governor and U.S. Senator Charles S. Robb, former Congressman and White House chief of staff Leon E. Panetta, and Vernon E. Jordan, Jr., advisor to President Bill Clinton. Republicans included former Associate Justice to the U.S. Supreme Court Sandra Day O’Connor, former U.S. Senator Alan K. Simpson, former Attorney General Edwin Meese III, and former Secretary of State Lawrence S. Eagleburger. Former CIA Director Robert Gates was an active member for a period of months until his nomination as Secretary of Defense. The Iraq Study Group was launched on March 15, 2006, in a Capitol Hill meeting hosted by U.S. Senator John Warner and attended by congressional leaders from both sides of the aisle. To support the Study Group, the sponsoring organizations created four expert working groups consisting of 44 leading foreign policy analysts and specialists on Iraq. The working groups, led by staff of the United States Institute of Peace, focused on the Strategic Environment, Military and Security Issues, Political Development, and the Economy and Reconstruction. Every effort was made to ensure the participation of experts across a wide span of the political spectrum. Additionally, a panel of retired military officers was consulted. We are grateful to all those who have assisted the Study Group, especially the supporting experts and staff. Our thanks go to Daniel P. Serwer of the Institute of Peace, who served as executive director; Christopher Kojm, advisor to the Study Group; John Williams, Policy Assistant to Mr. Baker; and Ben Rhodes, Special Assistant to Mr. Hamilton. Richard H. Solomon, President Edward P. Djerejian, Founding

Director David M. Abshire, President John J. Hamre, President Iraq Study Group Plenary Sessions March 15, 2006

Iraq Study Group Consultations Iraqi Officials and Representatives *Jalal Talabani—President Current U.S. Administration Officials

Senior Administration

Officials Department of Defense/Military CIVILIAN: MILITARY: Department of State/Civilian Embassy Personnel R. Nicholas Burns—Under Secretary of

State for Political Affairs John D. Negroponte—Director of

National Intelligence David Walker—Comptroller General of

the United States Senator William Frist

(R-TN)—Majority Leader Senator Jeff Bingaman (D-NM)—Ranking

Member, Energy and Resources Committee United States House of Representatives Representative Nancy Pelosi

(D-CA)—Minority Leader Sheikh Salem al-Abdullah al-Sabah—Ambassador

of Kuwait to the United States William J. Clinton—former President

of the United States Expert Working Groups and Military Senior Advisor Panel Gary Matthews, USIP Secretariat Raad Alkadiri Frederick D. Barton Jay Collins Jock P. Covey Keith Crane Amy Myers Jaffe K. Riva Levinson David A. Lipton Michael E. O’Hanlon James A. Placke James A. Schear Paul Hughes, USIP Secretariat Hans A. Binnendijk James Carafano Michael Eisenstadt Bruce Hoffman Clifford May Robert M. Perito Kalev I. Sepp John F. Sigler W. Andrew Terrill Jeffrey A. White Daniel P. Serwer, USIP Secretariat Larry Diamond Andrew P. N. Erdmann Reuel Marc Gerecht David L. Mack Phebe A. Marr Hassan Mneimneh Augustus Richard Norton Marina S. Ottaway Judy Van Rest Judith S. Yaphe Paul Stares, USIP Secretariat Jon B. Alterman Steven A. Cook Hillel Fradkin Chas W. Freeman Geoffrey Kemp Daniel C. Kurtzer Ellen Laipson William B. Quandt Shibley Telhami Wayne White Admiral James O. Ellis, Jr. General John M. Keane General Edward C. Meyer General Joseph W. Ralston Lieutenant General Roger C. Schultz,

Sr.

James A. Baker, III, has served in senior government positions under three United States presidents. He served as the nation’s 61st Secretary of State from January 1989 through August 1992 under President George H. W. Bush. During his tenure at the State Department, Mr. Baker traveled to 90 foreign countries as the United States confronted the unprecedented challenges and opportunities of the post–Cold War era. Mr. Baker’s reflections on those years of revolution, war, and peace—The Politics of Diplomacy—was published in 1995. Mr. Baker served as the 67th Secretary of the Treasury from 1985 to 1988 under President Ronald Reagan. As Treasury Secretary, he was also Chairman of the President’s Economic Policy Council. From 1981 to 1985, he served as White House Chief of Staff to President Reagan. Mr. Baker’s record of public service began in 1975 as Under Secretary of Commerce to President Gerald Ford. It concluded with his service as White House Chief of Staff and Senior Counselor to President Bush from August 1992 to January 1993. Long active in American presidential politics, Mr. Baker led presidential campaigns for Presidents Ford, Reagan, and Bush over the course of five consecutive presidential elections from 1976 to 1992. A native Houstonian, Mr. Baker graduated from Princeton University in 1952. After two years of active duty as a lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps, he entered the University of Texas School of Law at Austin. He received his J.D. with honors in 1957 and practiced law with the Houston firm of Andrews and Kurth from 1957 to 1975. Mr. Baker’s memoir—Work Hard, Study . . . and Keep Out of Politics! Adventures and Lessons from an Unexpected Public Life—was published in October 2006. Mr. Baker received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1991 and has been the recipient of many other awards for distinguished public service, including Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson Award, the American Institute for Public Service’s Jefferson Award, Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government Award, the Hans J. Morgenthau Award, the George F. Kennan Award, the Department of the Treasury’s Alexander Hamilton Award, the Department of State’s Distinguished Service Award, and numerous honorary academic degrees. Mr. Baker is presently a senior partner in the law firm of Baker Botts. He is Honorary Chairman of the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy at Rice University and serves on the board of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. From 1997 to 2004, Mr. Baker served as the Personal Envoy of United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan to seek a political solution to the conflict over Western Sahara. In 2003, Mr. Baker was appointed Special Presidential Envoy for President George W. Bush on the issue of Iraqi debt. In 2005, he was co-chair, with former President Jimmy Carter, of the Commission on Federal Election Reform. Since March 2006, Mr. Baker and former U.S. Congressman Lee H. Hamilton have served as the co-chairs of the Iraq Study Group, a bipartisan blue-ribbon panel on Iraq. Mr. Baker was born in Houston, Texas, in 1930. He and his wife, the former Susan Garrett, currently reside in Houston, and have eight children and seventeen grandchildren.

Lee H. Hamilton became Director of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in January 1999. Previously, Mr. Hamilton served for thirty-four years as a United States Congressman from Indiana. During his tenure, he served as Chairman and Ranking Member of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs (now the Committee on International Relations) and chaired the Subcommittee on Europe and the Middle East from the early 1970s until 1993. He was Chairman of the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence and the Select Committee to Investigate Covert Arms Transactions with Iran. Also a leading figure on economic policy and congressional organization, he served as Chair of the Joint Economic Committee as well as the Joint Committee on the Organization of Congress, and was a member of the House Standards of Official Conduct Committee. In his home state of Indiana, Mr. Hamilton worked hard to improve education, job training, and infrastructure. Currently, Mr. Hamilton serves as Director of the Center on Congress at Indiana University, which seeks to educate citizens on the importance of Congress and on how Congress operates within our government. Mr. Hamilton remains an important and active voice on matters of international relations and American national security. He served as a Commissioner on the United States Commission on National Security in the 21st Century (better known as the Hart-Rudman Commission), was Co-Chair with former Senator Howard Baker of the Baker-Hamilton Commission to Investigate Certain Security Issues at Los Alamos, and was Vice-Chairman of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (the 9/11 Commission), which issued its report in July 2004. He is currently a member of the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board and the President’s Homeland Security Advisory Council, as well as the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Advisory Board. Born in Daytona Beach, Florida, Mr. Hamilton relocated with his family to Tennessee and then to Evansville, Indiana. Mr. Hamilton is a graduate of DePauw University and the Indiana University School of Law, and studied for a year at Goethe University in Germany. Before his election to Congress, he practiced law in Chicago and in Columbus, Indiana. A former high school and college basketball star, he has been inducted into the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame. Mr. Hamilton’s distinguished service in government has been honored through numerous awards in public service and human rights as well as honorary degrees. He is the author of A Creative Tension—The Foreign Policy Roles of the President and Congress (2002) and How Congress Works and Why You Should Care (2004), and the coauthor of Without Precedent: The Inside Story of the 9/11 Commission (2006). Lee and his wife, the former Nancy Ann Nelson, have three children—Tracy Lynn Souza, Deborah Hamilton Kremer, and Douglas Nelson Hamilton—and five grandchildren: Christina, Maria, McLouis and Patricia Souza and Lina Ying Kremer.

|