|

by Kari Lydersen

Special to The

Washington Post

Sunday, May 15, 2005; Page N05

|

CHICAGO Artist Michael Hernandez de Luna pushes the

envelope.

Here's what he does: He makes fake stamps,

puts them on envelopes and drops the envelopes in the mail. One

stamp features an image of President Bush's face between spread

buttocks cheeks. Another showed a stained blue dress labeled

"Property of Monica Lewinsky." A third showed obese fast-food-fed

Barbie dolls.

About 40 percent of the time, according to

Hernandez de Luna, the Postal Service cancels the stamps and

delivers the mail.

Why, exactly, does he do this? He says it's a

way to get people to take a fresh look at the culture that

surrounds them.

"My environment is my collaborator," he says

during an interview in his cluttered studio in Chicago's Pilsen

neighborhood, where many Latino artists live. "I've decided to

just take what people are feeding me and go over the top. People

are getting spoon-fed this mush of media and pop culture and being

told: It's okay, just eat it. It's not okay. That's what I'm

saying. I'm not being anti-American; I'm just being a caring

person by telling the truth."

Hernandez de Luna's work has caught the eye

of the federal government. His last run-in was in April, when the

Secret Service visited a show he curated at Columbia College in

Chicago in which artists from 11 countries created stamps to

portray their definition of "evil." One of the images, by

Chicagoan Al Brandtner, showed the president with a gun to his

head and the words "Patriot Act."

Hernandez de Luna was fired from his job as a

baggage handler for American Eagle airlines several days after a

story about the incident appeared in the Chicago Sun-Times. A

picture accompanying the article showed Hernandez de Luna in his

American Eagle uniform.

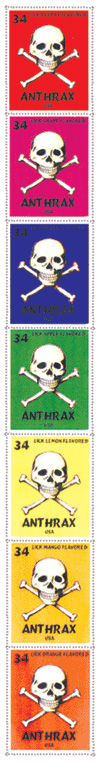

Federal authorities also launched an

investigation into his work in October 2001 after he mailed a

stamp that featured the word "anthrax" and a skull and crossbones

on a bright yellow background. That stamp caused the main post

office in Chicago to shut down for several hours. The Postal

Service sent him a postcard announcing an investigation.

"He straddles the line between artist,

activist and criminal," says Diane Barber, visual arts director of

the DiverseWorks gallery in Houston, where Hernandez de

|

Luna's work is part of a show called "Thought

Crimes."

"When I watch people walking through the exhibit,

they really spend a lot of time with his work, engage with it, talk

about it. People come up to me and say: 'Thank God you're showing

this. We need to see more things like this.' I think people are hungry

for some kind of counter-dialogue."

Hernandez de Luna, 48, graduated from the School

of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1983. His philatelic fascination

started four years later when he bought a collection of vintage U.S.

stamps in Iowa City. He took up stamp collecting in Germany, where he

worked for a company making visual and advertising materials for the

U.S. Army, and played in a garage rock band that specialized in Hank

Williams covers.

He never lost his fascination with stamps. When

he returned to his native Chicago in 1994, he even bought a 1976

Postal Service Jeep. About that time, he made his first fake stamps

with fellow Chicago artist Michael Thompson, who had started creating

his own stamps several years earlier. In 2000 the two published a book

documenting fake stamps they had sent through the mail.

Hernandez de Luna creates the stamps on a computer. The

paper he prints them on is perforated with a century-old pedal contraption

he found in a thrift store. He collects old envelopes from specialty

stores to complement the stamps. For example, a stamp of a marijuana leaf

was mailed on a 1924 envelope from the Department of Agriculture. Stamps

referring to priest sex abuse were sent on old envelopes from Boys Town

and various churches. A stamp featuring Ted Kaczynski was mailed on a

Postal Service envelope. A Bill Clinton stamp is on a copy of a White

House envelope.

He usually sends the letters to himself or to

galleries where he is exhibiting. Sometimes they arrive with messages like

"this is a fraudulent stamp" or "this is blasphemy" scrawled on them,

presumably by postal workers. Most of them are hand-canceled, meaning that

workers got a close look at the stamp and sent it through the mail anyway.

"That makes them a participant in the art," he says.

Hernandez de Luna says he is part of an international

"mail art" tradition.

One of the first fake stamps to gain attention was

French artist Yves Klein's monochrome blue, used to mail out thousands of

invitations to exhibits in the '50s. American Robert Watts, a '60s artist,

is also a patriarch of fake stamps. A number of artists currently produce

fake stamps, but Hernandez de Luna is one of the few mailing them.

Lynne Warren, curator of the Museum of Contemporary

Art in Chicago, where Hernandez de Luna's work was shown in 2003, says he

is part of the heritage of Fluxus, a radical art movement that flourished

in Europe and the United States in the 1960s in the hands of people like

Joseph Beuys and Yoko Ono. It rejected traditional art objects and

promoted happenings and other kinds of artmaking that went outside the

bounds of galleries and disturbed the status quo. "They were," Warren

says, "a very subversive lot who wanted to get art more directly to the

people."

Hernandez de Luna says the provocative content of his

stamps is appreciated, especially in the post-9/11 world of heightened

security. Many of his stamps lampoon the Republican administration, but he

also attacks high-profile Democrats, featuring references to Bill

Clinton's infidelity and Jesse Jackson's out-of-wedlock child.

"Anyone who does something shameful and deceiving,

who preaches moral greatness and then screws up, they deserve to be on a

stamp," he says. "Politicians are easy targets. And I have a real dislike

for the Catholic Church -- I was raised Catholic -- what they teach and

what they hide."

He "left the pope alone for a few years" at the

request of his mother, "a real old-fashioned Mexican woman."

A stamp that has drawn complaints shows a traditional

image of Jesus and Mary turned on its side in a sexually suggestive way.

Hernandez de Luna sees his work as a way to bring

levity to contemporary political and social issues, as in the stamps that

advertised anthrax in orange, lemon-lime and grape flavors.

"I made the fruit anthrax stamp in reaction to how

the media was so overrun with the anthrax scare," he says.

That stamp and the ensuing federal inquiry caused the

cancellation of a 2002 show of "Sinister Plants of North America" that

Hernandez de Luna and Thompson had been commissioned to do at the Peggy

Notebaert Nature Museum in Chicago.

Despite his scrapes, the FBI's Chicago office said

there is no ongoing investigation of Hernandez de Luna's work. Secret

Service spokesman Lorie Lewis said the inquiry into the Columbia College

exhibit has been completed, with no art confiscated and no one charged. A

spokeswoman for the Postal Service said she couldn't comment on whether it

is conducting an investigation but was familiar with his history. The

Postal Service issued cease-and-desist letters in 1997 and 1998.

"We respect artistic freedom, but we also have a

responsibility to look into exhibits or statements when necessary," she

said.

Hernandez de Luna has never been charged or arrested

in connection with his art. With recent works including an image of a

plane flying into the Sears Tower and "the Hamas baby bomber," Hernandez

de Luna thinks he may draw more scrutiny from authorities. It's a risk

he's willing to take.

"Everything has a consequence," he says. "If you get

in a love affair, that will have a consequence. If you do something to

provoke, as an artist that's our mission."

He says if he went to jail for his art, he could

accept that.

"If I can just get someone to really think about

what's going on in our world, I'm happy."

Return to Table of Contents |